The 1993 film is among Eastwood’s best directorial efforts.

At 91 years old, Clint Eastwood continues to be one of Hollywood’s most prolific directors. Eastwood often puts projects together quickly; Richard Jewell began filming in June and hit its December release date, and less than a year later he was back behind and in front of the camera for his latest feature Cry Macho. While Eastwood has teased that Cry Macho may be his closing chapter, it’s anyone’s guess if he’ll follow through with that promise or find another story that sparks his interest.

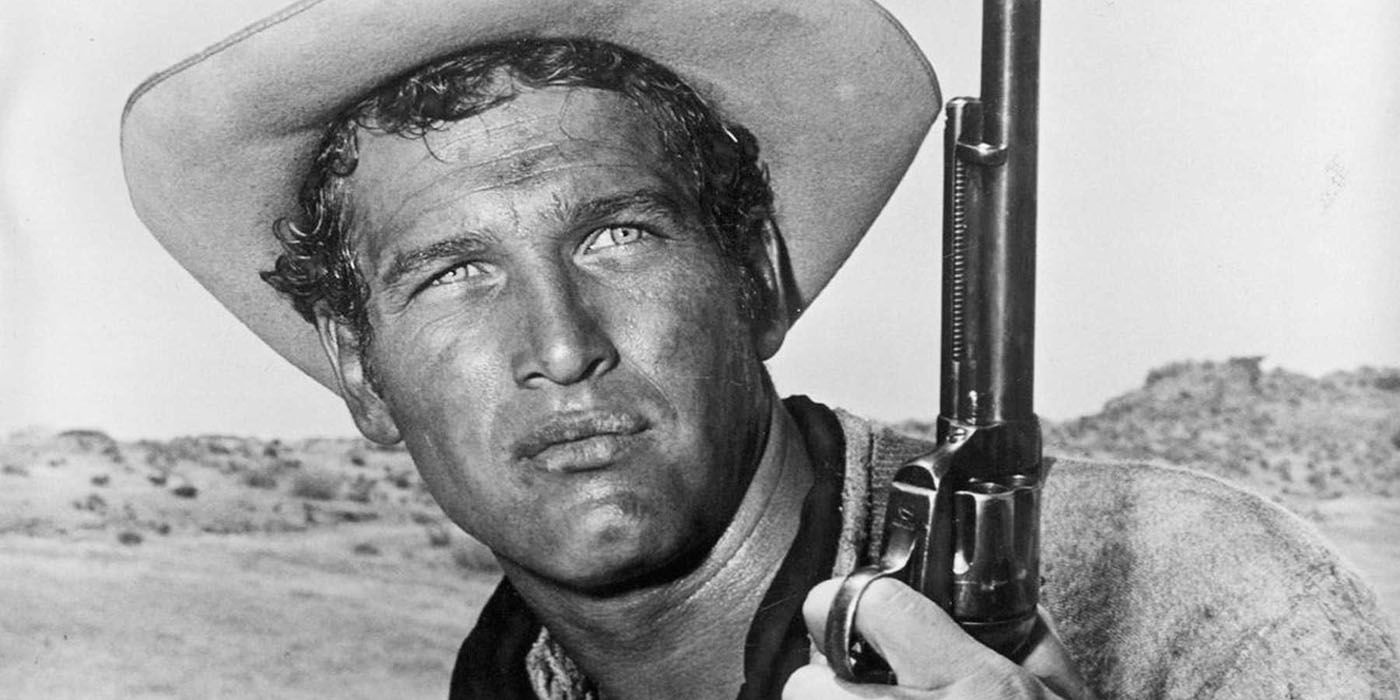

Compared to his other work, 1993’s A Perfect World is somewhat of an anomaly. Eastwood has nearly forty directorial credits to his name and gravitates towards westerns, action films, and thrillers. Based on the premise alone, A Perfect World sounds like it’s right up Eastwood’s alley. Set in Texas in 1963, the film follows escaped convict Butch Haynes (Kevin Costner), who takes an eight-year-old child named Phillip (T. J. Lowther) hostage while fleeing authorities.

Regret and destiny are themes Eastwood frequently explores, yet A Perfect World is among the most tragic and surprisingly unsentimental films of his career. Phillip isn’t utilized to soften the heart of the gruff Butch, nor is Phillip empowered by the dangerous experience. It’s a film about trauma that doesn’t heal; Phillip and Butch are able to momentarily bond while discussing their pasts, but their realities don’t change as a result.

As Butch travels with the boy towards an escape route in New Mexico, he’s steadily impressed by his captive’s inventiveness. Phillip steals a ghost costume, but it’s not framed as a cutesy moment. Rather, he’s shown a disregard for civility reminiscent of the man he just watched kill his own partner.

Phillip was raised in a Jehovah’s Witness community by his mother and sisters, and Butch gives him a broader worldview. His naivete isn’t exaggerated; there are more blatant aspects of childhood that Butch is surprised to learn Phillip knows nothing about (such as Christmas or Halloween celebrations), but he’s also secluded from developing self-respect. When Hayne encourages Phillip to have confidence after the boy reveals he’s been bullied, it’s not positioned as an out-of-character moment of kindness on Butch’s behalf. The words of encouragement come as a surprise, and the scene is more tragic in revealing Phillip’s self-loathing than they are a charming moment of bonding.

Butch’s growing interest in Phillip’s development are strengthened as he reveals his own troubled childhood. Fleeing his violent father, Butch had already developed a reputation by the time he was a teenager and served a full sentence after being denied juvenile prison. Butch’s supportive words of Phillip are tragically ironic; they’re an attempt at replicating a father-son relationship he never had, even if he knows it isn’t sustainable.

While Phillip takes Butch’s lessons about right and wrong to heart, he also learns that his new father figure often doesn’t follow his own rules. As the pair hides at a ranch New Mexico, Butch becomes angered witnessing the violent outbursts that the owner Mack (Wayne Dehart) inflicts upon his wife. Butch threatens to kill him, and Phillip is forced to evaluate the situation in a split second. Is Butch justified, and would Mack’s death even resolve the situation? These aren’t questions an eight-year-old should have to consider, let alone bear responsibility for, but in the tense face off, Phillip is forced to be the voice of reason.

Eastwood casts himself as Texas Ranger Red Garnett, who aims to capture Butch alive before he sparks a conflict with other pursuing authorities. Garnett’s motivation in aprehending Butch is personal, as its revealed that he was the arresting officer that detained Garnett in his youth. Butch is unaware of the connection, but its a decision that haunts Garnett. While he thought that forcing Butch to see the consequences of his actions would’ve spared him of his abusive father, he realizes that it only hardened Butch’s outlook.

Eastwood frequently casts himself in the lead, but he’s equally effective in a supporting role. Garnett is far different than a character like Unforgiven’s Will Munny, as he’s not an evil man trying to redeem a life of hatred, but rather a career lawman regretting a misconstrued attempt at giving Butch a way out. Eastwood is terrific playing internalized guilt, as Garnett only gradually reveals his motivations to criminologist Sally Gerber (Laura Dern). While the film builds towards their confrontation, they don’t share words; Butch never learns of the man who sealed his fate, and Garnett never gets the chance to voice his apology.

Eastwood is no stranger to long runtimes, but A Perfect World’s 138 minutes don’t feel excessive. The suspenseful sequences are realistic; when Butch’s partner Terry Pugh (Keith Szarabajka) threatens to kill him, they discuss their options over an extended conversation. The two aggressive men have reason enough to hate each other, as they only escaped together out of necessity, but both understand the value in mapping an escape together. That Terry’s death only comes after he threatens Phillip is a great character building moment for Butch; he’s willing to risk his own future to protect Phillip in the film’s first true act of selflessness.

Although tension steadily mounts as Garnett follows Butch’s trail, the climax is more of an inevitability than it is the conclusion of a relentless chase. Butch’s death comes through another mischaracterized act of kindness; choosing to spend a few fleeting moments with Phillip, a simple gift is misinterpreted as a weapon by a triggerhappy sniper. In this moment all the characters see their “perfect world” slip away; Garnett loses his chance to confess to Butch, Phillip is doomed to return to his religious upbrining, and Butch loses his life after showing his benevolence. While he’s known for his lack of storyboarding and minimal camera setups, Eastwood’s meticulous approach to conflict in A Perfect World’s tragedy makes it more effective.

Eastwood is known for his hypermasculine characters, but A Perfect World is perhaps his best film about masculinity, as its trio of traumatized men are all punished for showing sensitivity. Eastwood’s films are frequently under fire for their political baggage, but A Perfect World doesn’t lionize its characters or offer an easy solution. It presents a slice of reality, and the flawed characters forced to inhabit it.

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.