Entertainment

“John Wayne, an actor, was more important to the mass psyche than any single American president – My Blog

Jack’s statement .Jack Nicholson on the Duke: “John Wayne, an actor, was more important to the mass psyche than any single American president.” Do you agree with Jack?

It’s just like I always said, that John Wayne, an actor, was more important to the mass psyche than any single American president. His longevity, his penetration—all of that ultimately has affected how human beings behave, what choices they make, who they think they are, more than any straight pragmatic political action and groupthink.Jack Nicholson, Vanity Fair, August 1986’d known that, I would have put that patch on thirty-five years earlier.

—John Wayne

On April 7, 1970, the night of the forty-second presentation of the Academy Awards, Hollywood’s annual celebration of industrial-strength narcissism, film’s elite gathered at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in downtown Los Angeles to honor the pictures, actors, directors, cinematographers, screenwriters, and other skilled artists and technicians that were chosen by the Academy’s voting members as the best of the previous year.

John Wayne, nominated for his performance in Henry Hathaway’s True Grit, faced strong competition: Richard Burton in Charles Jarrott’s Anne of the Thousand Days, a star vehicle for the hugely popular Burton and the odds-on favorite in Vegas; Dustin Hoffman for his scarily brilliant work in John Schlesinger’s blistering Midnight Cowboy; Jon Voight in the same film for his poignant depiction of innocence corrupted; and the magnificent Peter O’Toole sorrowfully wasted in the cringe-worthy, no-chance musical version of Goodbye Mr. Chips, directed by Herbert Ross.

Three significant events took place that evening. The first was the official acceptance of late-bloomer Jack Nicholson into the Hollywood mainstream, who would go on to dominate it for the rest of the twentieth century and into the first decade of the twenty-first. He was nominated in the category of Best Performance by an Actor in a Supporting Role, for his portrayal of the sympathetic, charming, and exceedingly vulnerable Hanson, a relatively small role that not only yielded an utterly unforgettable performance but signaled a cultural shift in American movies’ image of who and what a hero was.

The second was the awarding of a noncompetition, honorary Academy Award to Cary Grant, one of the giants of the industry’s golden age. Grant’s film career began in 1932 and lasted until 1966, when, still at the top of his game, he wisely chose to retire from the industry and go out on top. Now, four years later, he was finally being recognized for his remarkable accomplishment in helping to establish the iconic image of the romantic Hollywood leading man. It was hard to believe that Grant, who had appeared in so many films for many of Hollywood’s greatest directors (some greater than others, but most arguably made their best films with him), among them Alfred Hitchcock, George Cukor, Howard Hawks, Frank Capra, Leo McCarey, Stanley Donen, and Michael Curtiz, had never been officially acknowledged by his peers with a competitive Oscar. Grant, who was considered a troublemaker by the major studios because of his insistence on going freelance in an age of contract players, the first to do so and the first to pay for his freedom by being refused a real Oscar, was reduced to tears when, late in life, he finally received his honorary statuette.

The third, and perhaps most fascinating, was the competitive Best Performance by an Actor Oscar that John Wayne won for his self-parodic performance as Rooster Cogburn. Of the 164 movies he made in his long and brilliant career, including the twenty-four he did with John Ford, True Grit is perhaps the least Oscar-worthy in terms of pure cinema. However, for his long-overdue recognition—17 of the films he appeared in were among the 100 highest-grossing films of all time, collectively grossing more than $400,000,000 (in twentieth-century dollars), and since 1951 he had consistently placed among the top ten box-office stars—this was the one Hollywood chose to acknowledge Wayne’s great contribution to American movies.

His astonishing body of work, those 164 movies over a fifty-year span, where he upheld not just the law of the land but the American way, defined him as Hollywood’s definitive Indian-fighting (and later on Indian-defending), two-fisted, six-gunned, wagon-trained, swinging-bar-doored, maiden-preserving, democracy-defending all-American hero, the most enduring on-screen symbol of the vanishing prairie. And, although he was never in the military, he fought America’s enemies in World War II with patriotic propaganda films that came complete with recruiting stations set up in theater lobbies. He was an avowed enemy of Communism and especially American Communists. At the height of his career, he set about to rid Hollywood of both and did a fairly effective job. However, by age sixty-three, with the wear, the tear, the weariness on his craggy face, with cobra eyes that looked almost Asian, and the sagging body of a Hollywood life ridden hard and put away wet, he was considered passé by Hollywood’s young ’70s honchos, some not yet even born when Wayne made some of his best movies.

He had been nominated twice before, once as an actor in 1949 for Best Actor in Allan Dwan’s no-frills war movie Sands of Iwo Jima, when he lost to Broderick Crawford in Robert Rossen’s neopolitical All the King’s Men (a role Wayne turned down because he disliked the film’s political message), and once as producer (Best Picture/Batjac, his own production company) in 1960, for his post-Disney adult version of the classic story of The Alamo, which he also directed. Wayne lost that time to producer/director Billy Wilder for The Apartment.

Why was Wayne perennially passed over? For one thing, he made enemies in the industry where many never forgave him for his politics, and because of it, some of his greatest performances, like Ethan Edwards in John Ford’s The Searchers, were famously ignored by the voters of the Academy. Made during the height of the blacklist, The Searchers provides not just the best performance in any Hollywood film of 1956, but one of the greatest performances in any film anytime, anyplace, anywhere. Five years earlier, Stanley Kramer’s monumental High Noon, a western written and coproduced by blacklisted Carl Foreman, was nominated for eight Oscars and won four, including Best Actor for Wayne’s friendly rival for most of their careers, Gary Cooper. Why? Perhaps part of the reason is that Wayne was the former president of the radical-right Motion Picture Alliance, begun by Walt Disney, Sam Wood, and others in the early ’40s, the tea-party-style posse of a politically divided Hollywood that helped ruin the careers of some of its best talent (and biggest moneymakers), including Foreman. In 1971, an unrepentant Wayne told Playboy magazine, I’ll never regret having helped run Foreman out of this country. It was not hard to tell which side the Academy was on.

But it wasn’t only politics. As larger than life as he was for audiences, to the Hollywood studios that employed him and the voting Academy members, Wayne was, almost to the end of his career, considered a glorified B movie actor, his films never considered quality or art, certainly not worthy of Oscar. The studio book on Wayne was that he was just another Hollywood cowboy, that he didn’t have the emotional range of a Jimmy Stewart, the gritty elegance of a Spencer Tracy, the spitting toughness of a Humphrey Bogart, the street smarts of a Jimmy Cagney, the beautiful pain of a Marlon Brando, the urban cynicism of a William Holden, or the inherent populism of a Henry Fonda, all Oscar winners. He was just there, Hollywood’s unanointed Duke, as dependable as oats. Yet, as film critic and historian Andrew Sarris, promulgator of American auteurism, rightly acknowledged on the occasion of Wayne’s True Grit nomination, his forty years of movie acting and thirty years of damn good movie acting . . . Wayne’s performances for John Ford alone are worth all the Oscars passed out to the likes of George Arliss, Warner Baxter, Lionel Barrymore, Paul Lukas, Broderick Crawford, Jose Ferrer, Ernest Borgnine, Yul Brynner and David Niven . . . ironically, Wayne has become a legend by not being legendary.

And after Wayne’s Oscar win, Sarris explained his special appeal: I remember responding to him in a relatively uncomplicated way though he seldom functioned as a conventional hero. He could be accursed or obsessed . . . And on many other occasions the characters he played faced a twilight existence of loneliness and dependency . . . Wayne’s most enduring image, however, is that of the displaced loner vaguely uncomfortable with the very civilization he is helping to establish and preserve . . . At his first appearance we usually sense a very private person with some wound, loss, or grievance from the past.

THE NIGHT BEFORE THE OSCARS, Wayne was on location in Old Tucson, Arizona, shooting Rio Lobo, the third and weakest film of a trilogy of late-career westerns for Wayne directed by Howard Hawks. When his day’s filming was finished, Wayne flew in his private plane to LAX, where he was met by a limo and driven directly to the Beverly Hills Hotel. His third wife, Peruvian-born Pilar Pallete, and their three children, Aissa, fourteen, John Ethan, eight, and Marisa, three, were already there, waiting for him.They had arrived earlier in the day and checked into two of the hotel’s exclusive private bungalows, one for Wayne and Pilar and one for the kids. A bungalow over was an already sloshed Richard Burton and his wife, the equally inebriated Elizabeth Taylor.

Wayne and Pilar spent a quiet night together, and the next morning he was driven alone downtown to the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion to rehearse for that evening’s big event. His arrival drew the biggest reaction so far from the fans already filling in the bleachers on either side of the red carpet, some arriving at daybreak to catch a glimpse of their favorite stars. They didn’t stop screaming, mostly positively, for Wayne from the time he emerged from the limo until he passed through the private entranceway of the Pavilion. Someone in the bleachers held up a sign that read JOHN WAYNE IS A RACIST. If he saw it, he showed no visible reaction.

After being made up in his dressing room and running through his paces—where to go, where to stand, what hand to use to accept the statuette if he won, which side of the stage to exit—there were still a couple of hours to go before showtime. He lingered backstage, an informal schmooze space for nominees and friends, to see who else had arrived. Fueled now with drink, he told all the stars there who were interested, and the few who weren’t, that he didn’t think he had any chance in the world of winning. For one thing, he went on, he was too old, that the Academy preferred younger winners to keep bringing new audiences to the movies. For another, in a Hollywood that was making Easy Rider and Midnight Cowboy, his films had gone out of fashion.

He hated both of those pictures. Their drug-taking, antiestablishment themes, and, to him, glorification of homosexuality were all the proof he needed that he and his MPA gang had won the political battle against Hollywood’s Commies but had lost the moral war. Easy Rider was perverted and Midnight Cowboy a love story about two fags . . . And what did Midnight Cowboy have to do with anything about cowboys anyway? Always polite, when Wayne ran into Dustin Hoffman backstage he graciously told him that he enjoyed his performance in the film.

As for his own in True Grit, it was, as far as he was concerned, essentially the same character he’d played since John Ford’s 1939 Stagecoach some thirty years earlier, the only difference being that he was older. They hadn’t given him an Oscar for that one, and he figured they wouldn’t give it to him now.

There were two more rehearsals, for lights, cameras, and sound. By 2:00 in the afternoon, as the dancers, techies, camera operators, lighting focusers, and stage managers with earphones and clipboards crisscrossed the stage, Wayne found himself alone in the crowd. His mood brightened at six when Pilar arrived. She had left the kids with a sitter at the hotel thoughtfully provided by the Academy, which frowned upon children backstage during the big night. He saw her and smiled, the familiar grin that buried his eyes inside a squint and spread out and flattened his thin-lipped face. He swooped Pilar up in his arms the way he once famously had Maureen O’Hara in John Ford’s 1952 The Quiet Man, and the young Natalie Wood in Ford’s 1956 The Searchers, and carried her that way back to his private dressing room. He poured them each a drink as they patiently waited for the stage manager to knock on his door, open it halfway without looking in, call places, and shut it behind him.

The telecast began promptly at 7:00 Eastern Standard Time. The live TV show opened with a filmed montage of Hollywood’s greatest all-time stars, after which Gregory Peck marched onstage, his eyes ringed with glasses, and in his stentorian voice introduced each of that night’s nominees, as they walked out and took a bow.

Wayne received the loudest ovation.

The last to take the stage was the show’s honorary host, Bob Hope (there was no single official host that year), wearing a patch over one eye to spoof Wayne’s performance as Rooster Cogburn in True Grit. The audience roared. It was the best indication yet that Wayne might at last win his longed-for and long overdue Oscar.

Wayne took Pilar to their seats on the aisle down front. Like all the major category nominees and their spouses or dates, they were placed close to the stage, the lesser ones put farther back. As the ceremonies rambled on, Glen Campbell, one of Wayne’s costars, came out to sing the film’s theme, True Grit, one of the evening’s five songs nominated as Best. Campbell finished to a smattering of applause that sounded louder on TV than it did live, Wayne’s cue to quietly slip backstage and prepare for his entrance as a presenter for Best Cinematography.

When he walked out this time, he received a standing ovation and waited for the audience to quiet down before he spoke. I’m an American actor, he said. I work with my clothes on. A few giggles, a bit of applause. No one was quite sure in this era when it had become fashionable for actresses to go nude in mainstream films where he was going with that. His comic timing was, as always, less than perfect. I have to. Horses are rough on your legs and your elsewheres.Ah. Laughter sprinkled throughout the house. He then opened the envelope and announced the winner, Conrad Hall, for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Soon after he presented the golden statuette to Hall, the two left together, stage right. During a commercial break in the action, Wayne was escorted back to his seat.

Almost at the end of the four-hour-plus marathon, it was after eleven in New York, well beyond prime time, the Best Actor award was finally presented. The winner of the previous year’s Best Actress Oscar, Barbra Streisand, handed it out. Streisand, sparkling in pink, after smiling and flitting around the stage in a grand star sweep, read the names of the nominees. Only three were actually present, and each had a TV camera trained on him. Jon Voight was standing in the wings, Richard Burton was in his seat looking supremely uninterested. Wayne, seated not far away from Burton, squeezed Pilar’s hand. Babs teased the audience by opening the envelope as slowly as possible, looking at the name, and then saying, I’m not going to tell you! A light rumble of impatience rippled through the audience before she belted out in show-stopping ballad mode “JOHN WAYNE IN ‘TRUE GRIT’!”

He bolted out of his seat, propelled as much by shock as glee. He unbuttoned his jacket as he walked briskly to the stage, no sign of his famous, oft-parodied pigeon-toed small-step gait. Standing at the microphone, he looked a bit heavy, his unnaturally brown toupee sitting on his head like a muskrat, giving Wayne’s face an oddly unnatural box shape. He kissed Streisand lightly on the cheek without looking at her as she handed him his award, and then let out a breath-filled Wow filled with a lifetime of hopes, dreams, frustrations, and accomplishments. He lightly wiped a line of sweat from below his right eye with the knuckle of a bent forefinger and said, If I’d known that, I would have put that patch on thirty-five years earlier. He waited for the genuine laughter to die down, then continued. Ladies and gentlemen, I’m no stranger to this podium. I’ve come up here and picked up these beautiful gold men before, but always for friends. One night I picked up two—one for Admiral John Ford and one for our beloved Gary Cooper. I was very clever and witty that night, the envy even of Bob Hope, but tonight I don’t feel very clever, very witty. I feel very grateful and very humble, and owe thanks to many many people. I want to thank the members of the Academy; to all you people who are watching on television, thank you for taking such a warm interest in our glorious industry. Good night.

That was it. Short and sweet, no long and meaningless list of people to thank that nobody knew or cared about. As he stepped away from the mike, the music came up and Streisand, who had been standing behind and to the left, took him by the arm, and led him off stage right, to a career’s worth of resounding applause.

After, Wayne spent two hours patiently answering questions for the press and posing for the paparazzi, with and without Pilar. Then they were off to the traditional Governor’s Ball, the most prestigious party of the night. They didn’t get back to the Beverly Hills until nearly one A.M.

Burton, meanwhile, empty-handed, had left immediately after the ceremonies with Taylor, and the two went straight back to the hotel, skipping all the parties, preferring to be alone, where they could drink, piss, bitch at, and moan to each other.

A little after one o’clock in the morning a pounding came on the Burtons’ door. When neither one opened it, fear washing over them in this era of Charles Manson paranoia, Wayne, alone now and completely wasted, kicked it in as easily as if it were a stage prop. A stunned and frightened Burton and Taylor clutched at each other as they stared at him in silent disbelief. A grim-looking Wayne walked over to Burton, held out his Oscar stiff-armed like he was ready to tackle someone with it, and said, slowly, in that each-word-is-a-sentence style of his, You should have this, not me.

After that, the mood changed. All three stayed up the rest of the night, drinking nearly ’til dawn, schmoozing and laughing and telling stories, along the way Burton confessing he was certain he would never win an Oscar, Wayne assuring him his day would come (it never did).

The next morning Wayne and Pilar and the children were driven to the airport for the flight back to Old Tucson. Playtime was over and for Wayne there were still a few more miles of film to shoot before he slept.

Robert Morrison was born in 1782, the newest addition to the John Morrison British-Scottish-Irish clan of Counties Antrim and Donegal. While still a teenager, young Robert became active in the Free Irishman Movement that was opposed to the rule of the British Crown. Later on, when a warrant was issued for his arrest that would have certainly meant imprisonment and execution, he and the rest of the Morrisons hurriedly gathered their belongings and, in the black cover of the night, boarded a freighter bound for America.They arrived in New York in 1799 and, still fearing the long reach of British justice and its East Coast thug enforcers, continued west, following along the rivers and trails of Ohio, Kentucky, and Illinois before settling in Iowa, where they believed they were safe at last. Robert became a ruling elder in the Presbyterian Church and a brigadier general in the Ohio militia. He married and had a son named Marion—an Old French derivative for Mary or Marie, used by the British and Irish for males since medieval times—who fought in the Civil War and was wounded in the Battle of Pine Bluff.

Marion’s son was the outgoing and ambitious Clyde Morrison, who attended the University of Iowa, in Iowa City, to earn a degree in pharmacy. He hoped to start a practice in Des Moines, which was still mostly farm country, and although Clyde had never worked a yard of land in his life, he figured all these farmers, and their wives and children, would need medicine and family supplies. Marion was not just smart; he was big and strong enough to make the university’s all-star football team.

He had another, perhaps more surprising talent. Doc, as everyone called him, possessed a deep and sonorous singing voice. Whenever he was asked to at the university’s social gatherings, and even sometimes when he wasn’t, he loved to break into song. If slightly annoying in its arrogant braggadocio, there was also something undoubtedly charming about a big, handsome, hulking athlete who loved to sing.

At one such university social gathering, a diminutive, vivacious blue-eyed redhead named Mary (Marion) Brown, sometimes called Molly, heard the tall, husky Doc perform, was charmed and, despite being pursued by all the handsomest and well-set young men at the college and in town, decided he was the one she was going to marry.

You may like

See All the Stars Arriving on the Red Carpet at the 2025 Grammys: Fashion, Glamour, and Star Power!

The 2025 Grammys red carpet has officially rolled out, and it’s everything fans were hoping for and more! The annual event, known for bringing together the biggest names in music, has once again served as the ultimate stage for celebrity fashion, stunning glamour, and jaw-dropping moments. From couture gowns to dapper suits, the stars arrived in style, each one making a statement with their unique looks. The Grammys never disappoint when it comes to star power, and this year’s arrivals were nothing short of spectacular.

As the flashing lights of the paparazzi cameras captured every moment, music’s finest strutted their stuff on the red carpet, ready to dazzle the world with their bold fashion choices. The 2025 ceremony has already created a buzz due to the highly anticipated performances, the celebration of groundbreaking artists, and the unforgettable looks that came along with it.

One of the standout arrivals was none other than pop sensation Ariana Grande, who wowed the crowd in a breathtaking custom gown that combined old Hollywood glamour with a modern twist. Her look included intricate beading, a dramatic train, and a striking color that complemented her signature beauty. The crowd couldn’t get enough of her radiant energy and polished look.

Beyoncé, always a red carpet queen, showed up in a show-stopping golden ensemble that had heads turning from every direction. With an intricate design and regal accessories, her fashion game was as fierce as ever, proving why she’s a legend not only in music but in fashion as well.

Meanwhile, Harry Styles brought his eclectic flair to the red carpet in a tailored suit that blended classic sophistication with a hint of avant-garde. His bold patterns and playful accessories made sure that his look was anything but ordinary, reflecting his signature fearless approach to fashion.

The night also saw the return of several other fashion-forward celebrities, including Taylor Swift, Billie Eilish, Drake, and Doja Cat, each one showcasing their unique style. Whether it was a minimalist monochrome look or a vibrant pop of color, the stars really brought their A-game in terms of fashion. Swift made an impact with a sleek metallic dress that hugged her curves perfectly, while Doja Cat made waves in a futuristic outfit that had everyone talking.

As always, the red carpet was more than just a place to show off outfits—it was a reflection of each star’s personality, their artistic journey, and the bold choices they’re willing to make. The 2025 Grammys red carpet was no exception, with the night serving as a reminder that music and fashion go hand in hand.

From the glamorous gowns to the tailored suits, the stars at the 2025 Grammys truly proved that they know how to turn heads. Whether it’s through bold, daring outfits or timeless elegance, the fashion at this year’s event is sure to be remembered for years to come. The 2025 Grammys red carpet was an unforgettable display of talent, style, and pure star power!

Entertainment

Woman Attempting To Sleep With One Person From Every Country Shares The Worst Nationality In Bed

A woman has opened up about her sexual escapades and which country had the best (and worst) lovers

An adult entertainer who has slept with men from all over the world has spilled the tea on her worst and best lovers (so far).

Adult entertainer Coco Bae has slept with men from over 40 countries and counting.

Some of these include America, Canada, the UK, Israel, Australia, Haiti, and Coco wants to eventually cover all 195 countries.

As her mission continues, the adult star has been ‘collecting flags’ from each nationality she’s slept with to keep track of her sexual escapades.

“My rules are to count the country on his passport, not where the dude happens to be living at the time of our encounter,” she said.

Listing off the countries she’s ‘visited’ (if you get me), Coco went on to tell PerthNow:

“I’ve had men from America, Canada, the UK, Israel, Australia, Haiti, El Salvador, Holland, Norway, Greece, France, Belgium, Germany, Denmark, Ireland, Belize, Djibouti, Nicaragua, Italy, Guatemala, Switzerland and Argentina.”

“And then Honduras, Costa Rica, Thailand, Russia, Columbia? I’m not sure. Albania, Brazil. India, Spain, Peru, Lebanon, Algeria, Croatia, Serbia. Armenia, Scotland, Ukraine and New Zealand.” Impressive.

Coco also answered the question on everyone’s minds: which countries have so far been the best and worst in bed?

According to the adult star, Latinos are the most ‘intense’ in bed.

“My lovers from Brazil were the most enjoyable to be with,” she said.

“They were just up for having fun, whichever way it happens.”

Coco also revealed that men from more conservative countries are quite experimental when it comes to sex.

“Many of the conservative cultures enjoy the most ‘out there’ acts. For example, I have come across many Arab and Indian dudes who really like booty action in various forms,” said Coco.

As for the worst country in bed, apparently her most boring partners have been from Germany.

While they weren’t the best, Coco did praise German men being eager to please and how they apparently ask for feedback.

She also chatted to Australian radio hosts Kyle and Jackie O, where she shared what her experiences with Aussie men has been like.

“Australian men need to step it up a little bit,” she shared.

“You’re just not putting in any effort. And you need to wash your hands.”

Speaking of how much she loves a tradesman – a popular vocation in Australia – Coco encouraged guys to make sure they ‘scrub behind their fingernails’.

A fair point, if you ask me.

Entertainment

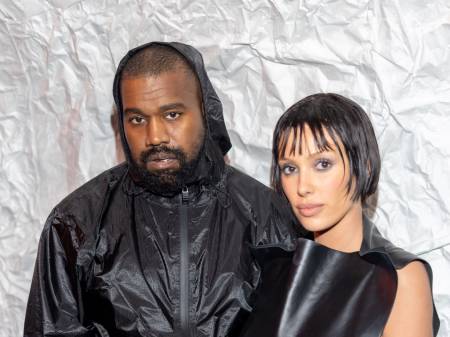

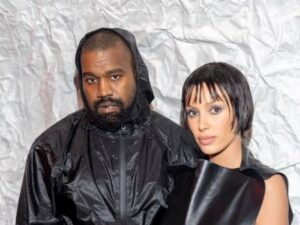

Kanye West Shares Provocative Video Of Wife Bianca In Bed And Fans Can’t Stop Pointing Out How Big It Is

It’s pretty common for Kanye West to post photos of his wife, Bianca Censori, and for fans to go wild over them.

The ‘Golddigger’ rapper has shared a lot of pictures and videos of his Australian wife.

These range from her daring, barely-there outfits to her strange, all-in-one body stockings.

Kanye is also known for making bold comments to get attention, like speaking out against critics.

Recently, the couple has stirred up even more buzz with a new social media post.

They shared a video from their bedroom, and there’s one detail that fans just can’t stop talking about.

On Instagram, Kanye posted a video showing Bianca lying on a bed surrounded by pillows.

She was dressed in all white, including white heels and a tight-fitting outfit.

It looked like she was on her phone, not paying much attention to Kanye, who was breathing heavily behind the camera.

The fans overlooked Bianca’s outfit and focused on the enormous size of the bed she was on.

It looked twice the size of a Super King bed, with enough room for more than five pillows.

One fan commented, “Bed can fit 5 [families] with 6 individuals.”

Another added, “It’s gotta be a nightmare trying to find a fitted sheet for that!”

A third fan mentioned that the huge bed resembled the one from Kanye’s 2016 music video for ‘Famous’.

Kanye soon deleted the video without giving any reason.

Even though the video is no longer available, Kanye is no stranger to sharing provocative content featuring his wife, whether in revealing outfits or suggestive poses.

Bianca seems to be on board with her husband’s posts.

However, not everyone is thrilled, especially her father, who has previously voiced his concerns about the content.

According to a source speaking to DailyMail.com, Bianca’s father, Leo, has asked Kanye to meet with him to talk about the explicit content being shared.

The source said, “Kanye has been invited to go to Australia, and Bianca is hesitant to allow this to happen because she knows how her father will react.”

“Her dad still plans to have a sit-down with Kanye, and Leo will not be intimidated by Kanye’s power or control. No one is expecting this to be all rainbows and family portraits.”

Despite this, Bianca is reportedly more than happy to go along with her husband’s ideas.

An insider told PageSix, “People are confusing Bianca’s creativity. She is a phenomenal personality, a phenomenal actor, who can entertain the public.”

“She’s a performance artist. Bianca is as much a performer as Ye is.”

Bianca and Kanye have been married since 2022, following Kanye’s high-profile split and divorce from his ex-wife, Kim Kardashian. Kanye has four children with Kim: North, Saint, Chicago, and Psalm.

Trending

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoJohn Wayne’s son speaks on military service, Hollywood life and his dad, ‘The Duke’ – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago40 Legendary John Wayne Quotes – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoNew biography reveals the real John Wayne – My Blog

-

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years agoWhy one POPULAR ACTOR was FIRED from THE SONS OF KATIE ELDER and lost his career as a result! – Old western – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoRio Lobo (1970) marked the last collaboration between John Wayne and Howard Hawks. – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoJohn Wayne and the ‘Bonanza’ Cast Appeared in This Epic Coors Light Commercial – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoHow Maureen O’Hara Broke Her Hand During Iconic Scene With John Wayne – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoDid John Wayne really have a good time filming 1972’s The Cowboys? – My Blog