If I’m being honest, when choosing to settle down with a good old western, I usually choose to pick the more stylised, epic works of Sergio...

Robert Duvall currently has 3 films in production as he turns 91 this week. The actor once fired up fellow western actor John Wayne so much...

Martin Scorsese helmed a lot of timeless films during the ‘80s, such as After Hours, The Last Temptation of Christ, and The Color of Money. However, the director also rejected...

John Wayne had to play the pot-bellied, one-eyed Westerner before the Academy would consider him to be an actor worthy of an Oscar. In his career...

THE BIG PICTURE Clint Eastwood’s The Outlaw Josey Wales is a Western film that delves into the harsh realities of violence and warfare. Eastwood labels the film as...

Mother’s Day is an opportunity to celebrate and honor the mother of a family, as well as motherhood and maternal bonds at large. However, not everyone...

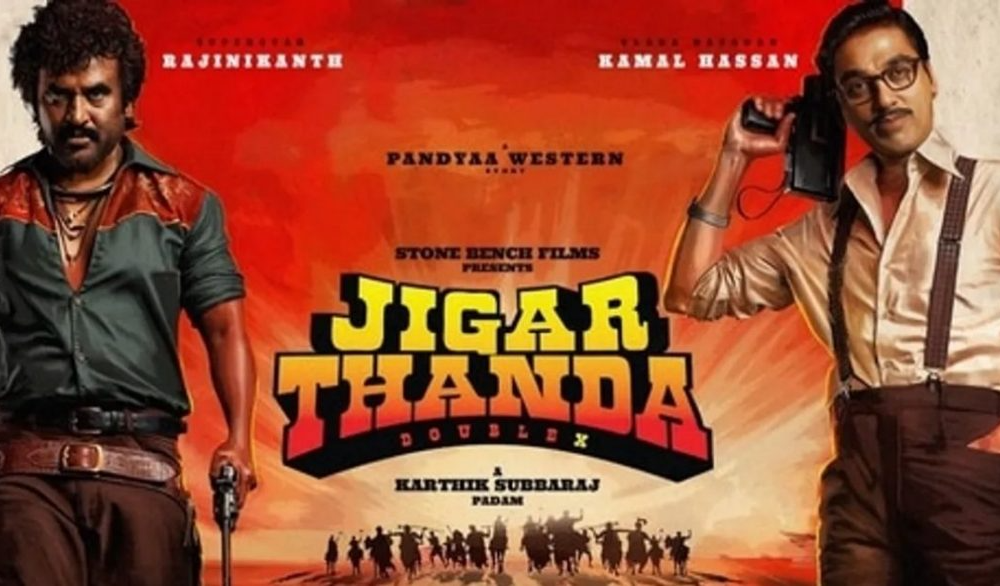

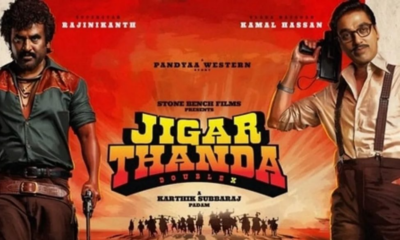

AS the final reels of Karthik Subbaraj’s Jigarthanda Double X flicker by, Raghavendra Lawrence, the South Indian choreographer-turned-actor, delivers a speech as ‘Alliyan Caesar’ that resonates with the raw...

Ron Howard was only in his early 20s when he encountered John Wayne and learned how to work with one of the most intimidating men in...

SUMMARY Eastwood’s iconic Western movie quotes showcase the uncertain nature of life in the Wild West and the peace that comes with having money. Eastwood’s portrayal...

Munoz, Melinda Wayne John Wayne Cancer Foundation Advocate and Supporter Passes Away Melinda Wayne Munoz has died, and the cause of death is unknown. Melinda Wayne Munoz, John...