John Wayne did establish himself as one of the greatest actors ever in Western films. But did you know that he invented a punch? The venerable...

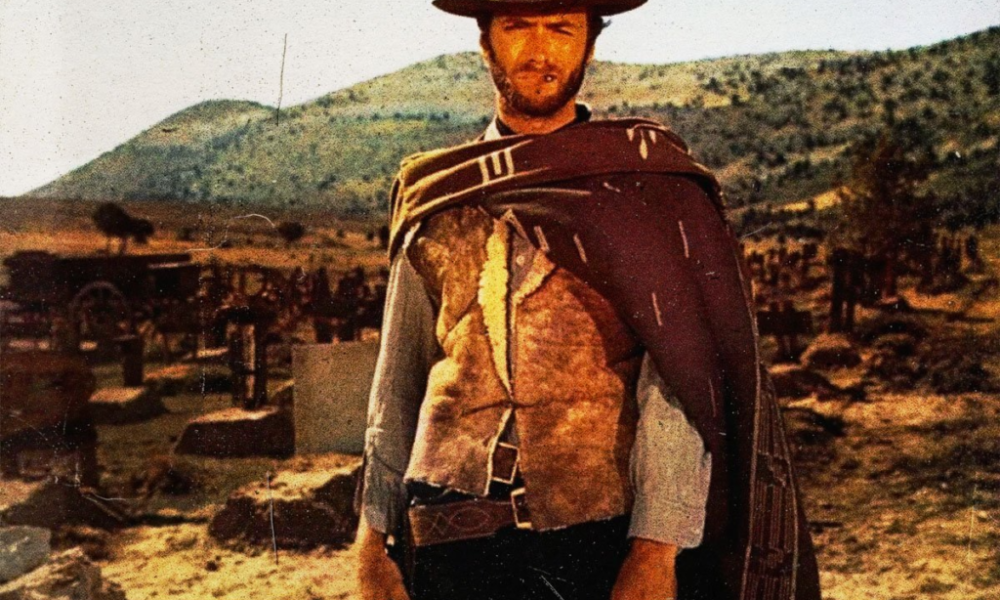

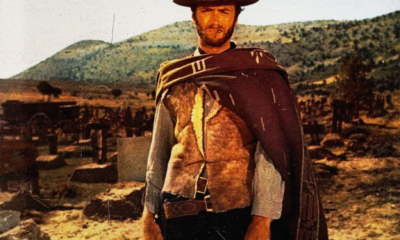

Clint Eastwood has been known around the world as a veteran director beyond all means. Eastwood, however, started his journey as an actor portraying several iconic...

Some of television’s most iconic western stars came together in the 1990s giving fans the best beer commercials ever made. It’s a throwback to some of...

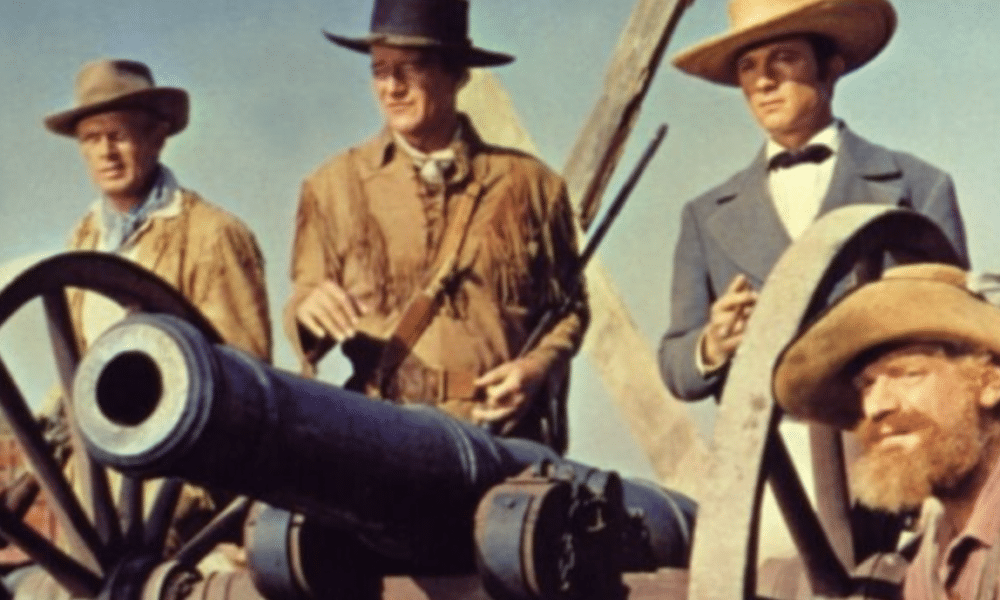

Hollywood’s most iconic cowboy, John Wayne, gave the mythic battle at The Alamo a modern presence with his 1960 film. “The Alamo,” shot in Brackettville, Texas was...

Some stars of Hollywood cinema are indelibly linked to American culture, with the likes of John Wayne, James Stewart, Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks having made...

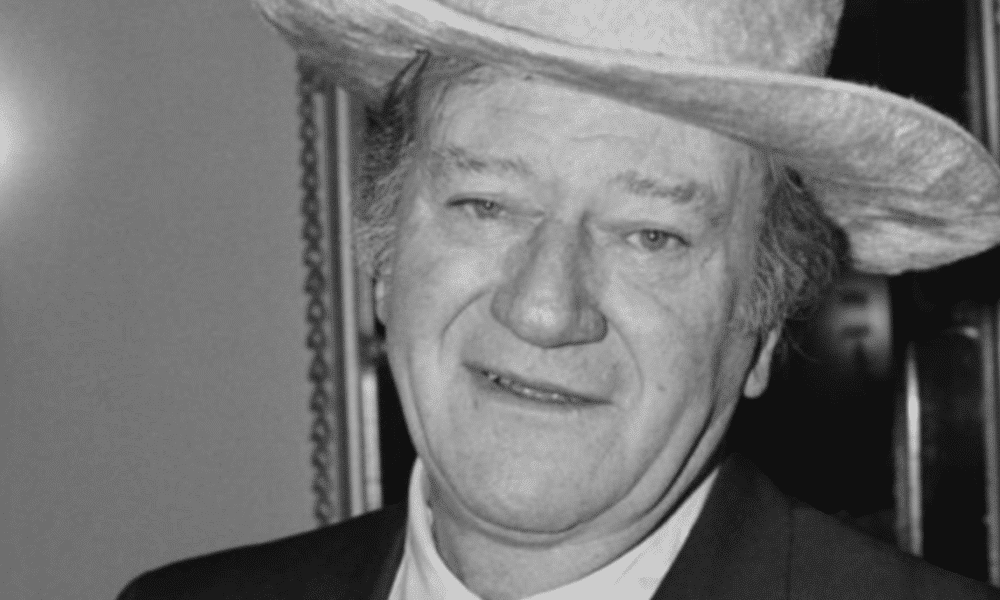

Although he is known for his more serious, western film roles, John Wayne did have a fun side, this includes him dressing up as an Easter...

Per Deadline, Simmons has been tapped to play a juror in Clint Eastwood’s upcoming courtroom thriller. He’s joining an ensemble cast that includes Nicholas Hoult, Toni Collette,...

Two of the biggest Western movie stars in the history of cinema are undeniably Clint Eastwood and John Wayne. John Wayne brought close to 200 movies...

Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More, and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly combine to form what’s become known as one of the greatest...

He has over 180 film and TV roles credited under his name, but there was only one film that American western movie icon John Wayne would return to...