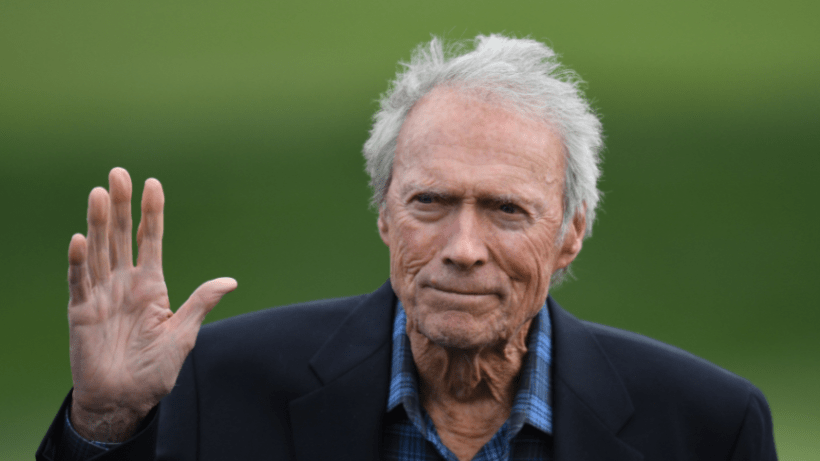

Clint Eastwood

Clint Eastwood: ”Wherever I came from, I always came out of left field

The wind groaned with a sound-studio’s boosted resonance, and halfway through a night frozen white and jagged, an outtake from a Sergeant Preston of the Yukon movie, a Rolls and a couple of big- boss BMWs discharged a small group of men at the bottom of the stairway of a private plane at Riem Airport in Munich. Luftwaffe bombing runs to Coventry or Rotterdam were called off on nights like this, but The Clint Eastwood Magical Respectability and European Accolade and Adulation Tour moved on. The Gulfstream’s jet engines rumbled, a ground-crew type pleading, in German, for an autograph was shown to the door, and the plane lifted itself into the gale, carrying the actor and director, the world’s most popular film star over the last 15 years, to England.

The tour had started in Paris in January with a retrospective at the Cinemath eque, and Eastwood’s decoration by the Ministry of Culture as a Chevalier des Arts et Lettres. Then it shifted to Munich for more of the same: the start of a retrospective at the Filmmuseum there, and, as in France, the deep, wet embrace of at least part of the country’s film intellectuals.

As enterprises go, the tour was an intriguing one, bones being consciously fitted under the flesh of Clint Eastwood’s new, public embodiment as a very important American film maker. As cultural, or political, phenomena go, it was plain fascinating. Until a couple of years ago, Eastwood, actor or director, had been consistently reviled as a cinematic caveman, a lowbrow and lunkhead credited with a single, frightening trick: his Dirty Harry cop pictures seemed to tap straight into the part of the American psyche where the nation’s brutal, simplistic and autocratic reflexes were stored. The great, foul audience, guzzling diet cola and wolfing down whole cartons of Milk Duds, had been seduced into roaring with base delight as Dirty Harry cleaned up murderers the authorities would have left free. If you paid attention to many of the critics, this was do-it-yourself justice, and pandering to redneck mindlessness. Eastwood’s approach, some Americans and Europeans insisted, was that of a potential or proto-fascist; his Dirty Harry films were deeply, truly immoral. A French writer pushed further: Eastwood was pure bully, pure bigot, America looking for a new Vietnam. Hollywood, the argument ran, had finally cloned John Wayne.

Then something changed, and the times, perhaps, caught up to Clint Eastwood. Jane Fonda did knee bends; Yves Montand began to talk like Alexander Haig. Encounter groups became a joke, Jimmy Carter told of beating off an assault by an attack rabbit, the rhetoric of the 1960’s fell through the floor, and the critics switched direction on Eastwood’s work like a crowd doing ”the wave” at a football game. Perhaps his best film, ”The Outlaw Josey Wales” – all outrage, and, most of all, fury against κıււıոɡ, brutality, and ԝаr – was made in 1976, but no matter. Suddenly, in 1985, Dirty Harry, for some, is funny, ironic, a fantasy, operatic in tone and politically prescient. ”Honkytonk Man” gets compared to ”The Grapes of Wrath” (”My God,” the actor-director says). The Eastwood acting style has evolved, adjectivally at least, from wooden to spare or economical. Someone writes that he is a feminist film director. The Guardian, the left-wing British newspaper, invites him to lecture on film, and offers a half-page explanation of his tenderness under the mysterious headline, ”A Die-Hard Liberal Behind the Magnum Image.” Uncharacteristically discreet about such political transgressions, The Guardian spares its readers news of Eastwood’s occasional telephone conversations with President Reagan, a man the newspaper treats as a knave or an ogre. Everywhere, all the good, warm, trust-words come raining down: alienated, vulnerable, sensitive, self- deprecating. Even Norman Mailer visited Eastwood for a beer and a little talk: ”He’s one of the nicest people you ever met.” ”Eastwood is an artist.” ”He has a Presidential face.” ”Maybe there is no one more American than he.”

The Gulfstream is bucking forward someplace over France, heading for Luton Airport, outside London, and Eastwood is being asked to talk a bit about respect and his new respectability, about being deemed vulnerable, generous and terribly significant, almost overnight, at age 54. He comes at answers slowly, hedging, digressing, stalling artfully until he figures out what he wants to say. A man with a good mind and a good memory, he has a knack for suspending a question, like leaving a pot at the edge of burner, before pushing it back on the fire when he is good and ready. The Munich segment, Eastwood agrees, keeping the pot well from the flame, had not really followed the ”serious philosophy” of the tour (a Wаrոеr Brothers P.R. man’s expression), but he considers it no great loss because it had degenerated amusingly. There was a Spanish countess who had gotten to interview him, asking questions about whether he wanted to act with Greta Garbo – ”Who me, I don’t have a foot fetish,” comes Eastwood’s exhausted reply – and there was a television appearance on a variety show with an M.C. described by Lennie Hirshan, Eastwood’s agent, ”as the kind of guy Dirty Harry would have ѕһot if he had the opportunity.” It could have been Joe Franklin on a Tuesday afternoon: the actor’s TV slot was between a kid who was going to see how long he could swim in an icy river and a rock group called the Kane Gang. A flack named Horst, who had been specifically told that Eastwood did not want to receive a plaque on the show (a fan-mag job, and not consistent with the new film-archives image), jimmied open a car’s trunk to make sure he got one.

The Wаrոеr Brothers’ jet descends and the conversation flattens, no clear answers at hand. A digital altimeter on the passenger-cabin bulkhead ticks down, 800, 700, 500. Nothing to see through the windows except basic black. At 400 feet, a strange nonsound, a sense of nonmotion envelops the cabin. It is as if the jet engines had been cut and the aircraft is adrift and powerless. Suddenly, the plane tilts backward, and the passengers are jolted against the backs of the seats. The Gulfstream pulls up hard and away.

A reporter on the tour, realizing that the plane had dropped to ground level and then backed off when the pilot noticed the airport was invisible, broke into a terrified sweat. When he looked around, he saw Eastwood climbing out of his seat and heading for the cockpit. He was gone quite a while, and during that time, the reporter, remembering that Eastwood as a soldier in the 1950’s had been in a plane that crash-landed off northern California, thought that if he were going to see the man at all, well, here was his ѕһot.

The plane ran through its approach again, the altimeter blinked down, and the runway lights finally broke through the black. Eastwood returned. ”Were you scared?” he was asked.

”No,” he said.

Either Eastwood was wholly bogus, a liar, which seemed unlikely, or he was answering the question about vulnerability, and explaining why so many people attach their fantasies to him, and why certain others have detested him so completely. ”I just went up to watch the pilots work,” he said. Painful as it may be to some of his new admirers, Eastwood seems to be exactly what he’s told us about himself as Dirty Harry, or Josey Wales: cool, resolved, in control, self-reliant, somehow not quite in reach. No need to read him too deeply. No need to chisel tortured ambiguity, restlessness, into the granite of the distant hero’s face. With Clint Eastwood, you get what you see, what you’ve always seen.

Up close now, bearded, Eastwood’s face has something legendary about it. Driving past the Houses of Parliament in London, someone says that there is a statue of Abraham Lincoln there, and someone else recalls a man telling Eastwood that he looks more like Lincoln these days than Dirty Harry.

The remark seems to make him uncomfortable. He says nothing. He looks out the window. Needled, kidded, treated like a third-rater for so long, respected so late, he is essentially a wary man. He finds none of Dirty Harry’s easy derision, no one-line dart, to call on to make the Lincoln talk disappear. Eastwood is condemned to saying what he thinks.

”You know,” he says after a while, ”I’d like to know what the economics of that were. I mean freeing the slaves. I’d like to know what was behind it.” HAT IS THIS JERK doing directing films we’re not going to like when we don’t even like him as an actor?” Clint Eastwood said that of himself recently, trying to sum up the prevailing critical view of his work over the last 15 years. It’s an old story. The cover of Life magazine on July 23, 1971, carried the actor’s picture and the caption, ”The world’s favorite movie star is – no kidding – Clint Eastwood.”

Mostly, Clint Eastwood has been a surprise and afterthought, even to himself. He comes from an America where it is bad form to take yourself with gravity, to sound too analytical, an America that will accept risk and loss but likes pretense as little as it likes being pushed around. In hours of talking, the phrase ”the body of my work” comes out of his mouth once, and he looks embarrassed, as if he wants it right back, so grand and unlike him does it sound. He does not treat the metaphysical in any conventional way, and does not make movies for dealers in subtexts, deep-readers, or people writing term papers; his films work backward in terms of theme: They are stories first, ones with human relationships that make Eastwood feel comfortable; later, someone, perhaps himself, can come and say that one is about loyalty, or about responsibility. Eastwood’s thought process, he explains, runs to small units, frame after frame. It’s the way the family was, he says, looking for an irony. ”My dad’s dream was to have a hardware store. I’m his son.” The pride is there, but the doubts dilute it every day.

”Did you once describe yourself as a bum and a drifter?” someone asked him in Paris.

”No,” Eastwood answered.

”Then what are you?”

”A bum and a drifter.”

That was Paris, and the line was not so much thrown but flipped away in Eastwood’s modified Smothers Brothers, California ԁеаԁраո. But the subject returned in London, and Eastwood rubbed it again, a man massaging an old ache that he assumes will last as long as he does.

”Wherever I came from, I always came out of left field. I wasn’t predicted to do anything. So it was easy to say that this guy was going nowhere. And then when he does try to do something, maybe that disappoints the soothsayers who’ve decided his type isn’t supposed to do anything at all.”

His pride, his sense of what is right, is intense and at times it comes close to a kind of puritanism. For an extraordinarily rich man, he gets extravagantly upset about the money and time spent on making films. His own, financed and distributed by Wаrոеr Brothers, and usually made by Malpaso, his production company, are expedited as if there were Oscars for the fastest shoots and most firsttakes to reach a final print. For a man who lives in the very protected elegance of Carmel, Calif., his clothes often look like K Mart and Sears, but this could be a kiss blown at his audience, the people who came to Clint Eastwood pictures when Rex Reed was describing them as a ”demented exercise in Hollywood hackery.”

Talking to people, he is gracious, tolerant, almost courtly. But he wants to be left alone about his former wife, whom he divorced after 25 years of marriage, and his friend, Sondra Locke, the actress, who frequently appears in his films. Little bits of himself work loose though. ”I’m always appalled, just knocked out by disloyalty,” he says. ”I never think it’s coming.” He tends to trust people, and sometimes wonders why:

”I was driving around my place in Carmel, and I saw this guy and his girl camping on it. I thought, ‘What the hell, they’re probably having a great time, let ’em stay.’ Later, I went back, and they had left the place a mess. I felt I had been had.”

When he talks about actors and films he likes, the names are not the Waynes and the Stewarts, like himself, the redwoods of the American movies. Instead, they are Montgomery Clift and James Cagney, Simone Signoret and Maggie Smith, ”Saturday Night and Sunday Morning” and ”Breaker Morant.” His descriptions of them are kind but cool, with Eastwood saving his passions for his audience, the single element, along with his instincts, that he seems to trust totally.

”I never second-guess audiences, because many times they’re just so much further ahead of you. And then sometimes, they miss what you think you’ve been explaining so simply. So you can’t second-guess. All you do is build on your own instinctive reactions. That tells you what to do. You do it the best way you know how, and you hope, of course, that somebody likes it.”

He insists he is ”no great intellect” and is uncomfortable with ”analyzing things too much.” It is not a sham retreat by an intelligent man into some kind of yokelism, but a very measured view of his own skills. He has always cut dialogue out of his films, and limited exposition because he feels the audience will catch on without it. Eastwood describes acting and directing as ”interpretive” functions, activities at a somewhat lower rung on his creative scale than writing a script. He waits for scripts, rather than commissioning them on a theme that interests him. The character of Dirty Harry, for example, was developed from a story by Harry Julian Fink and R.M. Fink. The script was originally meant for Frank Sinatra, but he got sick, and Eastwood took over the project, changing the personality of the detective. His next film, ”Pale Rider,” a western, is an exception to the pattern – Eastwood’s notion of a theme came first, and the movie was written to fit it. When he says he can pick out a good script, but does not have the ability to write one from scratch, it is as if he is drawing lines and saying: ”This is me. This isn’t me. My limitations are real.”

He harbors considerable anger against the critics who described him as an apologist for violence and no-nothingism. ”Those are the kind of people who become dictators and think they should run everybody. There’s an awful lot of people out there who want to tell everybody else what to do. . . . They’re always thinking in terms of all those poor lonely people who don’t know anything out there. It’s just a giant ego running around. . . . They’re putting themselves above and looking down saying this is what the masses see.”

Eastwood insists that he does not fully understand the reversal in the critical current about his work. The pattern of his films has not changed over the years – a smaller, more detailed, more complicated film, and then a popular one, broader in approach, the kind of enterprise that Graham Greene refers to as an ”entertainment,” as opposed to a novel. The same critics who notice that Wes Block, the cop in ”Tightrope,” is vulnerable and has ”problems,” may not have paid much attention to the fact that Josey Wales, almost 10 years earlier, had ”problems,” too: His entire family was wiped out by marauders. Sometimes, Eastwood says, he has the impression ”a couple of gray hairs don’t hurt.” Other times he assumes that the relative lack of commercial success of a couple of his more ambitious films probably has been a positive factor – ”Some critics just don’t approve of too much effective screen presence or too much success.” There is also the accumulation of continued effort: No one in Hollywood of any stature works as much.

You may like

Clint Eastwood

Mystic River: Why Clint Eastwood’s Best Movie Still Holds Up Today

A filmmaker of Clint Eastwood‘s caliber is going to have a filmography full of gems. Primarily known for his work in Westerns, biopics, and military dramas, every so often, Eastwood steps outside his comfort zone and delivers in a genre that would seem completely unexpected on paper. That happened in 2003 with Mystic River, a neo-noir murder mystery drama that seems a bit forgotten or overlooked, even though it was a financial success and earned six Academy Award nominations. It represents Eastwood at his very best, breathing vivid life into complex characters as he examines a plethora of themes that range from loyalty, friendship, revenge, and, ultimately, forgiveness.

Mystic River is based on the 2001 novel of the same name by Dennis Lehane, and it follows the lives of three childhood friends, Jimmy Markum (Sean Penn), Sean Devine (Kevin Bacon), and Dave Boyle (Tim Robbins), living in Charlestown, Boston in 1975. Dave is kidnapped by two men claiming to be police officers, and he’s sexually abused by them over a four-day period until he escapes. The traumatic event shapes the three friends, and they ultimately lead very different lives twenty-five years later.

Jimmy is an ex-con that now owns a convenience store in the neighborhood, Sean works for the Massachusetts State Police as a detective, and Dave is your everyday blue-collar worker that still lives with the trauma of being abducted and raped. Their lives are forced together once again through tragedy when Jimmy’s daughter Katie (Emmy Rossum) is found murdered, and friendship is tested when all signs point to Dave being the murderer.

Mystic River Is a Departure From Clint Eastwood’s Other Work

Eastwood tackles the material in Mystic River with a sure and confident hand. It also represents a unique departure from some of his other films. Much of the action takes place under the cover of darkness, and Eastwood is able to find beauty in that darkness. The filmmaker focuses on a character’s eyes or the gleam of a weapon, for instance, as darkness permeates most of the scene.

For the scenes that take place during the day, the filmmaker opts for tight close-ups that linger over the emotions of his impressive cast. There is something uncomfortably intimate about Mystic River, and that has much to do with the subject matter. None of this story is particularly easy to digest, and Eastwood adds to that discomfort with his choices to frame scenes in such a way that’s almost intrusive. The audience feels a growing sense of dread and tension as more of the story unfolds.

Using Lehane’s novel and Brian Helgeland’s screenplay as a blueprint, Eastwood profoundly explores generational trauma and how the sins of the past can leave a permanent mark on our present. Even though the abuse only happened to Dave, the effects of the event leave a mark on all three friends, with Dave being the primary victim and the others feeling a sense of survivor’s guilt for not being subjected to it themselves.

The ordeal forever changes their union because they’re never quite able to look at each other the same way again, as each friend deals with the trauma differently. Jimmy is stunned by the act of abuse but can’t give Dave the support he needs, which then bleeds into their present when Jimmy begins to suspect that Dave had something to do with his daughter’s murder. He doesn’t want to consider that his friend would do something like this because of the trauma he endured as a child, but as evidence mounts against him, Jimmy has to decide if friendship and loyalty overshadow his need for vigilante justice. The story is rich with so many complexities that make it some of Eastwood’s most compelling work as a filmmaker.

Eastwood also takes his time with the story and lets it unfold as it should. Mystic River is very nuanced, and he knows he’s dealing with heartbreaking subject matter that requires patience and respect. The story is grounded in so much reality that Eastwood seems keenly aware that a viewer might be an actual victim of this kind of abuse themselves, so he delicately approaches the topic and gives it the emotional weight it deserves.

He also shows the uncomfortable side of abuse where the victim, unfortunately, can be shamed because of the event. Dave becomes an outsider later in his life, even with his close friends, something that sadly comes along with this kind of trauma. Eastwood approaches all of this responsibly and provides a very balanced outlook to all the events transpiring on screen.

Mystic River has become known for its powerhouse performances, and Eastwood pulls the very best from his ensemble cast. While the scenes with the young actors are brief in the beginning, they set the tone of who these people will be twenty-five years later. Dave becomes the outcast because of the event; Jimmy lacks empathy and doesn’t trust authority, while Sean becomes the grounded one of the bunch and a police officer in an attempt to prevent a tragedy like this from ever happening again.

Clint Eastwood Pulls Powerhouse Performances From His Cast

Tim Robbins, Sean Penn, and Kevin Bacon do a great job conveying the unspoken tension between all three of these characters. There is a sense of loyalty, but so much has taken place over the years that it has forced them all to lead very different lives. As a group, they are uniformly excellent. You feel the history between the characters and the bonds that were broken, only to be reopened by a new traumatic event.

On their own, Penn gives the performance of a lifetime as Jimmy, and it’s not a shock that this turn finally earned him his first Academy Award for Best Actor. Penn is a dominant presence in all of his scenes, and there is a sense of uncertainty whenever he’s around because you don’t know exactly what move he will make.

That’s not to say he doesn’t display layers. All of that bravado is broken once he finds out his daughter is murdered. It’s hard to pinpoint a director’s best scene on film, but what Eastwood pulls out of Penn during the “Is that my daughter?” sequence represents some of his very best work as a filmmaker.

Robbins also received an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his work here, representing a much-deserved win. As Dave, Robbins is the tragic and emotional heart of the story. The viewer feels instant empathy for Dave due to what he went through as a child, but you’re also left questioning everything when it seems like Dave could be the one who murdered Katie.

Robbins keeps you on your toes throughout, making you question his innocence while also seeing the tenderness in him as he interacts with his own child, who is just about the age he was when he was abused. As for Bacon, of the three male leads, he gives the most subdued performance, but it suits the character. He’s trying to make everything right and keep it all together. It’s a subtle performance that carries its own emotional weight.

Eastwood also makes the supporting roles worthy of attention. Marcia Gay Harding, as Dave’s wife Celeste, puts in powerful work here that earned her a Best Supporting Actress Oscar nomination, while Laura Linney more than holds her own with Penn as his second wife, Annabeth. In addition, Laurence Fishburne also fills in as Sgt. Whitey Powers in another excellent part.

Mystic River is a haunting and poetic motion picture that showcases a director laying it all out on the table. Eastwood gives the audience everything he has as a director and pours it out across the screen in a film that is just as powerful twenty years after its initial release.

Clint Eastwood

Clint Eastwood’s Most Iconic Non-Western Role Was Only Possible Because Of This Actor

SUMMARY

Clint Eastwood’s role in Dirty Harry is considered one of his most iconic, and the film is a classic in the crime genre.

Paul Newman initially turned down the role of Harry Callahan in Dirty Harry but recommended Clint Eastwood for the part.

Newman declined the role due to his liberal beliefs, and Eastwood’s portrayal of Callahan differed from Newman’s perspective, but both respected each other.

SCREENRANT VIDEO OF THE DAY

Although Clint Eastwood first built his impressive career on Western movies like The Man with No Name franchise and The Outlaw Josey Wales, the actor’s biggest non-Western role in Dirty Harry is one of his most iconic, and it might have never happened without this one actor. Clint Eastwood began acting in the 1950s, and over several decades, became a staple in the Western genre. What makes Eastwood stand out is the fact that he has not only appeared in countless films, but has also directed them himself. Films like Unforgiven and Gran Torino have defined his career. However, Dirty Harry is by far one of Clint Eastwood’s best films.

In 1971, Clint Eastwood starred in the neo-noir action film Dirty Harry. The film, and its adjoining sequels, follow Inspector “Dirty” Harry Callahan, a rugged detective that is on a hunt for a psychopathic serial killer named Scorpio. The Dirty Harry franchise lasted from 1971 to 1988, and has since been considered a classic. In fact, Dirty Harry was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress because of its cultural significance. However, this film might have been vastly different if Clint Eastwood had never been in it, and scarily enough, this definitely could have happened back in 1971.

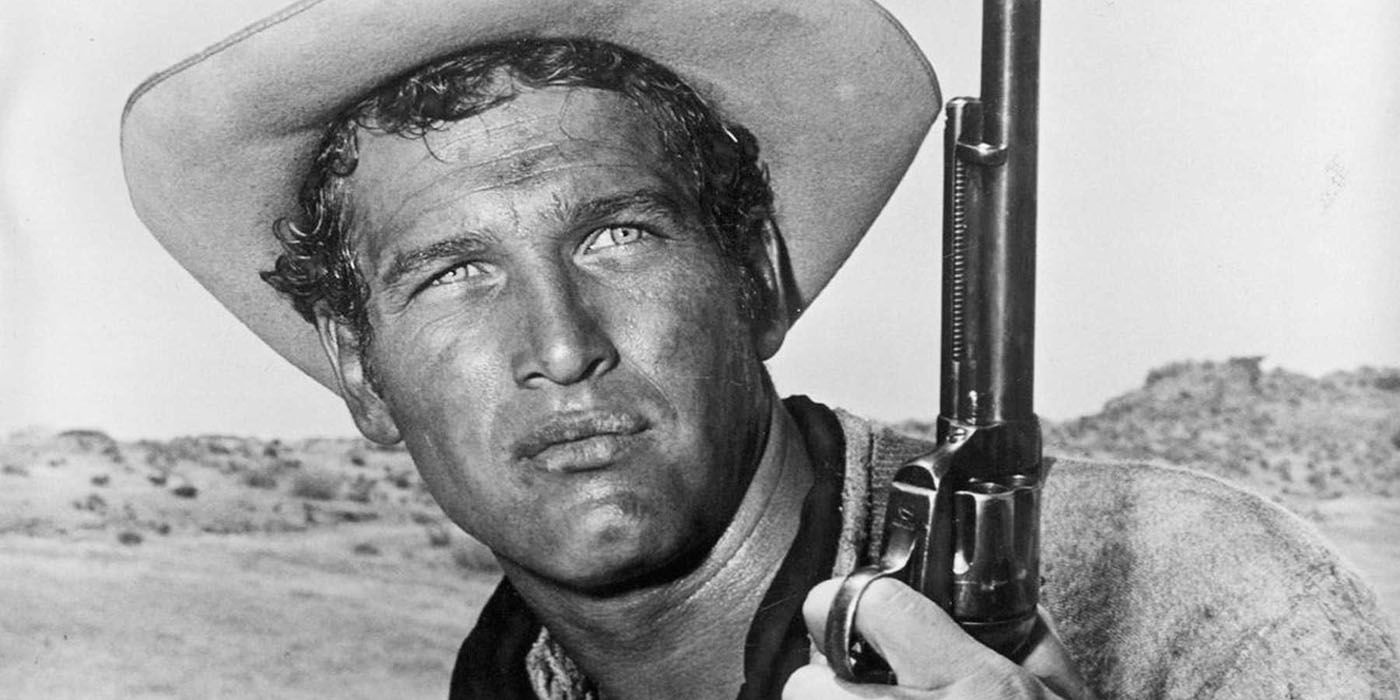

Paul Newman Rejected Dirty Harry Before Suggesting Clint Eastwood For The Role

Dirty Harry went through many production challenges before it was actually made, and one of those included casting the iconic detective. In the film’s early stages, the role was offered to actors such as John Wayne, Robert Mitchum, Steve McQueen, and Burt Lancaster. However, for various reasons, including the violence that permeates the film, these actors all declined. For a time, Frank Sinatra was attached to the project, but he also eventually left the production. In reality, Clint Eastwood wasn’t even in the cards for portraying Dirty Harry, but his big break came when Paul Newman was offered and declined the role.

Paul Newman, like many amazing actors before him, was offered the role of Harry Callahan, but ultimately said no. However, what makes his refusal stand out among the rest is that he recommended another actor that could be perfect for the role: Clint Eastwood. At this time, Eastwood was in post-production for his first film Play Misty for Me, meaning his career was taking something of a turn. Also, unlike his predecessors, Eastwood joined up with Dirty Harry, just as Newman thought he would. Because of his Western roots, the violence and aggression that made up Dirty Harry didn’t bother Eastwood at all.

Why Paul Newman Turned Down Dirty Harry

Paul Newman turning down the leading role in Dirty Harry may not seem too surprising considering the host of other actors that also declined the movie, but Newman definitely had his reasons. While previous actors had condemned the movie for its incredible violence and themes of “the ends justify the means,” Newman refused to take the role because of his political beliefs. Since Harry Callahan was a renegade cop, intent on catching a serial killer no matter the cost or the rules that would be broken, Newman saw this character as too right-wing for his own liberal beliefs.

Paul Newman was an outspoken liberal during his life. He was open about his beliefs, so much so that he even made it onto Richard Nixon’s enemies list due to his opposition of the Vietnam War. Other issues that Newman spoke out for included gay rights and same-sex marriage, the decrease in production and use of nuclear weapons, and global warming. As a result of his politics, Newman quickly denied the role of Harry Callahan. In an interview with Entertainment Weekly as reported by Far Out Magazine, Clint Eastwood commented that he didn’t view Callahan in the way Newman did, but still respected him as an actor and a man.

Would Dirty Harry Have Been So Successful Without Clint Eastwood?

Ultimately, it’s hard to say whether Dirty Harry would have been successful without Clint Eastwood. Arguably, any big-time actor could have made the film succeed solely based on their fame. However, one aspect of Dirty Harry and its carousel of actors is that the movie had various scripts, all with different plots. So, if Dirty Harry had been in a different location with a different serial killer and a different lead actor, there’s a chance it wouldn’t have been nearly as successful. In the end, Dirty Harry is a signature for Clint Eastwood, and most likely, audiences are lucky that it was made the way it was.

Clint Eastwood

The story of how Clint Eastwood prevented Ron Howard from embarrassment

A star of American cinema both in front of and behind the camera, Ron Howard is often forgotten when recalling the greatest directors of modern cinema, yet his contributions to the art form remain unmatched. Working with the likes of Tom Hanks, Chris Hemsworth, Russell Crowe and John Wayne, Howard has brought such classics as Apollo 13, A Beautiful Mind and Rush to the big screen.

Entering the industry in the late 1950s and 1960s, Howard started his career as an actor, making a name for himself in shows like Just Dennis and The Andy Griffith Show before his role in 1970s Happy Days would catapult him to national acclaim. His directorial debut would come at a similar time, helming 1977’s Grand Theft Auto, the ropey first movie in a filmography that would later become known for its abundance of quality.

Known for his acting talents, Howard wouldn’t become a fully-fledged director in the eyes of the general public until the 1980s, when he worked with Tom Hanks on 1984’s Splash and George Lucas for the 1988 cult favourite Willow.

With hopes of becoming the new Star Wars, Willow was instead a peculiar fantasy tale that told the story of a young farmer who is chosen to undertake the challenge to protect a magical baby from an evil queen. Starring the likes of Warwick Davis, Val Kilmer and Joanne Whalley, the film failed to make a considerable dent in pop culture at the time, largely being ridiculed by critics and audiences alike.

Screened at the Cannes Film Festival, the movie was spared humiliation by none other than Clint Eastwood, who saw the craftsmanship behind the picture, as described by Ron’s daughter, Bryce Dallas Howard.

Speaking to Daily Mail, the actor recalled: “My dad made a film called Willow when he was a young filmmaker, which screened at the Cannes Film Festival and people were booing afterwards. It was obviously so painful for him, and Clint, who he didn’t know at that time, stood up and gave him a standing ovation and then everyone else stood up because Clint did”.

Dallas Howard, who worked with Eastwood on the 2010 movie Hereafter, became very fond of Eastwood as a result, looking up to him as an exemplary Hollywood talent. “Clint puts himself out there for people,” she added, “As a director he is very cool, very relaxed, there’s no yelling ‘action’ or ‘cut’. He just says: ‘You know when you’re ready.’ I told my dad he should do that!”.

Take a look at the trailer for Howard’s 1988 fantasy flick below.

Trending

-

Entertainment10 months ago

Entertainment10 months agoJohn Wayne’s son speaks on military service, Hollywood life and his dad, ‘The Duke’ – My Blog

-

Entertainment10 months ago

Entertainment10 months ago40 Legendary John Wayne Quotes – My Blog

-

Entertainment11 months ago

Entertainment11 months agoNew biography reveals the real John Wayne – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoWhy one POPULAR ACTOR was FIRED from THE SONS OF KATIE ELDER and lost his career as a result! – Old western – My Blog

-

Entertainment10 months ago

Entertainment10 months agoHow Maureen O’Hara Broke Her Hand During Iconic Scene With John Wayne – My Blog

-

Entertainment11 months ago

Entertainment11 months agoRio Lobo (1970) marked the last collaboration between John Wayne and Howard Hawks. – My Blog

-

Entertainment11 months ago

Entertainment11 months agoDid John Wayne really have a good time filming 1972’s The Cowboys? – My Blog

-

Entertainment10 months ago

Entertainment10 months agoJohn Wayne and the ‘Bonanza’ Cast Appeared in This Epic Coors Light Commercial – My Blog