John Wayne

How Gary Cooper Indirectly Gave John Wayne His First Big Hollywood Break

John Wayne

The Legend Lives On: John Wayne is Still Alive!

John Wayne

Why John Wayne Turned Down the Chance to Work With Clint Eastwood

John Wayne

Ann-Margret Refused to Call John Wayne ‘Duke’ While Introducing 1 of His Movies

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoJohn Wayne’s son speaks on military service, Hollywood life and his dad, ‘The Duke’ – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago40 Legendary John Wayne Quotes – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoNew biography reveals the real John Wayne – My Blog

-

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years agoWhy one POPULAR ACTOR was FIRED from THE SONS OF KATIE ELDER and lost his career as a result! – Old western – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoRio Lobo (1970) marked the last collaboration between John Wayne and Howard Hawks. – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoJohn Wayne and the ‘Bonanza’ Cast Appeared in This Epic Coors Light Commercial – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoHow Maureen O’Hara Broke Her Hand During Iconic Scene With John Wayne – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoDid John Wayne really have a good time filming 1972’s The Cowboys? – My Blog

20th Century FoxCooper had rocketed to stardom at the end of the silent era, and broken through in a big way thanks to Victor Fleming’s sound Western “The Virginian.” Everyone wanted a piece of Cooper in 1930, including Raoul Walsh, who was about to helm a frontier Western called “The Big Trail.” The filmmaker was keen to cast Cooper as Breck Coleman, a young fur trader seeking revenge for the murder of his friend.

20th Century FoxCooper had rocketed to stardom at the end of the silent era, and broken through in a big way thanks to Victor Fleming’s sound Western “The Virginian.” Everyone wanted a piece of Cooper in 1930, including Raoul Walsh, who was about to helm a frontier Western called “The Big Trail.” The filmmaker was keen to cast Cooper as Breck Coleman, a young fur trader seeking revenge for the murder of his friend. 20th Century FoxWhen it came time to figure out the billing for “The Big Trail,” everyone agreed that Morrison was in dire need of a new moniker. The director suggested Anthony Wayne, after the “Mad” Revolutionary War general (largely because he’d been reading a biography of the military legend at the time). Fox deemed this “too Italian” (Wayne was incredibly Irish), at which point they settled on a compromise: John Wayne.

20th Century FoxWhen it came time to figure out the billing for “The Big Trail,” everyone agreed that Morrison was in dire need of a new moniker. The director suggested Anthony Wayne, after the “Mad” Revolutionary War general (largely because he’d been reading a biography of the military legend at the time). Fox deemed this “too Italian” (Wayne was incredibly Irish), at which point they settled on a compromise: John Wayne.

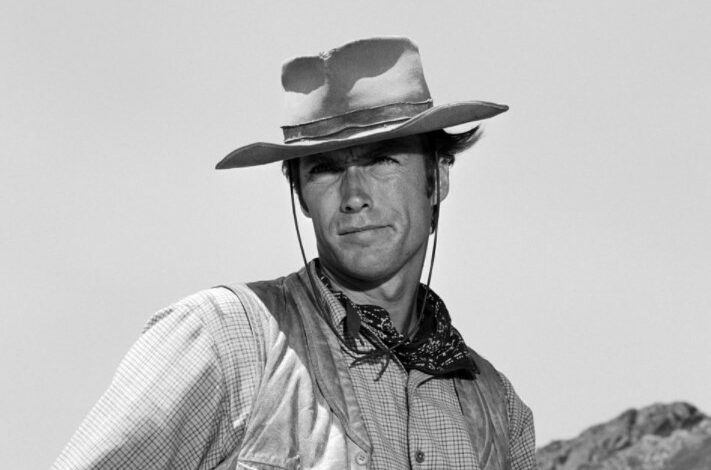

John Wayne | Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

John Wayne | Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images