The words are spoken by none other than Charles Bronson, perhaps the last actor in the world one expects to say these words. The film is the 1975 Western adventure Breakheart Pass, directed by Tom Gries, and no, Bronson is not playing either Jesus Christ or Mahatma Gandhi in the film, though his initial actions in the film might raise suspicions to that account – Bronson’s character, John Deakin, is kicked, slapped around and then cuffed, tied and relegated to the floor of a train, with nary a protest or hint of violence from the macho star, who just keep repeating that he is non-violent. Bronson films are usually filled with violence of every kind, and Breakheart Pass is no exception; the film has action, adventure, mystery, and yes violence too, but it’s still one of those rarest of rare films: a PG rated Charles Bronson action thriller from the 1970s, and that too just a year after Bronson himself took violence in movies to a new level with his vigilante thriller Death Wish. So, the much toned down nature of Breakheart Pass is truly surprising. The film concentrates on building suspense, rather than in random acts of violence.

The film is adapted from an Alistair MacLean novel and this is one of the most faithful MacLean adaptations, maybe because the author himself wrote the screenplay. MacLean usually writes either suspenseful action thrillers set during WWII, or more contemporary twisty thrillers, Breakheart Pass is the lone MacLean novel set in the Old-west, and though every Maclean novel has an element of mystery involved in it, here, he makes the mystery the main aspect of the film. The film borrows equally from John Ford’s iconic Stagecoach(1939) as it does from Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express, which was made into a very popular movie by director Sidney Lumet in 1974.

The plot of the film goes something like this: it’s the 1870’s. A special train is being sent to Fort Humboldt, a frontier outpost, with medical supplies and a relief force to combat the diphtheria that has broken out there. The territorial Governor Fairchild (Richard Crenna) is taking personal charge of the operation, the troops are commanded by cavalry Major Claremont(Ed Lauter). Along for the ride is a U.S. Marshal, Pearce (Ben Johnson), Doctor Molyneux(David Huddleston), Fort Humboldt’s Commanding officer’s daughter, Marica Scoville (Jill Ireland) and Reverend Peabody(Bill McKinney). The train engineer is played by Roy Jenson and the conductor O’Brien is Charles Durning. Governor Fairchild travels in style in a private car with a cook, Carlos (Archie Moore), and a server (Victor Mohica). On the way, they pickup a wanted criminal, John Deakin (Charles Bronson). As the Train makes it journey thought the Rocky mountains, the passengers start getting killed one by one. First, a few of the Major’s soldiers goes missing; then the doctor is found dead; after that, the fireman is thrown from the engine car while the train is crossing a steep wooden bridge. Obviously, there is a killer or a group of killers on the train. It soon become obvious that none of the passengers- including Deakin – are what they appear to be, and neither is the purpose of the journey as clean cut as delivering medical supplies. Deakin turns out to be an undercover government agent (this is revealed pretty early in the film) and it’s up to him to uncover the mystery, which involves corrupt government officials, angry native tribes, illegal arms sales and gold smuggling.

As it is obvious from the plot synopsis, the film boasts of a great star cast , and one of the pleasures of the movie is seeing them play off each other, especially as the mystery deepens and it is left to the audience to guess who are the good guys and who are the bad guys. Bronson, Johnson, Lauter, all veterans of Westerns, does great work here, with Crenna, Durning and others lending great support. Jill Ireland, Bronson’s wife in real life and his regular screen partner, lends her feminine charms to this otherwise masculine drama. The film borrows the basic template from Stagecoach – a group of disparate American characters travelling through hostile Indian territory; only here, the Coach is replaced by a smoky train. Also, Bronson’s John Deakin intrudes into their journey in the same way as outlaw, Ringo Kid (John Wayne) does in Stagecoach; Both Deakin and Kid turns out, not to be the bad guys their reputation suggests, and in the end they emerges as the heroes who save the day. The buildup of the suspense set around a train journey is very reminiscent of Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express, with Deakin becoming the Hercule Poirot surrogate; investigating the murders\disappearances and unearthing clues to the unfolding mystery. The film also borrows from Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes(1938) – another mystery thriller set on a train, with its themes of espionage and political conspiracies.

Though the film is one of the most faithful adaptations of an Alistair Maclean

novel, It does departs from the novel at several points, the most important one being that it is revealed much early in the film that Deakin is a secret service agent, as opposed to the book where it is revealed only very late. Also, in the novel, Marica is Fairchild’s niece, while it’s changed to a sort of romantic relationship in the movie; Richard Crenna portrays Fairchild as a cunning and resourceful person, while in the novel, he’s a rather stupid coward. Bronson wanted to stick close to the book regarding the revelation of Deakin’s identity, but the filmmakers changed it – much to the chagrin of Bronson – so that the last hour of the film could play as a regular Cavalry Vs. Indians Western. I feel the generic last half hour, which provides us with the typical genre pleasures – chases on horseback, shootings, confrontation with Native tribes, derailing of trains, cavalry charges etc. – is inferior to the suspenseful first hour of the film. The climax is also changed from the novel- where the story ends with a spectacular “Bridge on the river Kwai” style exploding bridge and derailing of a train. Maybe producers didn’t have enough budget to shoot that climax, so they set it around a stationary train.

Though the film concentrates more on suspense, the film still has some great action scenes choreographed by the legendary stunt coordinator Yakima Canutt. Canutt had directed the climactic gunfight in Stagecoach and the Chariot race in Ben-Hur, Breakheart Pass was his last film. Here he designed some spectacular scenes, like the one where the troop carriages are detached from the main body of the train and they crash off the rail line into a ravine. But the most memorable action sequence is the thrilling fight between Bronson and boxing champ Archie Moore on the snow covered train roof-top as the train hurtles along though the mountain pass. The scene is superbly shot by the great cinematographer Lucien Ballard – who had shot great westerns for Sam Peckinpah like The Wild Bunch (1969) . Though the film is set in Nevada, shooting was mainly done in Idaho; and Ballard showcases the beautiful landscape to the optimum. The terrific Jerry Goldsmith score complements the film; it is both rousing and ominous, befitting a suspenseful western adventure. The film is directed by Tom Gries, who started off in television and later made his film debut in the late 60’s with some well respected revisionist movies like the western Will Penny and sports drama Number One, both starring Charlton Heston. But by the mid 1970’s, he had become a very traditional filmmaker; he had made the contemporary crime thriller Breakout with Bronson earlier that year. Here, he does a very efficient job of mixing genres, keeping the narrative straightforward, without going into too many twists or turns. He realizes that, at the end of the day, this is very much an escapist Charles Bronson action\adventure movie and he strives to make it a fresh and enjoyable experience for the audience without disappointing the hardcore Bronson fans- and Gries accomplishes this very successfully.

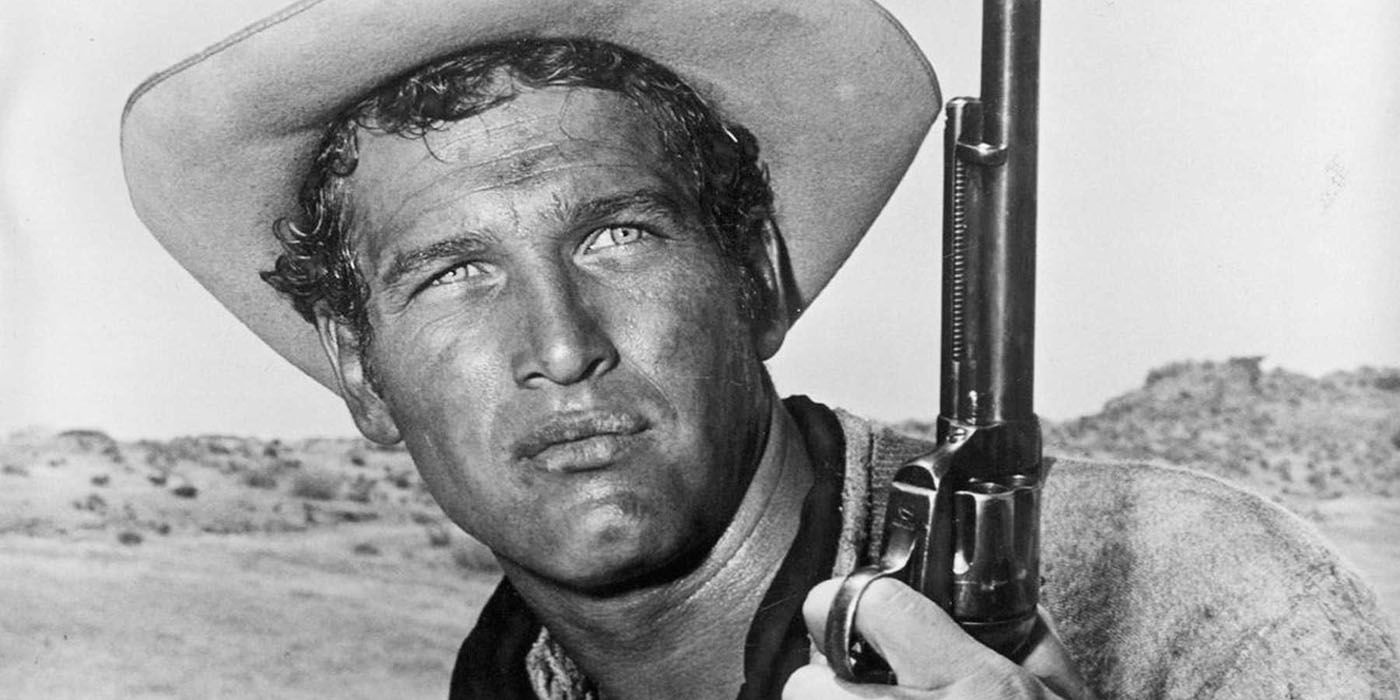

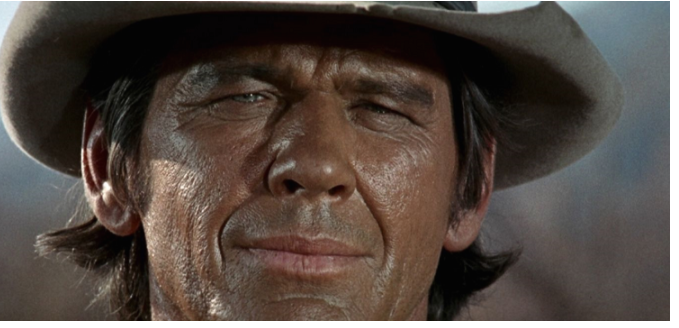

The film was made at the height of Bronson’s career. After doing supporting parts in very successful ensemble dramas like The Magnificent Seven, The Great Escape , The Dirty Dozen etc., Bronson had attained international stardom with Sergio Leone’s Once upon a time in the West. The success of Death Wish(1974) would solidify his American stardom. He was one of the highest paid actors at the time and also the most prolific; in 1975 alone he made three movies, apart from Breakheart Pass and Breakout, he also made Walter Hill’s depression era dram Hard Times. It was also a time when Bronson was trying to expand his image by doing slightly different roles (films) from his regular stone-faced avenging angels; films like Hard Times, White Buffalo, From Noon Till Three etc. were expected to broaden his audience appeal. Unfortunately, none of them, including Breakheart Pass, was commercially successful.

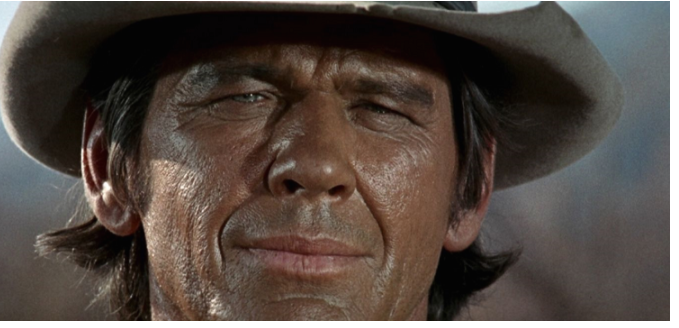

This was the reason why he never became a star of the magnitude and durability of a Clint Eastwood, and he was soon relegated to his bread and butter B action movies and countless Death Wish sequels. Bronson was 53 when he made this movie, and though his face showed the ravages of age – he was never a conventionally good looking movie star to begin with anyway – he was in superb physical shape, clearly evident from the fighting scenes in Hard Times. In this film, he is fully up to the challenges of doing difficult stunts; whether fisticuffs on the roof of the train or gunfights on the horseback. As an actor, Brosnan was a minimalist, much like Clint Eastwood, and his harsh, almost expressionless face made him perfect for playing mysterious tough guys, whether it is the avenging angel Harmonica in Once upon a time in the West or the secret service agent masquerading as an outlaw here. In that regard, Breakheart Pass is one of the best Charles Bronson films, where he is perfect.

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.