When the upcoming biopic Daliland was announced as the closing night film for last year’s Toronto International Film Festival, one of its best-known actors was strangely left off the press release: Ezra Miller, the controversial star of The Flash, who plays the young Salvador Dali in flashbacks (Ben Kingsley as an older version of Dali is the film’s lead).

Miller was originally cast in Daliland in 2018, well before they started making headlines for all the wrong reasons – and Mary Harron, the director, has since made a point of describing them as one of the greatest actors she’s worked with. But it’s a reminder that no aspect of filmmaking sparks more argument than casting, sometimes even before audiences and critics see a frame of the final product, depending on the baggage attached to both actor and role.

Sometimes an actor just doesn’t look like what the fans had in mind. Sometimes it’s a matter of perceived talent or temperament, cultural background or life experience – or, as in Miller’s case, whether they’re thought to deserve any sort of movie career.

One way or another, there’s no doubt that mistakes can be made, even if it’s not always the fault of the actors concerned. Here’s our list of some of the more questionable casting choices of all time … or are any of these performances worth defending? Let the debates begin …

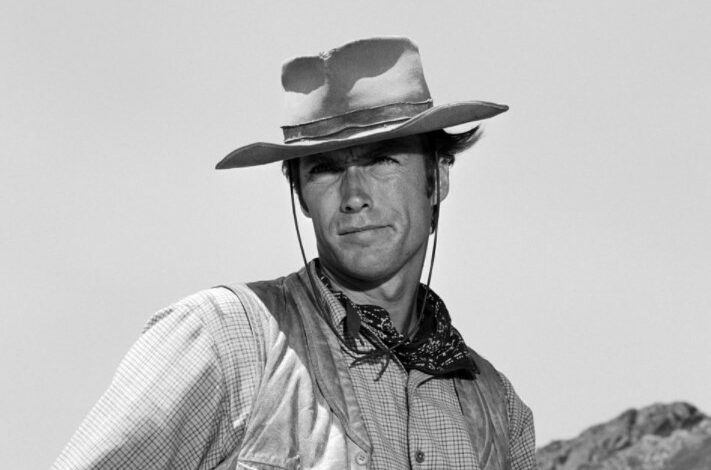

John Wayne as Genghis Khan in The Conqueror (1956)

Oh dear.CREDIT:GETTY

Oh dear.CREDIT:GETTY

Hollywood’s greatest cowboy star as a Mongol chief? To be fair, Dick Powell’s Technicolor epic isn’t far in spirit from a Western, desert backdrops included (the Utah locations were downwind of a nuclear testing site, which is a whole other story). Still, there’s no escaping the camp value of Wayne decked out in swarthy make-up and Fu Manchu moustache, making no effort to alter his all-American drawl. That’s before we get to the bizarre S&M dynamics of the plot, which starts out with the barbaric hero kidnapping a fiery Tartar maiden (Susan Hayward). “Your future promises much discomfort,” he informs her. Sounds about right.

Mick Jagger in Ned Kelly (1970)

Mick Jagger and his bushranger beard.

Mick Jagger and his bushranger beard.

Bushrangers were the rock stars of their day, the British director Tony Richardson must have reasoned, so why not bring an actual rock star over to Australia to play the most famous bushranger of them all? But over the course of the trip down under Jagger’s usual cockiness somehow drained out of him, leaving him to recite Ned’s lines in an uncertain Irish accent like a schoolboy aware of not having done his homework (pouty and wispy, he also anticipates Kodi Smit-McPhee in The Power of the Dog). “Such is loife” never sounded less profound.

Lucille Ball in Mame (1974)

Lucille Ball with Robert Preston in the “almost psychedelic” musical Mame.CREDIT:WARNER BROS

Lucille Ball with Robert Preston in the “almost psychedelic” musical Mame.CREDIT:WARNER BROS

Singing ability isn’t always a prerequisite in musicals, as was proven by Rex Harrison in My Fair Lady among others. But when an exhausted-looking Ball is rasping her way through one overscaled production number after another, it’s anyone’s guess what she was expected to bring to the role of Auntie Mame, in theory an eternally stylish non-conformist and life force. Less of a mystery is why Hollywood musicals like this one stopped being made: like other grandiose old-school productions from the same era, this one feels so out of its time, the film almost psychedelic.

Robert De Niro as the Creature in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994)

Robert De Niro in the 1994 film Frankenstein – a disaster.CREDIT:GETTY

Robert De Niro in the 1994 film Frankenstein – a disaster.CREDIT:GETTY

Kenneth Branagh’s BBC-style take on the novel starts out watchable enough, but from the moment De Niro lurches into view as the scarred, grunting monster, the whole thing starts looking like a metaphor for itself: the story of a would-be visionary whose passion project turns into a total disaster. De Niro is revisiting territory he covered more successfully in Cape Fear, but his earnest efforts to feel himself into the creature’s skin are a big part of the problem. By contrast, John Cleese does surprisingly well in a non-comic role as the hero’s mentor (whose brain becomes the Creature’s – though De Niro thankfully doesn’t attempt a Cleese impression).

Anne Heche and Vince Vaughn as Marion Crane and Norman Bates in Psycho (1998)

Anne Heche in the ill-advised 90s remake of Psycho.CREDIT:REUTERS

Anne Heche in the ill-advised 90s remake of Psycho.CREDIT:REUTERS

Gus van Sant’s shot-by-shot remake of the Alfred Hitchcock classic was a bold experiment, but the nature of experiments is that they don’t always succeed. Look at his version of the crucial scene where Marion, a thief on the run, checks into the Bates Motel and gets into conversation with its youthfully anxious manager. As if reacting against the perceived theatricality of the original, Heche and Vaughn strive for an offhand ’90s naturalism that removes most of the tension from the encounter, and suggests a couple of students stumbling their way through an exercise in acting class.

Keanu Reeves in Constantine (2005)

Keanu Reeves: definitely a skinny blond geezer from Liverpool.CREDIT:WARNER BROS

Keanu Reeves: definitely a skinny blond geezer from Liverpool.CREDIT:WARNER BROS

Reeves’ acting has copped its share of unjust criticism, and characters in comic-book movies don’t always have to resemble their counterparts on the page. Still, in this case fans had some reason to be annoyed. Co-created by British comic legend Alan Moore, the “occult detective” John Constantine was originally a skinny blond geezer from Liverpool, usually seen in a tan trench coat and physically modelled after Sting. His Hollywood equivalent is… very much not that, although in hindsight we can see him as a first draft of a more enduring Keanu alter ego named John, black tie, deep voice and all.

Robert Pattinson as Salvador Dali in Little Ashes (2008)

Robert Pattinson mumbles and smirks his way through Little Ashes.

Robert Pattinson mumbles and smirks his way through Little Ashes.

Miller wasn’t the first screen Dali to run into trouble. Often an awkward, self-conscious screen presence, Pattinson has rarely been more so than in this ill-fated arthouse production made just after the original Twilight, chronicling the art school days of the future surrealist legend Dali and his buddies Luis Bunuel (Matthew McNulty) and Federico Garcia Lorca (Javier Beltran, a genuine Spaniard flanked by two Brits doing accents). The film doesn’t work, but is Pattinson’s mumbling, smirking performance as terrible as it first appears? Or is it apt enough for a character who is constantly posing yet hasn’t quite worked out who he wants to be?

Nicole Kidman as Lady Sarah Ashley in Australia (2008)

Nicole Kidman in Australia: an outright mistake.CREDIT:20TH CENTURY FOX

Nicole Kidman in Australia: an outright mistake.CREDIT:20TH CENTURY FOX

Common sense suggests that not one person could be right to play Virginia Woolf, Diane Arbus, Grace Kelly and Lucille Ball, but over her long career Nicole Kidman has risen to the occasion more often than not. If there’s one item in her filmography that qualifies as an outright mistake, it’s her twittery turn as her heroine of Baz Luhrmann’s chaotic super-sized melodrama, a haughty aristocrat who falls for a rugged drover (Hugh Jackman). All the character’s tics are exaggerated to the point of pantomime, which is the Baz hallmark, but drastically reduces any prospect of us being touched by the romance.

Ashton Kutcher in Jobs (2013)

Ashton Kutcher working on his intensity in Jobs.CREDIT:AP

Ashton Kutcher working on his intensity in Jobs.CREDIT:AP

Justice where it’s due: kitted out with the mop-top, the wire-rimmed glasses and the facial hair, Kutcher does look quite a bit like the young Steve Jobs. He has the hunched posture down, and has clearly worked hard on the gestures. But his attempts at intensity don’t appear to have any thought behind them, beyond “I am being intense”. Truthfully, the 2015 Steve Jobs biopic wasn’t much of a movie either, despite an Aaron Sorkin script and a more dynamic central performance from Michael Fassbender. Maybe software development just isn’t as dramatic a subject as people think.

Renee Zellweger in Judy (2019)

Zellweger, squinting and simpering her way through Judy?

Zellweger, squinting and simpering her way through Judy?

Yes, she won the Oscar, but let’s be serious. Judy Garland was a powerhouse who poured her heart out every time she appeared on screen. Renee Zellweger squints, simpers, tilts her head, flutters her eyelashes, and generally does a fair-to-middling job of reproducing her subject’s mannerisms, without a trace of the spirit. Perhaps the core problem isn’t so much miscasting as the folly of anyone trying to compete with a performer who dramatised herself as no-one else could. At any rate, long after Judy is forgotten, Judy Garland will still be loved.

Daliland is in cinemas from July 13.

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Oh dear.CREDIT:GETTY

Oh dear.CREDIT:GETTY Mick Jagger and his bushranger beard.

Mick Jagger and his bushranger beard. Lucille Ball with Robert Preston in the “almost psychedelic” musical Mame.CREDIT:WARNER BROS

Lucille Ball with Robert Preston in the “almost psychedelic” musical Mame.CREDIT:WARNER BROS Robert De Niro in the 1994 film Frankenstein – a disaster.CREDIT:GETTY

Robert De Niro in the 1994 film Frankenstein – a disaster.CREDIT:GETTY Anne Heche in the ill-advised 90s remake of Psycho.CREDIT:REUTERS

Anne Heche in the ill-advised 90s remake of Psycho.CREDIT:REUTERS Keanu Reeves: definitely a skinny blond geezer from Liverpool.CREDIT:WARNER BROS

Keanu Reeves: definitely a skinny blond geezer from Liverpool.CREDIT:WARNER BROS Robert Pattinson mumbles and smirks his way through Little Ashes.

Robert Pattinson mumbles and smirks his way through Little Ashes. Nicole Kidman in Australia: an outright mistake.CREDIT:20TH CENTURY FOX

Nicole Kidman in Australia: an outright mistake.CREDIT:20TH CENTURY FOX Ashton Kutcher working on his intensity in Jobs.CREDIT:AP

Ashton Kutcher working on his intensity in Jobs.CREDIT:AP Zellweger, squinting and simpering her way through Judy?

Zellweger, squinting and simpering her way through Judy?

John Wayne | Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

John Wayne | Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images