Both the house and the man are smaller than you would expect, a result of the diminishing effects of old age that come to us all, if we are lucky enough to live that long. Kirk Douglas, now 100 years old, and Anne, his wife of 62 years, moved into the small bungalow in Beverly Hills about 30 years ago when they downsized from the multiple mansions where they had entertained friends such as Fred Astaire, Lauren Bacall and Ronald Reagan while Frank Sinatra knocked up Italian meals in their kitchen. But if their current home looks unprepossessing from the outside, there are extraordinary treasures within: a Roy Lichtenstein, personally inscribed to Douglas, hangs in the front hallway, while a Picasso and Robert Rauschenberg hang in the living room. The house is filled with modern masterpieces, a testament to the riches accrued by the man originally known as Issur Danielovitch – born so poor that he regularly went hungry until his mid-20s – through his own talent and self-forged toughness.

Kirk Douglas at 100: a one-man Hollywood Mount Rushmore

When Douglas himself enters the living room, he is leaning on a walker and accompanied by one of the various nurses who care for him and his wife around the clock. There is no question that reaching your centenary takes it out of a man: every movement suggests effort. Most frustrating for him, his tongue hangs heavy in his mouth, the result of a stroke in 1996, and the once-ringing diction is now slurred. Yet to judge the interior by the exterior proves to be a mistake. When Douglas starts talking not even the muffling layers of age can hide his still charmingly boyish personality, even if his body occasionally lets him down. He is, he says, “a little tired today”, but he makes sure to look a lady straight in the eye when he smiles.

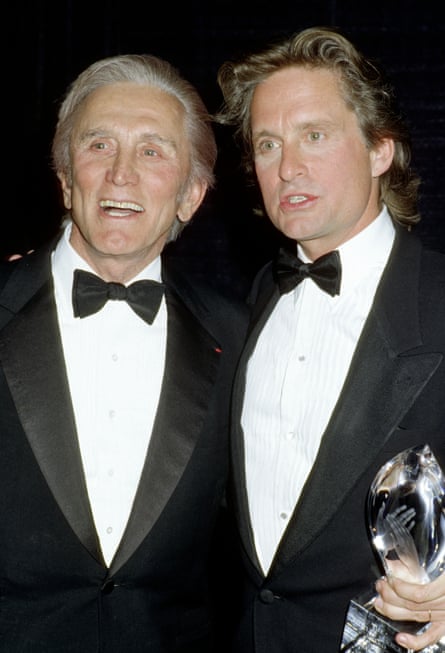

“How do I feel in general? Ahh,” he says, with a decidedly Jewish shrug, and during our time together he asks, anxiously and often: “Do you understand what I’m saying?” I do, mostly. That famously pugnacious chin is a little receded, but those familiar close-set eyes, which he passed on to his eldest son, Michael, are bright. Michael, as it happens, is currently staying in the guesthouse by the pool, visiting for a few days, as he does every month. “He comes to visit the old man,” Douglas says with pride.

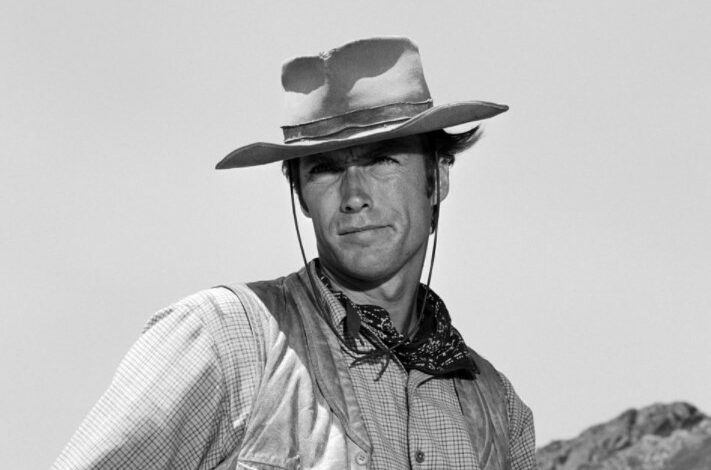

Douglas (right) with John Wayne in the 1967 film The War Wagon. Photograph: Archive Photos/Getty Images

Douglas (right) with John Wayne in the 1967 film The War Wagon. Photograph: Archive Photos/Getty Images

“I never, ever thought I would live to be 100. That’s shocked me, really. And it’s sad, too,” he adds.

There are so many friends he misses, the downside to being the last legend standing from the golden age of Hollywood.

“I miss Burt Lancaster – we fought a lot, and I miss him a lot. And John Wayne, even though he was a Republican and I was a Democrat,” he says.

Wayne was similarly fond of Douglas – they made a handful of movies together – but he was a little baffled by him. In The Ragman’s Son, one of Douglas’s several beautifully written memoirs, he recounts that Wayne attended a screening of Lust for Life, Douglas’s heartfelt 1956 biopic of Vincent van Gogh, and was horrified.

“Christ, Kirk! How can you play a part like that? There’s so few of us left. We got to play strong, tough characters. Not those weak queers,” Wayne said.

“I tried to explain: ‘It’s all make-believe, John. It isn’t real. You’re not really John Wayne, you know.’ He just looked at me oddly. I had betrayed him,” Douglas writes.

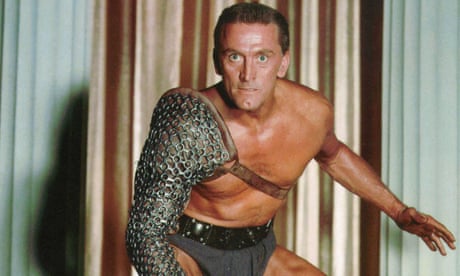

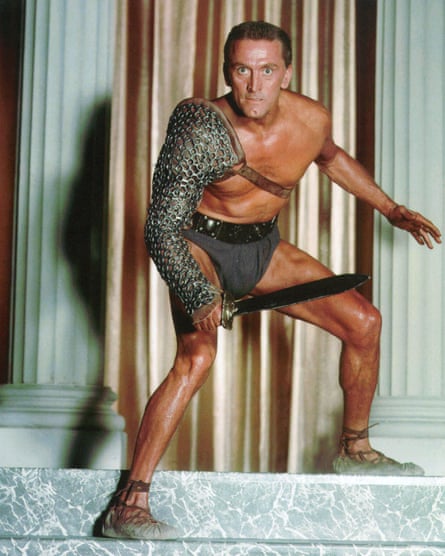

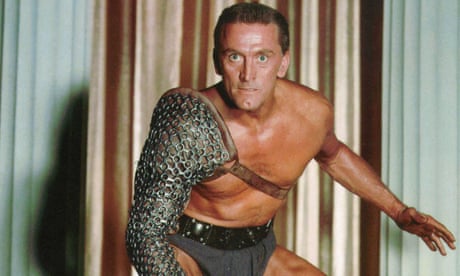

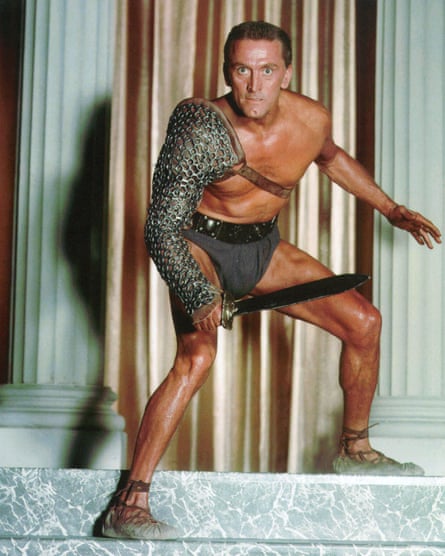

Douglas as Spartacus in 1960. Photograph: Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy

Douglas as Spartacus in 1960. Photograph: Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy

It is understandable that Wayne would see Douglas as a fellow tough guy: built like a small angry bull and with the furious focus to match, he was perfectly cast in films such as 1949’s Champion as the ambitious boxer Midge Kelly, and 1962’s Lonely Are the Brave – still Douglas’s favourite – as a noble cowboy. His reputation offscreen as a stubborn so-and-so who would fight with everyone from Stanley Kubrick to Otto Preminger contributed to this image. But Douglas was always more interested in what lay underneath. His acting theory, he has written, was “when you play a weak character, find a moment when he’s strong, and when you play a strong character, find a moment when he’s weak”. You can see this in his best performances, such as 1951’s Ace in the Hole, directed by Billy Wilder, in which he played an amoral journalist who realises too late he has gone too far, and also, of course, in 1960’s Spartacus, in which he gave humanity to a legendary hero.

To watch Douglas’s performances now, some of them more than 70 years old, it is striking how modern he seems, often more so than many of his contemporaries, who now look rather stagey. Douglas, with his famously intense stare juxtaposed with his relaxed delivery, looks like the precursor to Tom Cruise at his best. “I was not a tough guy [in real life],” he laughs. “I just acted like one.”

Never did he need more of this toughness than when he famously, if not quite single-handedly, broke the Hollywood blacklist (whereby those thought to have communist sympathies were denied work in the entertainment industry). The story has been told often: Douglas hired the blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo for Spartacus.

Douglas and his wife Anne in 2013. Photograph: Maury Phillips/WireImage

Douglas and his wife Anne in 2013. Photograph: Maury Phillips/WireImage

“It was that movie,” he starts, but then trails off, unable to remember the name of his most famous movie. Getting old really is a bitch.

“Spartacus! Yes,” he says, back on track.

Wasn’t he scared that he might be destroying his own career?

“No!” he scoffs. “It would have been very different if I’d been older, but I was stubborn then.”

When Douglas arranged for Trumbo to have a parking pass on the studio lot under his own name, and then included Trumbo’s name in the film’s credits, the blacklist was effectively broken. Some, including Trumbo’s family, have said Douglas has glorified his role a little in his frequent retelling of the tale. When Douglas published a book on the subject, I am Spartacus: Making a Film, Breaking the Blacklist, Trumbo’s daughter, Melissa, said she “threw it across the room”. But whatever the full truth, there is no doubting Douglas’s courage in letting himself be the public face of the blacklist rebellion.

So, given his famously liberal politics and abhorrence of political bullies, what does he think of the new US president? He reels back as if I’d smacked his cheek.

“That’s an unfair question,” he says.

Too cruel to ask that of a lifelong Democrat?

“Let’s just say I didn’t vote for him,” he replies.

Kirk and Anne Douglas at Golden Globe awardsin 1957. Photograph: Bettmann Archive

Kirk and Anne Douglas at Golden Globe awardsin 1957. Photograph: Bettmann Archive

Douglas, born when Woodrow Wilson was president, was one of seven children and the only son of illiterate Russian Jewish immigrants. He grew up speaking Yiddish at home in Amsterdam, New York in almost unimaginably deprived circumstances; the family’s income came from Douglas’s father’s daily attempts to sell scraps from a horse and buggy. Douglas fought his way out of his circumstances with his wit and wiles: he talked his way into a college scholarship and then baggsied another for acting school in New York, where he became lifelong friends with another Jewish student, Betty Perske, later better known as Lauren Bacall. Along the way, he had to contend with an enormous amount of antisemitism. When he started to become successful in Hollywood, he was invited to join an exclusive tennis club. The actor Lex Barker warned him at the time: “Of course, Kirk, you understand we can’t run a club the way we do back east. Here we have to let in a few Jews.”

“I am a Jew,” Douglas snapped back: he shed his Jewish name early on, but not his roots. Today, a mezuzah is affixed to the frame of his front door, and he credits his Jewish sense of responsibility for the fact that he has became one of the most generous philanthropists in Hollywood (he recently donated a further $50m (£40m) to, among others, his old college, St Lawrence University, to help students from minority backgrounds.)

Yet, Douglas has said that it is too simplistic to say, as many have done, that his childhood toughened him up. It was the reverse, if anything. If he seemed like a hard-ass when he was younger, it is because he was overcompensating: he was well into middle age before he stopped seeing himself as the scared and bullied little boy he once was, and his famous womanising, he thinks, was part of that. He had, he writes, “a mother complex”: “I constantly sought from the women around me a mother substitute.” His search certainly was constant: from Rita Hayworth to Marlene Dietrich, it is hard to name a famous actress from the mid-20th century who wasn’t seduced by Douglas. At one point he fretted to his analyst that he thought he might be impotent after a disappointing encounter the night before.

Douglas as Midge Kelly in the 1949 film Champion. Photograph: Bettmann Archive

Douglas as Midge Kelly in the 1949 film Champion. Photograph: Bettmann Archive

“You tell me that you had sex 29 nights in a row with different girls. On the 30th, you say you’re impotent,” his doctor replied drily. “You know, even God rested after six days.”

Douglas has been married twice, first to Diana, with whom he had Michael and Joel, and then to Anne, with whom he had Peter and Eric. But it took a while for matrimony to break his stride.

“I was a bad boy,” he admits, a little sorrowfully. “But Anne knew how to handle me.”

Indeed. Even before they married, Anne invited all the women she knew he had slept with to a party for him in Paris. “I couldn’t believe it when I walked in and saw the guests,” he says, laughing. “Ah! She knows everything.”

In his multiple memoirs, he writes with self-flagellating frequency about how his distant father let him down and how he feels he in turn let down his four sons.

Douglas with son Michael Douglas as a young boy. Photograph: Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images

Douglas with son Michael Douglas as a young boy. Photograph: Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images

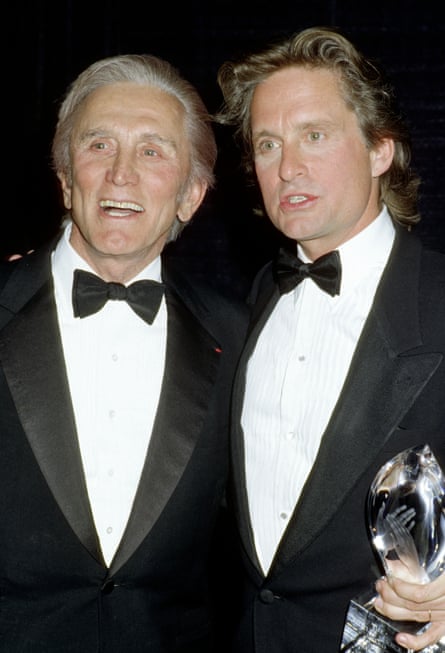

“I am so proud of Michael because he never followed my advice. I wanted him to be a doctor or lawyer, and the first time I saw him in a play I told him he was terrible,” Douglas laughs. “But then I saw him a second time and I said: ‘You were wonderful!’ And I think he is very good in everything he’s done.”

Did he ever feel competitive with Michael?

“No! Only proud,” Douglas insists. This isn’t totally true. He was, he admits, a tough father, one who wouldn’t even let his son win a race in the pool when he was 45 and Michael was 16.

“Geez, Dad, you were so tense, so uptight,” Michael recalled in adulthood.

“Michael didn’t like me much after his mother and I got divorced. It was only when he started acting that we became close,” Douglas says regretfully.

This is also almost certainly an exaggeration – Douglas’s books are full of stories that suggest a lifetime of closeness between him and his boys – but Michael certainly found a way to assert himself when he started acting. For years, Douglas’s dream film project was One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, but he could never get it off the ground.

“So Michael asked me if he could try to produce it, and I said: ‘Sure!’ Next thing I know, he has a director lined up and it’s all go. So I said to him: ‘Great! When do we start rehearsing?’”

“Not you, Dad,” his son replied, devastatingly. “You’re too old.”

“I couldn’t believe it!” Douglas says, eyebrows shooting up into his hair. “So I said: ‘Who’s playing my part? Jack Nicholson? Never heard of him. Well, at least it will be a flop …’”

Douglas with son Michael in 1988. Photograph: Ron Galella/WireImage

Douglas with son Michael in 1988. Photograph: Ron Galella/WireImage

By the 1980s, when young women approached him, it was no longer because he was Kirk Douglas but because he was Michael Douglas’s father. He laughs about this now, but I suspect that, for the once legendary swordsman, it stung a little at the time.

Michael Douglas is probably the most shining exception to the rule that children of famous actors rarely end well if they try to follow in their parents’ footsteps. “[Celebrities’] children, surfeited with every indulgence, are having miserable childhoods. The daughter of a television personality jumps out a window. A movie star’s son shoots himself. Why? To the rest of the world it looks as if these kids were brought up with everything,” Kirk wrote in 1988. Over the next two decades, he would have all too many occasions to ask himself this sad question. His youngest son, Eric, who had acted a little and struggled with addictions for years, overdosed and died in 2004 at the age of 46. Today, when talking about his sons, Kirk can’t quite bring himself to say Eric’s name.

Did Douglas ever find an answer to his question?

“Hollywood is make-believe, and that’s confusing,” he says, but he is starting to drift and tire.

History seemed as if it was repeating itself when Michael’s oldest son, Cameron, who had also tried acting, was arrested a few years after his uncle’s death on drugs charges. He was released last year after seven years of incarceration.

“Cameron is OK. He is doing so much better now and he says he will come visit next month. He’s working on a book, you know,” Douglas says, perking up. Douglas himself has just published his 12th book, Kirk and Anne: Letters of Love, Laughter, and a Lifetime in Hollywood, a collection of letters between the couple during their marriage.

Douglas with Burt Lancaster at a rehearsal for the Academy Awards in 1959. Photograph: NBC/NBC via Getty Images

Douglas with Burt Lancaster at a rehearsal for the Academy Awards in 1959. Photograph: NBC/NBC via Getty Images

Not bad to still be publishing at the age of 100, I say.

“Yes, that’s right,” he agrees, stoutly.

One of the most frustrating things about getting older, he says, is how out of touch he feels. “I don’t know who any of the new stars are, and they probably don’t know me,” he says.

Oh, I bet they know you, I say. That makes him smile: “Well, maybe …”

Surely he’s happy he was a star back in the golden age, not now when Hollywood is all about special effects and sequels. He nods vigorously. “Yes, yes. I was so lucky. Now it’s all different. Yes, very, very lucky.”

He asks if I mind if we stop now as he is getting weary, and, of course, I say no, although I wish we could talk all day. He gets up slowly, and with some assistance. But before he disappears he pats my arm and looks up at me.

“We’ll talk longer next time,” he promises.

I can’t wait.

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Douglas (right) with John Wayne in the 1967 film The War Wagon. Photograph: Archive Photos/Getty Images

Douglas (right) with John Wayne in the 1967 film The War Wagon. Photograph: Archive Photos/Getty Images Douglas as Spartacus in 1960. Photograph: Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy

Douglas as Spartacus in 1960. Photograph: Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy Douglas and his wife Anne in 2013. Photograph: Maury Phillips/WireImage

Douglas and his wife Anne in 2013. Photograph: Maury Phillips/WireImage Kirk and Anne Douglas at Golden Globe awardsin 1957. Photograph: Bettmann Archive

Kirk and Anne Douglas at Golden Globe awardsin 1957. Photograph: Bettmann Archive Douglas as Midge Kelly in the 1949 film Champion. Photograph: Bettmann Archive

Douglas as Midge Kelly in the 1949 film Champion. Photograph: Bettmann Archive Douglas with son Michael Douglas as a young boy. Photograph: Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images

Douglas with son Michael Douglas as a young boy. Photograph: Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images Douglas with son Michael in 1988. Photograph: Ron Galella/WireImage

Douglas with son Michael in 1988. Photograph: Ron Galella/WireImage Douglas with Burt Lancaster at a rehearsal for the Academy Awards in 1959. Photograph: NBC/NBC via Getty Images

Douglas with Burt Lancaster at a rehearsal for the Academy Awards in 1959. Photograph: NBC/NBC via Getty Images

John Wayne | Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

John Wayne | Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images