Entertainment

Every John Ford & John Wayne Western, Ranked – My Blog

Entertainment

Woman Attempting To Sleep With One Person From Every Country Shares The Worst Nationality In Bed

Entertainment

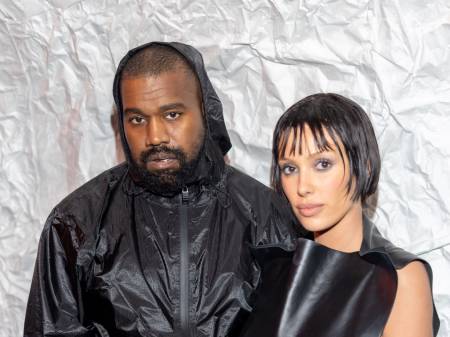

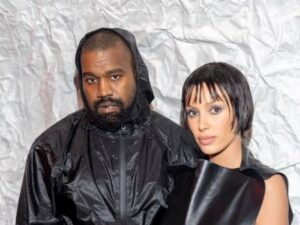

Kanye West Shares Provocative Video Of Wife Bianca In Bed And Fans Can’t Stop Pointing Out How Big It Is

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoJohn Wayne’s son speaks on military service, Hollywood life and his dad, ‘The Duke’ – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago40 Legendary John Wayne Quotes – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoNew biography reveals the real John Wayne – My Blog

-

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years agoWhy one POPULAR ACTOR was FIRED from THE SONS OF KATIE ELDER and lost his career as a result! – Old western – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoRio Lobo (1970) marked the last collaboration between John Wayne and Howard Hawks. – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoJohn Wayne and the ‘Bonanza’ Cast Appeared in This Epic Coors Light Commercial – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoHow Maureen O’Hara Broke Her Hand During Iconic Scene With John Wayne – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoDid John Wayne really have a good time filming 1972’s The Cowboys? – My Blog