Watching movies you loved as a kid can reveal things you missed, offering fresh insight as you catch new details, including the occasional inconsistency or editing mistake. Revisiting Dirty Dancing, a film cherished since its release in 1987, reveals just how much effort went into creating this iconic story of love and dance. Even though it remains a fan favorite for its music, memorable characters, and classic storyline, some bloopers and continuity errors slipped through the cracks. Let’s look into these surprising goofs in this beloved film, from unnoticed edits to interesting details involving the characters.

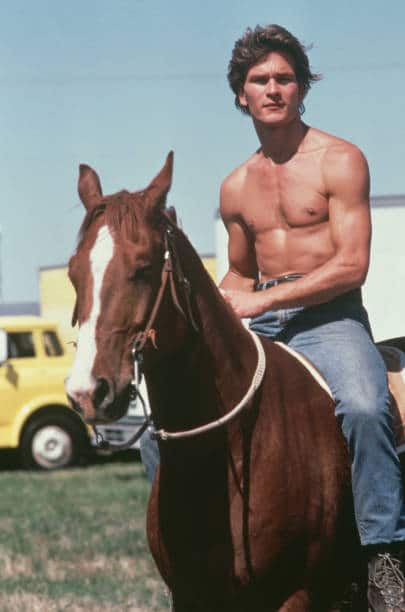

Revisiting classic movies like Dirty Dancing evokes nostalgia. The film, which captures the spirit of love and rebellion, has managed to stay relevant for decades. Even years after its release, scenes like Johnny lifting Baby remain unforgettable, accompanied by hits like “I’ve Had the Time of My Life” and “Hungry Eyes.” With Patrick Swayze and Jennifer Grey’s characters displaying undeniable chemistry, the film presents an iconic blend of romance, dance, and drama. But like all art, Dirty Dancing wasn’t crafted perfectly. Small mistakes and continuity slips add a unique charm, though they also highlight some surprising production oversights.

One of the most famous scenes involves the charismatic Johnny Castle, played by Patrick Swayze, performing his unforgettable final dance. As he leads Baby onto the dance floor, viewers who pay close attention might notice his hair mysteriously changing from wet to dry between takes. In one moment, he’s glistening with sweat; in another, his hair is mysteriously dry. This change is almost as if the passionate dance routine has its own hidden magic! This editing inconsistency may seem small, but for eagle-eyed viewers, it’s a curious flaw in an otherwise smooth performance.

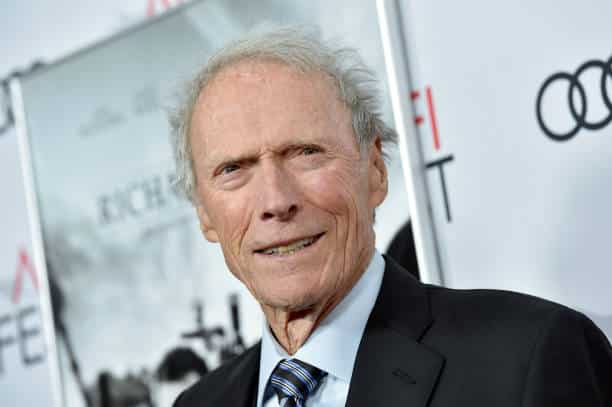

Patrick Swayze smiles for camera.

Another humorous continuity issue occurs when Johnn and Baby finish their dance. Johnny, in his leather jacket, escorts Baby across the dance floor, but in a following shot, the pair reappears at the dance floor’s center, where they had just finished their routine. It’s an unusual moment, as if the two characters moved back and forth without explanation. While these lapses don’t detract from the magic of the scene, they do offer fans a fun opportunity to catch the production team’s small slip-ups.

Speaking of the iconic leather jacket, it makes yet another surprising appearance. In one scene, Johnny dramatically removes his jacket before the dance, tossing it aside with flair. However, in a follow-up angle, he’s seen taking it off again as though it magically reappeared. This repetition may have been an unintentional error, but it’s a minor oversight that stands out when you watch closely.

An even subtler inconsistency involves one of Baby’s most famous lines, delivered during a nervous moment when she first interacts with Johnny. She awkwardly says, “I carried a watermelon,” in response to his questioning gaze. Embarrassed, she mouths the line to herself as if questioning why she said it. Moments later, however, Baby says the line out loud once more in a different shot, creating a duplicate of her internal cringe. For those who catch it, it’s an amusing little blunder that adds to the charm of her awkward interaction with Johnny.

One of the more amusing aspects of the film involves the real-life interactions between Patrick Swayze and Jennifer Grey. Their chemistry is palpable on screen, but it wasn’t always smooth behind the scenes. There were times when their personalities clashed, leading to moments of frustration during filming. A scene where Swayze’s character runs his hand down Grey’s arm captures a genuine reaction: the visible frustration as she repeatedly missteps was unscripted, as Swayze reportedly became irritated by the delays. In his autobiography, Swayze revealed how their different approaches led to friction. He described Grey as having a tendency to laugh or become emotional during takes, causing occasional delays and requiring patience on his part. However, their dynamic created a uniquely authentic connection, giving their characters’ chemistry an extra layer of realism.

Another well-loved part of the film is the climactic lift scene, where Johnny raises Baby high in the air. Contrary to what some might think, Jennifer Grey was terrified of the lift and insisted on performing it only once. Her anxiety about the scene actually added a level of intensity that made it even more memorable. That single take became an iconic moment that fans continue to celebrate. Her genuine fear gave the lift an authentic edge, contributing to its emotional impact.

As the film progresses, one last continuity error sneaks into a scene involving Johnny’s belt. Toward the end, Johnny defends Penny by confronting Robbie, the man responsible for her pregnancy. During their fight, Johnny’s belt appears to be securely fastened. However, in a subsequent shot, the belt looks mysteriously undone, only to be fastened again moments later. Though minor, these small wardrobe malfunctions subtly disrupt the flow, creating amusing Easter eggs for observant viewers.

While these mistakes and continuity issues don’t detract from the movie’s enjoyment, they offer fans of Dirty Dancing something extra to discuss and laugh about. Recognizing these little bloopers adds a layer of charm to an already beloved film, reminding us that even cherished classics aren’t perfect. In a way, these imperfections make the film even more endearing because they reveal the human side of the production process. Movies, much like any creative work, often undergo countless takes, edits, and tweaks, and it’s almost inevitable for some details to escape notice.

Despite these small errors, Dirty Dancing has endured as a cultural phenomenon. Its memorable soundtrack, combined with the unique charisma of its leads, ensures it continues to inspire new generations of fans. Watching the film again, knowing about these behind-the-scenes details, only adds depth to the experience. It’s a movie that, even with its slip-ups, has the rare ability to create a lasting emotional impact. The characters’ journey, the unforgettable music, and the joyous celebration of dance remind audiences of the magic that storytelling brings, even if it’s not flawless.

Every time we return to Dirty Dancing, we discover something new—whether it’s a continuity mistake or an extra beat of chemistry between Johnny and Baby. It’s a testament to the film’s charm that fans continue to embrace it, imperfections and all. Just as the characters grow and learn in the story, viewers find fresh details to enjoy with every rewatch. These little mishaps offer fans a fun opportunity to appreciate the quirks that make the film feel like an old friend, full of charm and a bit rough around the edges, just like life itself.

PROC. BY MOVIES

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago