Yellowstone’s Kelly Reilly may have won herself a global fanbase as Beth Dutton but not everyone may realise this isn’t actually her real name. Yellowstone star...

Legendary actress Ann-Margret made quite a name for herself in Hollywood through several films during the early 1960s. This includes Bye Bye Birdie, where she was...

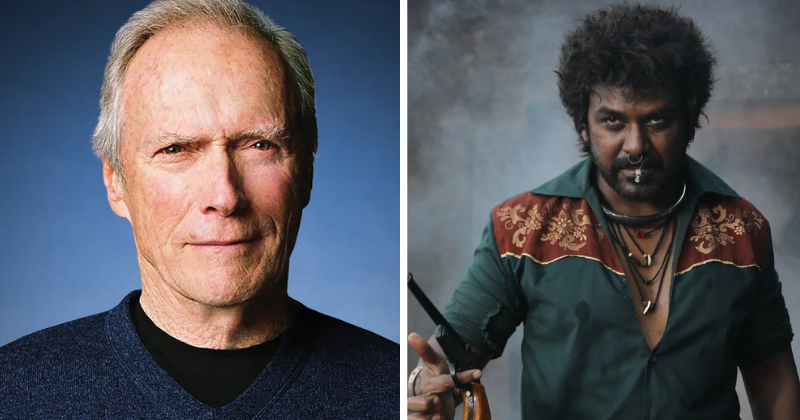

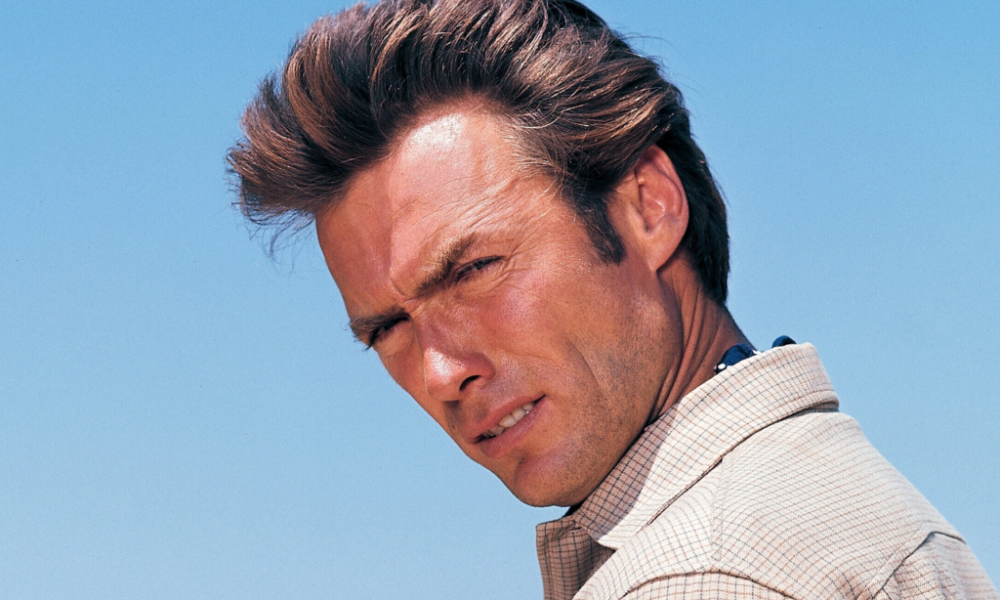

Karthik Subbaraj is overjoyed He took to Twitter to write, “Wow! Feeling So Surreal! The Legend Clint Eastwood is AWARE of Jigarthanda Double X and gonna...

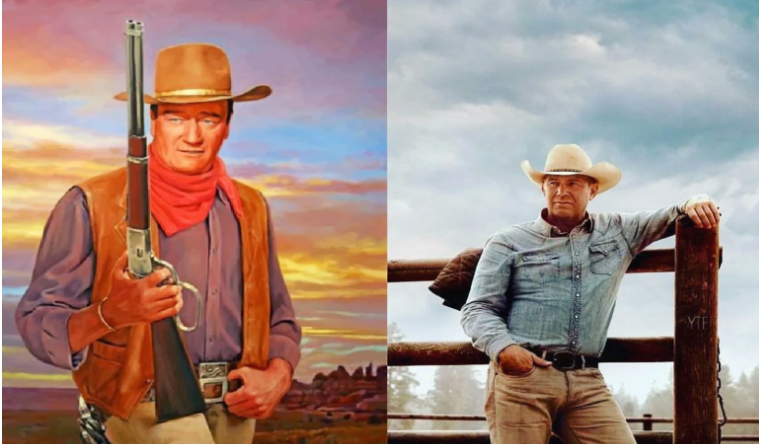

JOHN WAYNE FURIOUSLY REJECTED an offer from Steven Spielberg, branding his film “drivel.” Yet many, including the Western star’s wife Pilar, believe his actions were rooted...

1. Bigg Boss 17: Munawar Faruqui’s Ex-Girlfriend Ayesha Khan To Enter The Show On Weekend Ka Vaar Twitter The comedian is so far one of the best...

Will there ever be another Hollywood cowboy quite like John Wayne? These Yellowstone fans think Kevin Costner is the only to come close. Right off the...

Kartik Subbaraj’s Jigarthanda Double X grabs Clint Eastwood’s attention, Hollywood icon plans to watch soon. (Photo: Instagram) New Delhi: Kartik Subbaraj is overjoyed after Clint Eastwood...

We all remember John Wayne for being the honorable, heroic cowboy— yet The Duke was not without a temper. While filming his 1970 Western film, Chisum,...

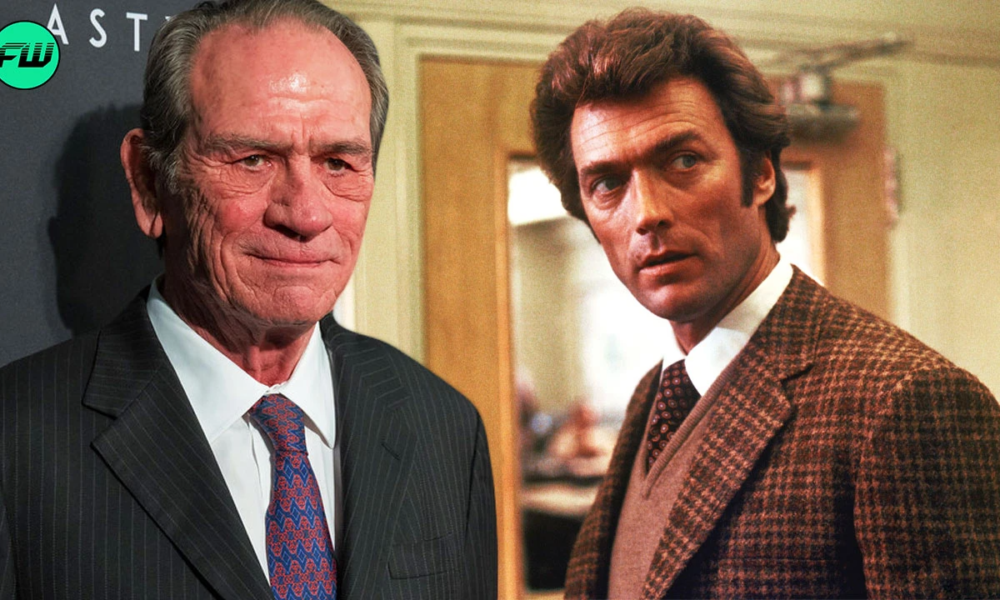

Tommy Lee Jones surprised everyone when he appeared in the role of Agent K in Men in Black. His appearance in a comedy flick was unexpected and was...

Actor John Wayne, known as The Duke by many dads and cowboy movie lovers, was a Hollywood and American icon. His western movies, such as The...