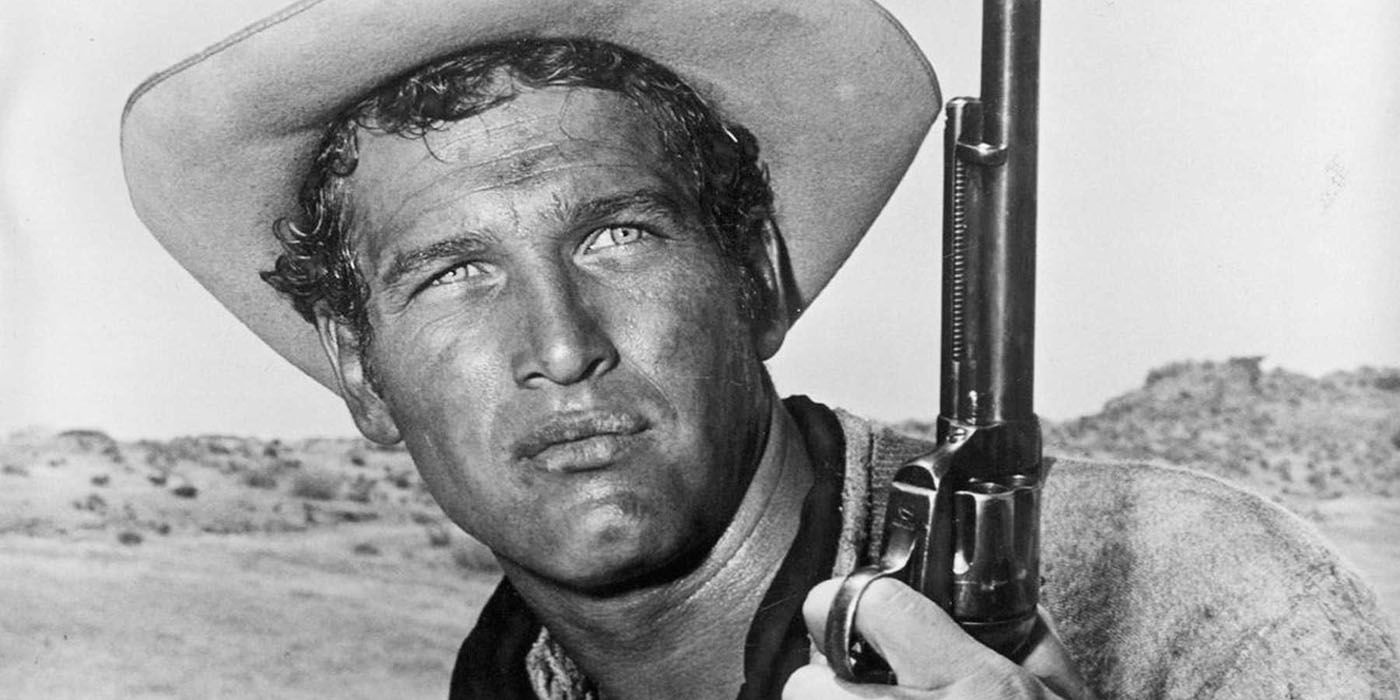

I feel a little bad for Clint Eastwood. What do you do after you become a legend? Post-Unforgiven, a film in which Eastwood wrestles with his own legacy and the western genre as a whole, his directing career has become divided between prestige pictures like Mystic River, J. Edgar, and American Sniper, films that seemed designed to just pass the time like Sully, Hereafter, and Changeling, and then there are the films that wrestle with legacy and old age, and in these films, Eastwood seems the most at home and personal. Movies like Million Dollar Baby and Gran Torino may not be perfect, but they show Eastwood grappling with his own image and what he will pass on to a future generation, and it’s in this vein that he directs one of his best films since Unforgiven, Cry Macho. The plot is barely there, but it doesn’t matter, because it’s not a plot-driven film. It’s a movie where Eastwood gives up the grit and gravel-voice tough guy for something quieter. It’s an embrace of the domestic, and it’s here that Eastwood brings an unexpected warmth to the picture that makes Cry Macho a surprisingly lovely experience.

Set in 1980, Michael Milo (Eastwood) is a broken-down old cowboy. He used to be a rodeo star with a knack for training horses, but that was a long time ago. His old employer Howard (Dwight Yoakam) comes to Milo asking the old guy to go down to Mexico and retrieve Howard’s estranged teenage son Rafo (Eduardo Minett), with whom Howard would like to restore their relationship. Milo at first refuses, but Howard reminds Milo that he floated the old cowboy through tough times and will continue to do so if Milo does him this favor. So Milo heads down to Mexico, finds the boy in the streets cockfighting with his rooster Macho, and convinces the kid to come back with him to Texas. However, along the way, they both find that a better life may be waiting for them away from America.

I feel a little bad for Clint Eastwood. What do you do after you become a legend? Post-Unforgiven, a film in which Eastwood wrestles with his own legacy and the western genre as a whole, his directing career has become divided between prestige pictures like Mystic River, J. Edgar, and American Sniper, films that seemed designed to just pass the time like Sully, Hereafter, and Changeling, and then there are the films that wrestle with legacy and old age, and in these films, Eastwood seems the most at home and personal. Movies like Million Dollar Baby and Gran Torino may not be perfect, but they show Eastwood grappling with his own image and what he will pass on to a future generation, and it’s in this vein that he directs one of his best films since Unforgiven, Cry Macho. The plot is barely there, but it doesn’t matter, because it’s not a plot-driven film. It’s a movie where Eastwood gives up the grit and gravel-voice tough guy for something quieter. It’s an embrace of the domestic, and it’s here that Eastwood brings an unexpected warmth to the picture that makes Cry Macho a surprisingly lovely experience.

Set in 1980, Michael Milo (Eastwood) is a broken-down old cowboy. He used to be a rodeo star with a knack for training horses, but that was a long time ago. His old employer Howard (Dwight Yoakam) comes to Milo asking the old guy to go down to Mexico and retrieve Howard’s estranged teenage son Rafo (Eduardo Minett), with whom Howard would like to restore their relationship. Milo at first refuses, but Howard reminds Milo that he floated the old cowboy through tough times and will continue to do so if Milo does him this favor. So Milo heads down to Mexico, finds the boy in the streets cockfighting with his rooster Macho, and convinces the kid to come back with him to Texas. However, along the way, they both find that a better life may be waiting for them away from America.

For its first act, you’re not really sure what Cry Macho is trying to do or where it’s going. But when you pull back and look at the full picture, you see that Eastwood is reframing his thoughts on his masculinity. You have to remember that when it comes to “macho” Hollywood guys, Eastwood helped defined the role with his work in westerns as well as the Dirty Harry franchise. Unforgiven turns all of that on its head in a compelling, thoughtful way, but what do you do after you create one of the greatest westerns of all time? What do you do after that kind of statement? Eastwood has been trying to figure that out for a couple decades now, and perhaps the answer lies in something as quiet and elegant as Cry Macho.

Once you get past the first act where Rafo’s mother (Fernanda Urrejola) tries (and fails) to seduce Michael and Michael and Rafo start to bond, the film coheres when their car breaks down in a small town and they find the possibility of peace and settling down. While I wouldn’t call Cry Macho a story of “redemption”—neither Michael nor Rafo have done anything particularly wrong—it is a story about finding peace, and that the way of conflict isn’t to be invited or conquered. From its opening, beautiful shots from cinematographer Ben Davis, you can tell that Eastwood is going for something more pastoral and somber. This isn’t the grizzled veteran telling a young man how to be a man by emulating his violent virtues (something Eastwood touched on with Gran Torino), but rather letting it all go to try and settle down.

It’s nice to see Eastwood embrace this vision of life. Nothing is going to erase The Man with No Name Trilogy or the Dirty Harry movies. That legacy is secure. But Eastwood knows he’s not that guy anymore, and it would be foolish to try. So instead it’s better to be grizzled, slow-moving Eastwood, and riding around with him and Rafo is like spending time with your Grandpa Clint. Sure, he may be a little ornery, but he’s also full of wisdom and he’s got a good heart. He’s suffered and he’s barely figured life out, but at least he knows it. He’s no longer carrying around anger, and any attempts to be macho at this time just look silly, which is why “macho” is personified by a literal cock. Not only that, but twice in the film when it looks like the only way out of a situation is through violence, Macho comes flying out, attacks the attacker, and the rooster, Rafo, and Michael are able to get away. In this way, Macho becomes a spirit animal of sorts, channeling the violence that Eastwood no longer wishes to perform or embrace. It’s also legitimately funny to watch some guy get owned multiple times by a rooster.

I don’t know what the grace note looks like on Clint Eastwood’s career, and I think something he’s struggled with is that he doesn’t know either. At times, it seems like filmmaking is merely a hobby for him. He makes relatively low-cost pictures for one studio (Warner Bros.), his prestige is enough to secure the financing and distribution, and he gets his films in on time and under budget. While this has led to some deeply underwhelming affairs and at times maddening efforts (hello, Jersey Boys), you try telling a 91-year-old Hollywood legend that it’s time to hang it up. You can’t force a grace note, but Cry Macho is as graceful as Eastwood has been in a long time.

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.