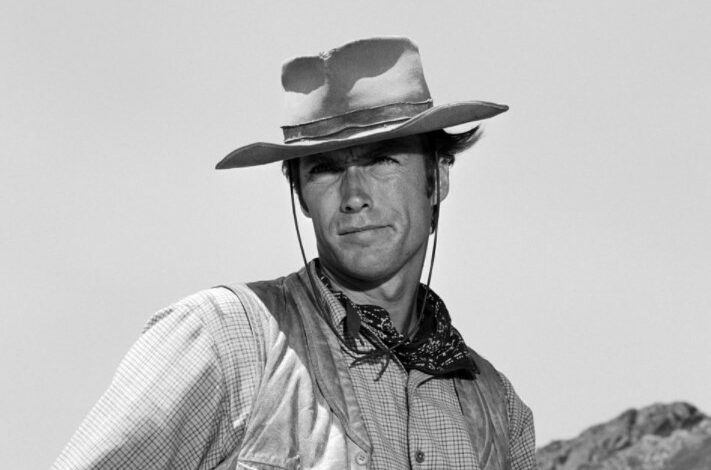

John Wayne

JOHN WAYNE IS MORE THAN A COWBJOHN WAYNE IS MORE THAN A COWBOYOY

John Wayne

The Legend Lives On: John Wayne is Still Alive!

John Wayne

Why John Wayne Turned Down the Chance to Work With Clint Eastwood

John Wayne

Ann-Margret Refused to Call John Wayne ‘Duke’ While Introducing 1 of His Movies

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoJohn Wayne’s son speaks on military service, Hollywood life and his dad, ‘The Duke’ – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago40 Legendary John Wayne Quotes – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoNew biography reveals the real John Wayne – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoWhy one POPULAR ACTOR was FIRED from THE SONS OF KATIE ELDER and lost his career as a result! – Old western – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoRio Lobo (1970) marked the last collaboration between John Wayne and Howard Hawks. – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoHow Maureen O’Hara Broke Her Hand During Iconic Scene With John Wayne – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoJohn Wayne and the ‘Bonanza’ Cast Appeared in This Epic Coors Light Commercial – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoDid John Wayne really have a good time filming 1972’s The Cowboys? – My Blog

John Wayne | Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

John Wayne | Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images