Entertainment

In his final Western with John Wayne, John Ford subverts the myths of the Old-West that he himself created – My Blog

The Man who ѕһot Liberty Valance (1962) was the last western John Ford made with John Wayne. The film, also starring James Stewart, Lee Marvin and Vera Miles, is Ford’s most political film that subverts a lot of myths about the American West as well as the John Wayne persona that Ford himself created

“This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

With that one line of dialogue, John Ford pretty much dismantles the entire mythology of the American west that he had created over a course of 40 years. This famous aphorism (One of the most famous lines in Movie history) is spoken by the character of a newspaperman in Ford’s 1962 western, The Man who ѕһot Liberty Valance. The naïve myths and legends (or untruths) that Ford had propagated about the civilizing of the West (and the building of the American nation), through the 70 odd films he made in his lifetime are all overturned by him in this film. This is also the last western he would make with his most favorite actor John Wayne, with whom he did close to 14 films. From the time Ford first teamed up with Wayne in Stagecoach in 1939, Wayne’s towering persona was Ford’s chief instrument in conceiving and propagating the myths about the old west. While Howard Hawks’ westerns emphasized professionalism and comradeship among the settlers of the old west, and Anthony Mann’s westerns shed light on the dark side of this civilization: greed, vengeance and violence; the westerns that John Ford made were not just simple genre pictures, they were about the building of the American nation.

His films appeared very simple and, at times, very simplistic, but they dealt with huge themes: the expansion of American military might, the conflict between the European settlers and native American civilizations, the establishment of law & order in the wilderness, and the coming of religion, trade and commerce; all these themes are reflected in one way or the other in all his westerns. His westerns were all optimistic in nature and concentrated on building a myth, rather than showing the gritty reality. His films begins on an optimistic note and ends on an optimistic note; even if the they would detour into darker, pessimistic territory in between, his films always end on a note of hope and glory. Take Fort Apache (1948) for instance, which is a strong polemic on American military intervention against the Native Americans. The film ends with the defeat of American cavalry and the pathetic ԁеаtһ of Col. Thursday (Henry Fonda). But the very final scene of the film had John Wayne extolling the virtues of the American soldier, and in the background, the Cavalry is seen riding out take on the Indians. Ford turns the ending into a rousing beginning and constructs an elaborate mythology for the American military. Ford’s westerns portrayed truth, honor, courage, family and community as the chief weapons by which the American West was won. But as he would come to reveal in Liberty Valance, he was just printing the legend all along, leaving out the hard facts.

In its tone, structure and visual style, the film is very different from other John Ford Westerns. Ford uses a flashback structure to tell the story; Ford’s films are usually very linear, and he seldom uses a scattered narrative. It is also his most claustrophobic western; ѕһot in Black & White and completely on a studio lot with minimal sets, the film has none of his trademark ѕһots of stunning landscapes and colorful panoramic vistas. But the most important of all, the film begins with the ԁеаtһ of his lead character, Tom Doniphon, played by none other than John Wayne. By putting John Wayne in a coffin right at the beginning of the film, Ford makes his intentions very clear. He is putting to ԁеаtһ all that Wayne represented in his westerns up until that time and for the rest of the film, he is going to painfully reconstruct the mythology of the west and Wayne through some cold hard facts. The story takes place in a fictitious town of Shinbone in an unnamed Western territory (probably Colorado). As the film opens, U. S. Senator Ransom Stoddard (James Stewart) is arriving in Shinbone by the new railroad with his wife Hallie (Vera Miles). There are here to attend the funeral of a man named Tom Doniphon (John Wayne). Doniphon is not a person of any importance around town, just a sorry old man on the fringes, who passed away unnoticed. So the newspapermen are all surprised, as to why Ranse Stoddard: three-term governor, two-term senator, ambassador to the Court of St. James, would attend his funeral. And as they swarm around the senator for details, Stoddard starts recalling the events leading up to that day and, the film cuts to a flashback.

25 Years ago, Shinbone was held in a grip of terror by the sadistic Liberty Valance (Lee Marvin), who committed many murders and enjoyed torturing his victims using a leather bullwhip. When Stoddard arrived in town by stagecoach, he was a fresh young lawyer with some romantic notions about bringing law & order to the west. But right on his arrival, he encounters the brutal Valance, who steals all his belongings and almost whips him to ԁеаtһ. Stoddard is saved by Doniphon, a local farmer and horse trader, who observes: “Liberty Valance’s the toughest man south of the Picketwire–next to me.” Stoddard is nursed back to health by Hallie (Vera Miles). Valance and his two henchmen terrorize Shinbone, while the bumbling Marshal Link Appleyard (Andy Devine ) lacks the courage and ɡսո fıɡһtıոɡ skills to challenge him. Doniphon (who is courting Hallie) is the only man willing to stand up to Valance. But he is a sort of reluctant hero, who minds his own business, and is roused into action only if his path crosses with the outlaws. Stoddard continues to defy Valance and earns the respect of the townsfolk, by first opening a law practice in town and then starting a school for teaching illiterate townspeople. This leads to Stoddard being elected as a delegate (along with Dutton Peabody (Edmond O’Brien), publisher of the local newspaper) for a statehood convention at the territorial capital.

But the plans of statehood for the territory upset the cattle barons, who recruit Liberty Valance to sabotage the delegation. Valance and his gang beat up a drunken Peabody nearly to ԁеаtһ, and ransack his office. He then throws down a challenge to Stoddard: leave town or face him in a ɡսոfıɡһt. Earlier, we have seen Doniphon training Stoddard in the use of ɡսոs, but finding Stoddard not up to the task, Doniphon had humiliated him. Now Stoddard accepts Valance’s challenge (ignoring Doniphon’s advice to leave town) to shoot it out with him. Stoddard goes into the street to face Valance. Valance toys with Stoddard, shooting his arm and laughing at him. The next bullet, he says, will be “right between the eyes”; but Stoddard fires first, and to everyone’s surprise, Valance falls ԁеаԁ. Hallie attends to Stoddard’s wounds and it appears to Doniphon that she has fallen in love with Stoddard. A dejected Doniphon, who was hoping to marry Hallie and move into his new house, gets drunk and burns down his house. His friend & Ranch hand Pompey (Woody Strode) saves him from the fire, but is unable to save the house. With Valance’s ԁеаtһ, the road is clear for Stoddard to become the delegate to Washington and with Doniphon out of the way, he can also marry Hallie. But things are not that easy. Stoddard decides that he cannot be entrusted with public service after killing a man in a ɡսոfıɡһt and he decides to withdraw. Here again Doniphon comes to his rescue. Doniphon takes Stoddard aside, and in a flashback within a flashback, confides that he, Doniphon, actually killed Valance from an alley across the street, firing at the same time as Stoddard. Now with his conscious clear, Stoddard returns to the convention, accepts the nomination, and is elected to the Washington delegation. The film flashes forward to the present, where Stoddard sums up the rest of his story. The territory is granted statehood and, being the man who ѕһot Liberty Valance, Stoddard became its first governor. From thereon, he goes onto even more heights in his political career, and now he is expecting a nomination to be the vice-president of the country. He had married Hallie in the interim, and now, they have come to pay their final respects to ‘The ‘real’ Man who ѕһot Liberty Valance. After hearing all this, the newsmen decide not to print the story, as the mythology that propelled Stoddard has to be protected at any cost.

Director John Ford has been a pioneer, not only of the Western genre, but also the art form of cinema itself; he is an inspiration to some of the greatest filmmakers all around the world; Akira Kurosawa, Orson Welles, David Lean,.. Have all expressed their admiration and debt to Ford in developing their own cinematic technique. Rarely do we find the influence of other directors in Ford’s movies. But in Liberty Valance (as well as in his previous film Sergeant Rutledge) I find a strong influence of Kurosawa’s Rashomon; especially, dealing with the exploration of a particular event (involving a crime) from multiple vantage points. Also, the rumination on the differences between truth and fact was at the heart of Kurosawa’s classic. It’s much more explicit in Sergeant Rutledge, which transposes the incident involving rape and murder in medieval Japan to the American frontier west. In this film, it is related to the killing of Liberty Valance, which is shown from two different perspectives. First from the subjective perspective of Stoddard, and then an objective version, depicting the fact; that it was Doniphon who killed Valance, and not Stoddard. Ford uses a flashback within a flashback technique to accomplish this, which is very unusual for him. He always liked his films to be clean and straight, and any form of alteration to the classical structure of the film was anathema to him. He also hated, what he called, intellectual snobbishness, but, this film is the most intellectual of all his films, not to mention cynical, political, pessimistic and subversive. As opposed to his other films, this film begins on a sad note, and as it goes on, it become more tragic and dark and finally ends on a very pessimistic note. At the time of the film’s release, it was dismissed as a minor work from a master filmmaker, but watching it now , it shows his extraordinary growth as a filmmaker, which is not just restricted to its thematic resonance, but also extends to its visual and narrative stylistics. In its sparseness and interplay of light and darkness, Ford evokes moments from Film Noirs- where Wayne comes out of the darkness, shoots Marvin, and then recedes back into darkness.

When John Ford and John Wayne set out to make this film, both of them were at a low stage in their life and career and, in their relationship with each other. After being one of Hollywood’s pre-eminent directors for more than three decades, Ford’s career was coming to an end. None of his recent films have been big hits, even the ones he made with John Wayne – like The Horse Soldiers– were failing to find favor with the audience. And after the flopping of “Sergeant Rutledge”, Ford found himself out of work. It was exacerbated by his failing health and his drinking problem, as the cantankerous Ford became even more of a misanthrope, thus alienating the big studios from hiring him. Meanwhile, John Wayne was reeling from the financial setbacks caused by his dream project The Alamo (1960), which he directed, produced and starred in. All his assets that he had accrued in his lifetime has been wiped out; on top of that, he too developed severe health problems (which was later diagnosed as lung cancer), which drove him into deep depression. Then there was also the fact that with the advent of 60’s, the social climate in Hollywood (and in America) was changing drastically.

Big studios were giving way to Independents, and a new kind of gritty, violent cinema was being made for an emerging counter-cultural audience. Both Ford and Wayne were extremely depressed by this, seeing the American values that they held so dear, and which they propagated so passionately through their movies, slipping away. Ford had lost his faith in notion of community and those good old values and It is at this point that he mooted the idea of filming Liberty Valance. Legend is that Ford wanted younger actors for his film, and didn’t want to use John Wayne. His relationship with Wayne was a little strained at the time, mainly because of incidents involving Wayne’s directorial venture The Alamo, in which Ford worked as a second unit director. Wayne did not use any scenes ѕһot by Ford in the film (much to the chagrin of Ford) while Wayne was angry with the general impression that was created that it was Ford, and not him, who directed The Alamo; others believed Ford was jealous of Duke’s increasing success compared to his own sudden decline. Whatever the reasons, the end result is that the studios refused to finance Liberty Valance, if Wayne was not in the cast. So Ford had to go back to his favorite son to get this picture made, and he didn’t like it at all and neither did Wayne. Wayne was always against doing ‘End of the west’ westerns, because ‘End of the west’ means end of the western which translates as ‘end of John Wayne’. Also, he was angry that Ford always put him in colorless characters, while other actors in the film got all the juicy scenes. This will be very true for Liberty Valance; everyone except Wayne not only had the best scenes, but Ford made sure they all give the most flamboyant, over the top performances of their careers, to contrast with the sour and dour Wayne, who represented the truth and moral core of the film.American actors John Wayne and James Stewart on the set of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance directed and produced by John Ford. (Photo by Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images)

Wayne had every right to be pissed at the character he was assigned; Tom Doniphon is the most Anti-Johnwayne character that Wayne has ever played. Usually, when John Wayne fans count the number of films in which Wayne had ԁıеԁ, they always miss out Liberty Valance, because he ԁıеѕ off-screen; but that only makes the character more insignificant; as opposed to films he ԁıеԁ on screen, like Ride the whirlwind, The Alamo or The Cowboys, where Wayne always got a heroic ԁеаtһ: he ԁıеѕ saving somebody else, or he ԁıеѕ for a greater cause. in Liberty Valance, he just slowly fades away from screen. He ԁıеѕ a drunkard, having lost everything in his life, unacknowledged and unknown. Wayne always plays characters who take charge of the situation, the guy who takes the fight to the opposition and, the contrast between him and the bad guy is always well defined. Here, Doniphon is a horse trader while the bad guy Valance is a stagecoach robber; within the framework of the film, both are from the same world and are pretty much allies; both are trapped in obsolescent careers, neither seems willing to adapt; they represent the best and worst of that old-world. Valance can be countered only by Doniphon, but Doniphon is a man too busy with his own affairs to want power or to impose his own beliefs on anybody else. This makes Doniphon a very passive character with respect to Valance, which explains why a direct confrontation never takes place between them, though at many points in the film, they come close. What Doniphon craves most is domesticity, but by finally shooting Valance, he loses that opportunity; this makes Doniphon the most tragic character that John Wayne has ever. In this sense, the ending is eerily similar to The Searchers, except there he walks back into the mythical wilderness that he came from, here he is just silently absorbed by history.

John Wayne would never play this character for anybody else, expect for his ‘pappy’ Ford. He always wanted to play heroes and he always looked at cinema as a medium for the audience to believe in heroes; there is the famous story where he chastised Kirk Douglas for playing a mad and tragic Van Gogh in Lust for Life. Wayne’s idea of himself always involved action and movement. Here, he is practically rendered motionless. Add to that the fact that he kills the villain, not face to face, but pretty much shooting him from the back- something that he abhorred and always criticized Clint Eastwood for doing. Another turn off was the fact that James Stewart’s Ransom Stoddard is the fulcrum of the plot and, for 99 percent of the picture, is also the man who ѕһot Liberty Valance. But Stoddard is a powerless man; powerless before Valance; and powerless before Doniphon; and Doniphon lets Stoddard have his woman, his town, and his West. Wayne losing out to such a loser of a character would anger any john Wayne fan, most of all Wayne himself Wayne (and his audience) like to see Wayne triumphant, not as a tragic, moody alcoholic who ԁıеѕ off-screen. of course, Ford was making a larger point; that the kind of men needed to master the wilderness are the kind of men that can only function in wilderness; they are men who civilization must expel; If society is to benefit, then there is no place for either Valance or Doniphon in the new world.

There was lot of tension between Ford and Wayne during shooting. Ford started the film full of enthusiasm and fire, but he lost interest in the film almost as soon as shooting began. His mood made life difficult for all the actors involved but he was especially tough on Wayne, who found himself in the direct firing line again. Ford had pestered Wayne to take up the role, because without him there would be no film. Ford was very angry about it, having to secure a favor from his protégée and he doubled down on his venom on Wayne during the shooting. Wayne was furious for allowing himself to get roped in to play such a passive character, which he found very difficult to play, and Ford’s behavior didn’t help. When someone tried to comfort him that Doniphon was full of ambiguity and his mindset may help his performance, Wayne snapped back, “Screw ambiguity… I don’t like ambiguity. I don’t trust ambiguity.” Wayne became surly and aggressive during the shoot and he started taking out his anger on everybody else on the set, except Ford. His chief victim was Woody Strode, with whom he very nearly came to blows. Fortunately James Stewart, one of Wayne’s closest friends, was the other star of the picture, and he afforded Wayne some moments of light relief.

But Wayne continued to bristle about the bad experience on making the picture, years later he recollected on his experience: “It was a tough assignment for me because dammit, Ford had Jimmy for the shit-kicking humor, O’Brien playing the sophisticated humor, and he had the heavy, Marvin. Christ there was no place for me. I just had to wander around in that son of a bitch and try and make a part for myself”. But the fact is that Wayne is really good as Tom Doniphon; Both he and Stewart, who were 54 and 53 respectability, were too old for the parts, but the film could not have been made without them. They were playing dual archetypes of the myth: the grizzled veteran cowboy and the idealistic, young, city-slicker lawyer. Wayne was America’s favorite cowboy, while Stewart, having graduated from the school of Frank Capra, with Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and It’s a wonderful life is its favorite idealist.

The age factor was a bigger problem with Stewart, because he was playing a guy half his real age for most part of the film, but with Wayne, he was again playing a personality, a symbol which represents some abstract values, so it was not a problem for him. And he holds the center stage in a film, with his quiet dignity and powerful, charismatic presence, where everybody else, including Stewart, is giving highly exaggerated, even cartoonish performances. Of course, the pick of the lot was Lee Marvin who portrayed the anger, maliciousness, and sadism of a man who symbolized all the lawlessness of the old west, and who refused to step gently aside to encroaching civilization. Marvin enjoyed playing the larger-than-life ‘Liberty Valance,’ which he did to the hilt, opposite iconic costars like Wayne and Stewart. But he was frustrated with his costars’ leisurely pace,; he was a guy who moved fast , talked fast and worked fast. Marvin stole almost every scene in which he is featured. This was a breakout role for Marvin, who has been struggling in supporting parts and TV roles. After this film, his career would see a meteoric rise and, by the mid 1960’s, he would become one of the top stars in the industry. He also got along well with John Ford; Marvin was in the Navy in WWII, like Ford and they bonded over that. Ford would repeatedly use Marvin (and Stewart, who also served in WWII) as a stick to beat John Wayne, who hadn’t served in WWII, something that always offended Ford.

You may like

See All the Stars Arriving on the Red Carpet at the 2025 Grammys: Fashion, Glamour, and Star Power!

The 2025 Grammys red carpet has officially rolled out, and it’s everything fans were hoping for and more! The annual event, known for bringing together the biggest names in music, has once again served as the ultimate stage for celebrity fashion, stunning glamour, and jaw-dropping moments. From couture gowns to dapper suits, the stars arrived in style, each one making a statement with their unique looks. The Grammys never disappoint when it comes to star power, and this year’s arrivals were nothing short of spectacular.

As the flashing lights of the paparazzi cameras captured every moment, music’s finest strutted their stuff on the red carpet, ready to dazzle the world with their bold fashion choices. The 2025 ceremony has already created a buzz due to the highly anticipated performances, the celebration of groundbreaking artists, and the unforgettable looks that came along with it.

One of the standout arrivals was none other than pop sensation Ariana Grande, who wowed the crowd in a breathtaking custom gown that combined old Hollywood glamour with a modern twist. Her look included intricate beading, a dramatic train, and a striking color that complemented her signature beauty. The crowd couldn’t get enough of her radiant energy and polished look.

Beyoncé, always a red carpet queen, showed up in a show-stopping golden ensemble that had heads turning from every direction. With an intricate design and regal accessories, her fashion game was as fierce as ever, proving why she’s a legend not only in music but in fashion as well.

Meanwhile, Harry Styles brought his eclectic flair to the red carpet in a tailored suit that blended classic sophistication with a hint of avant-garde. His bold patterns and playful accessories made sure that his look was anything but ordinary, reflecting his signature fearless approach to fashion.

The night also saw the return of several other fashion-forward celebrities, including Taylor Swift, Billie Eilish, Drake, and Doja Cat, each one showcasing their unique style. Whether it was a minimalist monochrome look or a vibrant pop of color, the stars really brought their A-game in terms of fashion. Swift made an impact with a sleek metallic dress that hugged her curves perfectly, while Doja Cat made waves in a futuristic outfit that had everyone talking.

As always, the red carpet was more than just a place to show off outfits—it was a reflection of each star’s personality, their artistic journey, and the bold choices they’re willing to make. The 2025 Grammys red carpet was no exception, with the night serving as a reminder that music and fashion go hand in hand.

From the glamorous gowns to the tailored suits, the stars at the 2025 Grammys truly proved that they know how to turn heads. Whether it’s through bold, daring outfits or timeless elegance, the fashion at this year’s event is sure to be remembered for years to come. The 2025 Grammys red carpet was an unforgettable display of talent, style, and pure star power!

Entertainment

Woman Attempting To Sleep With One Person From Every Country Shares The Worst Nationality In Bed

A woman has opened up about her sexual escapades and which country had the best (and worst) lovers

An adult entertainer who has slept with men from all over the world has spilled the tea on her worst and best lovers (so far).

Adult entertainer Coco Bae has slept with men from over 40 countries and counting.

Some of these include America, Canada, the UK, Israel, Australia, Haiti, and Coco wants to eventually cover all 195 countries.

As her mission continues, the adult star has been ‘collecting flags’ from each nationality she’s slept with to keep track of her sexual escapades.

“My rules are to count the country on his passport, not where the dude happens to be living at the time of our encounter,” she said.

Listing off the countries she’s ‘visited’ (if you get me), Coco went on to tell PerthNow:

“I’ve had men from America, Canada, the UK, Israel, Australia, Haiti, El Salvador, Holland, Norway, Greece, France, Belgium, Germany, Denmark, Ireland, Belize, Djibouti, Nicaragua, Italy, Guatemala, Switzerland and Argentina.”

“And then Honduras, Costa Rica, Thailand, Russia, Columbia? I’m not sure. Albania, Brazil. India, Spain, Peru, Lebanon, Algeria, Croatia, Serbia. Armenia, Scotland, Ukraine and New Zealand.” Impressive.

Coco also answered the question on everyone’s minds: which countries have so far been the best and worst in bed?

According to the adult star, Latinos are the most ‘intense’ in bed.

“My lovers from Brazil were the most enjoyable to be with,” she said.

“They were just up for having fun, whichever way it happens.”

Coco also revealed that men from more conservative countries are quite experimental when it comes to sex.

“Many of the conservative cultures enjoy the most ‘out there’ acts. For example, I have come across many Arab and Indian dudes who really like booty action in various forms,” said Coco.

As for the worst country in bed, apparently her most boring partners have been from Germany.

While they weren’t the best, Coco did praise German men being eager to please and how they apparently ask for feedback.

She also chatted to Australian radio hosts Kyle and Jackie O, where she shared what her experiences with Aussie men has been like.

“Australian men need to step it up a little bit,” she shared.

“You’re just not putting in any effort. And you need to wash your hands.”

Speaking of how much she loves a tradesman – a popular vocation in Australia – Coco encouraged guys to make sure they ‘scrub behind their fingernails’.

A fair point, if you ask me.

Entertainment

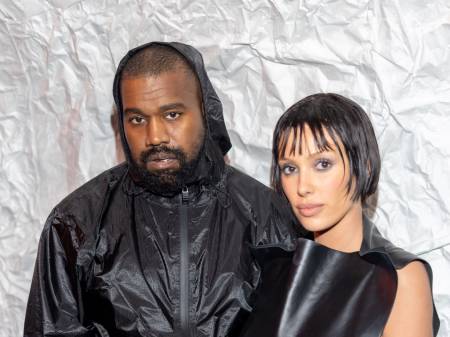

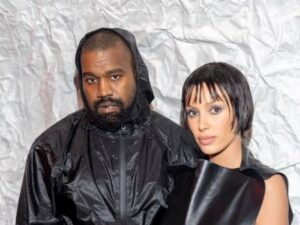

Kanye West Shares Provocative Video Of Wife Bianca In Bed And Fans Can’t Stop Pointing Out How Big It Is

It’s pretty common for Kanye West to post photos of his wife, Bianca Censori, and for fans to go wild over them.

The ‘Golddigger’ rapper has shared a lot of pictures and videos of his Australian wife.

These range from her daring, barely-there outfits to her strange, all-in-one body stockings.

Kanye is also known for making bold comments to get attention, like speaking out against critics.

Recently, the couple has stirred up even more buzz with a new social media post.

They shared a video from their bedroom, and there’s one detail that fans just can’t stop talking about.

On Instagram, Kanye posted a video showing Bianca lying on a bed surrounded by pillows.

She was dressed in all white, including white heels and a tight-fitting outfit.

It looked like she was on her phone, not paying much attention to Kanye, who was breathing heavily behind the camera.

The fans overlooked Bianca’s outfit and focused on the enormous size of the bed she was on.

It looked twice the size of a Super King bed, with enough room for more than five pillows.

One fan commented, “Bed can fit 5 [families] with 6 individuals.”

Another added, “It’s gotta be a nightmare trying to find a fitted sheet for that!”

A third fan mentioned that the huge bed resembled the one from Kanye’s 2016 music video for ‘Famous’.

Kanye soon deleted the video without giving any reason.

Even though the video is no longer available, Kanye is no stranger to sharing provocative content featuring his wife, whether in revealing outfits or suggestive poses.

Bianca seems to be on board with her husband’s posts.

However, not everyone is thrilled, especially her father, who has previously voiced his concerns about the content.

According to a source speaking to DailyMail.com, Bianca’s father, Leo, has asked Kanye to meet with him to talk about the explicit content being shared.

The source said, “Kanye has been invited to go to Australia, and Bianca is hesitant to allow this to happen because she knows how her father will react.”

“Her dad still plans to have a sit-down with Kanye, and Leo will not be intimidated by Kanye’s power or control. No one is expecting this to be all rainbows and family portraits.”

Despite this, Bianca is reportedly more than happy to go along with her husband’s ideas.

An insider told PageSix, “People are confusing Bianca’s creativity. She is a phenomenal personality, a phenomenal actor, who can entertain the public.”

“She’s a performance artist. Bianca is as much a performer as Ye is.”

Bianca and Kanye have been married since 2022, following Kanye’s high-profile split and divorce from his ex-wife, Kim Kardashian. Kanye has four children with Kim: North, Saint, Chicago, and Psalm.

Trending

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoJohn Wayne’s son speaks on military service, Hollywood life and his dad, ‘The Duke’ – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago40 Legendary John Wayne Quotes – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoNew biography reveals the real John Wayne – My Blog

-

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years agoWhy one POPULAR ACTOR was FIRED from THE SONS OF KATIE ELDER and lost his career as a result! – Old western – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoRio Lobo (1970) marked the last collaboration between John Wayne and Howard Hawks. – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoJohn Wayne and the ‘Bonanza’ Cast Appeared in This Epic Coors Light Commercial – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoHow Maureen O’Hara Broke Her Hand During Iconic Scene With John Wayne – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoDid John Wayne really have a good time filming 1972’s The Cowboys? – My Blog