Clint Eastwood

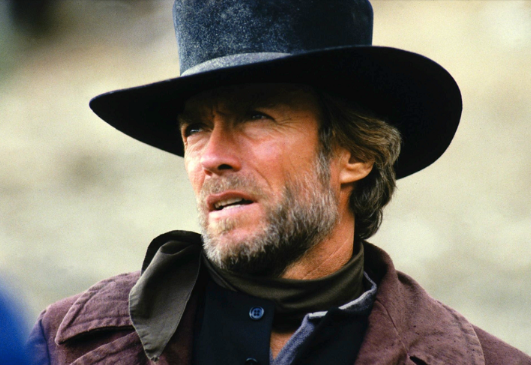

Pale Rider: Clint Eastwood saddles up one more time as the archetypal mysterious stranger in this mystical Western

Pale Rider(1985), directed by and starring Clint Eastwood, is a mystic Western where Eastwood reprises his iconic role as the mysterious loner, perhaps, for the last time.

“Who are you? Who are you… really?”

A most absurd question to be posing at the archetypal “mysterious stranger” of the “Western,” who rides in from infinity and would eventually ride off into infinity; the question becomes even more pointless, if this stranger has the grizzled face and the towering figure of Clint Eastwood; Clint may not have originated the character of the mysterious stranger: who rides in from the infinite wilderness into a lawless land and sets about righting wrongs and establishing justice; and once when his work is finished, he would ride back into the wilderness from which he came from; but Clint is the Star\actor the modern audiences most identifies as the embodiment of this archetype; having taken it to the next level with his “Man with no name” act in Sergio Leone’s “Dollars” trilogy, and later in his own directorial ventures like High Plains Drifter. So when actress, Carrie Snodgress (playing Sarah Wheeler) poses this question (once again) to Clint Eastwood’s “stranger” in the film, Pale Rider(1985), we chuckle; The absence (or the ambiguity) of a past history and the nature of his present actions is what defines this character. In the film, Clint is once again (and perhaps for the last time) playing a variation of the mysterious, laconic, loner\stranger that made him a pop cultural icon. Clint, who has been called a lot of names as part of embodying this archetype – Joe, Manco, Blondie, Stranger, – is here referred to as the “The Preacher”: Bearded, wearing a tall stovepipe hat with his tightly buttoned frock coat, and a clerical collar, Clint’s preacher arrives in the midst of a group of “Panhandlers”; a community of small-time gold miners in carbon canyon at the end of the California gold rush. This community, living nearby a creek in Northern California, are being harassed and attacked by thugs working for a mining businessman, Coy LaHood (Richard Dysart), who owns a nearby small town that bears his name. Though this community have a legal claim to the land, LaHood hires thugs to try and get rid of them, that’s until the arrival of Clint’s mysterious drifter – referred to as The Preacher because of his appearance – who becomes the protector of the community. He arrived as if as an answer to the prayer of this 14-year old girl named Megan (Sydney Penny) whose dog was killed by thugs during an attack. He seem to appear magically at her doorstep, as she finishes reading the passage from the Bible that gives the film its title—“and I looked and beheld a pale horse: and his name that sat on him was Death, and Hell followed with him.” Though wearing a dog collar, and sweet and courteous to the members of the community, there is something threatening, deceptive and other-worldly about the Preacher. At first, only Megan’s mother, Sarah Wheeler (Carrie Snodgress) is suspicious of the preacher; and her suspicions persist even when she warms up to him, and even falls in love with him. It’s then that she poses the above question to him regarding his real identity. After being repeatedly asked this question, the preacher nonchalantly replies “Well, it really doesn’t matter, does it?” , and she concurs “No, it doesn’t“; as long a he shows his worth and willingness to do the right things, that’s standing up to the thugs who work for LaHood and protect her, her daughter and the little community, nothing else matters. As opposed to Clint’s earlier films to feature this character, the preacher remains anti-violent and anti-Guns right up until two thirds of the film; he is forced to take violent measures in the initial portions as well, but it is never with a gun, he uses hammers and Hickory sticks for the purpose.. Also, still very laconic, he is not cold, amoral or self-centered as he was before. These are minor, but significant tweaks made to the character.

Apart from tormenting the miners, LaHood is also “raping” the land , so to speak, by using heavy hydraulic machines for the process of strip mining. On the miners’ side is Hull Barret (Michael Moriarty), a homesteader, who is Sara’s beau; Sara was abandoned by her husband and Megan is her daughter from that marriage. Hull is instrumental in uniting the community against LaHood; when LaHood offers them thousand Dollars each for giving up their claims, the miners turn it down at Hull’s insistence. LaHood has in his pocket a corrupt Marshal named Stockburn (John Russell), and his six deputies, who are good at taking care of “business”, like the elimination of the small-time miners from the canyon. Stockburn seems to know “someone” who answers to the description of the preacher, but he is sure that “someone” is dead and buried. The preacher too seems to know a lot about Stockburn, and maybe they had a run-in in the past in which the Preacher was badly burnt, and now he is looking for retribution. Preacher soon sheds his “pastoral” appearance and remerges as a gunslinger, and in a series of strange and violent confrontations, the Preacher kills Stokburn and his deputies and destroys LaHood’s empire, thus helping the homesteaders achieve peace. Now that his work is finished, and despite Sara’s love and Megan’s adoration of him, he rides off by himself into the sunset.

As it is obvious from the above description, Pale Rider will not win any prizes for originality. Everything in the film is a derivative of something that came before in this genre, most of them from Clint Eastwood films themselves. But as the eminent French critic and filmmaker Godard said: “It’s not where you take things from – it’s where you take them to.” that’s more important, and this film is a perfect example of how you can take something that’s totally unoriginal and fairly predictable, and still make something engaging and entertaining out of it. Though neither mentioned anywhere in the film’s credits nor mentioned by reviewers at the time of its release, the film is definitely a loose remake of George Stevens’ 1953 classic, Shane; Pale Rider is Shane as filtered through the iconography of Leone’s “Man with no Name” and the metaphysics of High Plains Drifter and provided with an environmental spin. Shane detailed the struggles of homesteaders against the rampaging cattle barons, with Shane, an angelic gunslinger played by Alan Ladd, arriving to protect the homesteaders. Replace homesteaders with Pan-handlers and cattle barons with Mining barons and you get this film’s scenario. Just like Marshal Stockburn, in Shane, there is a vicious killer named Jack Wilson (played memorably by Jack Palance) hired by the barons. There are two scenes in Pale Rider that exactly mirrors the scenes in Shane. First is the scene where hull and the preacher break up a giant boulder with hammers, and the second is the very last scene where Megan says goodbye to the preacher, which is very reminiscent of the famous last scene in Shane, where the boy, Joey, bids farewell to Shane , and his voice echo back from the mountains. Also, the gender reversal of turning the boy Joey, who hero-worships Shane to the girl, Megan, who adores and falls in love with the preacher adds another level to the film, as both mother and daughter fall for the Preacher. What is interesting is how the preacher deals with this; He does not succumb to the opportunity from the beautiful 15 years old daughter who is willing to submit to him fully, but it is hinted that Preacher does go to bed with mother, Sara. It’s an extension of the theme portrayed in Shane, where there is a silent romance going on between Shane and homesteader, Van Heflin’s wife, played by Jean Arthur. It adds another fascinating element which lifts the film from being just an obvious western. The theme of an underage girl falling in love with the much older Clint character was earlier explored in another Clint movie, The Beguiled(1971). Also, the theme of both mother and daughter falling in love with the same man was explored in another Western, Robert Aldrich’s The Last Sunset, where Kirk Douglas falls in love with the characters played by Dorothy Malone and Carol Lynley, and in the end it is shockingly revealed that Lynley’s character is Douglas’ daughter. Clint also borrows from his mentor Sergio Leone, in the way Marshal Stockburn and his deputies are portrayed; dressed in long dusters and moving around robotically, they resemble Henry Fonda and his henchmen from Once upon a time in the West. The climax of the film is very reminiscent of Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon, where an upright Marshal (Gary Cooper) takes on 3 outlaws in a deserted town all alone; here it is flipped to show the lone stranger taking on the corrupt marshal and his deputies. In the film, when the preacher appears for the first time, he is seen coming to the help of Hull, who is being bullied by Lahood’s thugs. The preacher is not carrying his guns and he uses a Hickory stick, like a sword, to deal with four bullies, and it looks like a homage to a famous scene in Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, where Toshiro Mifune’s mythical samurai takes down 4 goons, with just a few sweeping movements of the sword; Clint, of course played the same Mifune character in an unofficial remake, A Fistful of Dollars, which became his first film with Leone. Obviously, these are all subtle tweaks and homages that Clint has incorporated as part of refreshing the formula and keeping the film interesting, and it does work. Sometimes it’s the way the filmmaker brings new inflection to old stories that reveal his highest qualities. At the time, Clint was attempting to save the Western genre, and perhaps this was also his way of reminding the audiences of the great films of the past.

Regarding the supernatural elements of the film, unlike High Plains Drifter, where the supernatural element was rather overt and the style of the film was more baroque, here it is more subtly handled and the film is made in a more classical tradition. Also, in “Drifter“, the hero was brazenly amoral: raping, looting, displacing and killing the townsfolk whom he was suppose to protect; the townsfolk themselves are an immoral and conniving bunch, but here the hero and those he is protecting are portrayed in the most “traditional” way: the hero is virtuous without a fault and the community is weak and helpless and made up of only good people. The main mystical element in the film is regarding the arrival of the Preacher: is his arrival a pure coincidence?, is he an angel sent to help them? or a murdered man who returns as an avenging angel?. It is this side of Pale Rider which makes it more than just another western. Add to that Clint’s trademark “dark humor” and his immense gracefulness as a filmmaker that enables him to glide through the more complex scenes without being flashy or pretentious, and you get a superior film that holds the viewers attention at all times. He does not spell everything out, just leave it to the viewers to decide. There are hints dropped throughout the film as to the possibility of the Preacher having returned from beyond the grave to avenge his death; we see six bullet holes on his back, bullets have pierced through the vital organs that would have made it impossible for any recipient of those bullets to survive. Another cinematic technique that’s used throughout is the sudden appearance and disappearance of the preacher in a frame; we see the preacher from the POV of a character in the film, then the camera cuts to the viewer looking at the Preacher and then, when the camera cuts back to the preacher, he is not there anymore. But the biggest hint to the preacher’s metaphysical existence is given in the climactic gun duel between Stockburn and the Preacher; as opposed to other gunfights where the fighters draw on each other from at least a block apart, here the preacher walks right up to Stockburn and stands at his arms length before he delivers the coup de grâce. Stockburn too recognizes the Preacher as “someone” from his past, before the preacher pumps 6 bullets into him, exactly the same bullet count we saw on Preacher’s body. The entire sequence makes it appear as if the Preacher is a supernatural force that has gone right through Stockburn. In an interview, Clint did claim that the preacher is an “out and out” ghost, though in the film there are also scenes where he is seen doing non-ghostly things; i don’t know whether ghosts have to go into bank vaults to retrieve their six shooters. I was also very intrigued by the Preacher’s weapon of choice: he carries a “Remington 1858 New Army” with a cartridge conversion as his sidearm, and carries several pre-loaded cylinders to use like a modern speed loader. So he does not load his bullets one by one as was the practice then, but he just uses the cylinders to load and fire quickly, like they do in modern guns. I don’t think i have seen this in any other Western. Also, throughout the lengthy climax, Clint makes a big show of this gun: he shoots extreme close-ups of Preacher’s hand holding the gun, removing and loading cylinders and getting it ready for the next round of action, and this is repeated again and again like a ritual. I found it very intriguing and felt that this whole business with the gun accentuated his mystique.

When Clint embarked upon making Pale Rider, the “Western,” as a genre was dead in the water, and the person most responsible for its death was Clint’s protégée, Michael Cimino. Cimino had written the script for the “Dirty Harry” film, Magnum Force(1973) and made his directorial debut with Clint starrer, Thunderbolt and Lightfoot(1974) . Though the Western was slowly dying out through the 70s, it was Cimino’s “auteurism ran rampant” 1980 Western, Heaven’s Gate‘s massive failure that put the last nail in the Western’s coffin. As with any big success or failure, Hollywood learned all the wrong lessons from the Heaven’s Gate’s debacle; one of them being that Western is finished, which was rather funny, because Heaven’s Gate was not a conventional Western at all; it was a revisionist take, with very little plot or characterization, and a most unheroic Western hero at the center of whatever Narrative it had. But the fact remains that nobody attempted to make a decent western for almost 5 years after that catastrophe. So it fell upon the last Western hero standing; the greatest living Western Legend at the time, Clint Eastwood, to resurrect the one true American genre. This was the only film that Clint committed to making without ever seeing a script, he only had a few ideas which he bounced off with the writers. He was sure that, given a well made traditional Western, which deals with contemporary issues, the audiences will come. He was vindicated by the success of this film; Clint’s films are all very efficiently and economically produced . This film cost just about $7 million, which was a very modest sum, and compared to Heaven’s Gate that cost $44 million, a trifle. The film returned close to $45 million, thus making it an extremely profitable venture.

As actor and director, the film finds Clint in top form; by then Clint’s acting style was fully developed, and especially in these kinds of roles, it had been carefully perfected over the course of two decades; that Mount Rushmore face was now grizzled and balding, those hoarse whispers, those long pauses, those squinty eyes, that wry smile; each of them work as significant tools in conveying the essence of this character, or rather this archetype. Nobody knew what was good for Clint Eastwood, the actor, more than Clint himself; he was fully aware of his strengths and weaknesses, and that’s why he truly blossomed as an actor under his own direction. Clint is not called upon to do anything extraordinary or out of the box here as a performer, as opposed to his next (and more) revered Western, Unforgiven(1992), where he completely played against type; he just has to be himself. His natural coolness forms the basis for the character. He has the ability to limit his dialogue and communicate to the audience with minimal body language, and above all, he just needs to exist, merely just be present in a scene to make his presence felt. He has accumulated such a legend by then, especially as a hero of Westerns, that he naturally brings all that backstory and heft to the character. As a director, he has given a haunting feel to the film as it relates to the Preacher’s mysterious presence. It’s also a nicely contained film, simply darting between the camp and the small town, which always seems deserted and spooky further adding to the mystic feel. Clint is helped immensely by Lennie Niehaus’ wonderful orchestral score that mixes foreboding string arrangements with more bombastic music, especially drums for the climax portions; some themes have been recycled from High Plains Drifter’s eerie theme music. Cinematographer Bruce Surtees, in his last collaboration with Clint, provides some gorgeous visuals of the outdoors, but the interiors looks intentionally underlit. Clint always complained about the old Westerns (like Shane) where the interiors of homesteads seems to have a lot of light, i guess, he deliberately wanted to create a contrast. It also allows to amplify the mysterious quality of his lead character. The film was shot on various locations in Idaho such as the Boulder Mountains and the Sawtooth National Recreation Area as well a few scenes shot at Tuolumne County in California. Clint also shows his development as a great action director in the beginning and ending action sequences; the climax is particularly well composed, where he takes his time with the action, it develops very slowly and gain momentum, as the preacher stars dispatching one thug after another. The only main issue i had was with the casting of John Russell, who looks like a pale version of Jack Palance or Lee Van Clef; Russell has a history of playing the main villain opposite John Wayne in Rio Bravo(1959), but here he looks rather weak and too old, i wish he had gotten Palance to reprise that role. I wish the two main female characters were also better developed, they all seem to have been drawn from a “male gaze” and lacks depth. Also, at 116 minutes, the film is a tad too long, there are times when the pace flags, but overall, Clint creates a vivid and exhilarating Western that tells an age-old tale of a stranger helping out the helpless to fight off a gang of thugs, with some interesting tweaks here and there, even as it delivers all the expected western elements: the gunfights, the archetypal hero and the villains; the romance, great outdoors, etc.. Pale Rider does not immediately come up when great Westerns , or even great Clint Eastwood Westerns are discussed, and rightfully so; Unforgiven and The Outlaw Josey Wales are greater Westerns than this, but it is still a damn-good Western, and under the circumstances it was made – in an effort to resurrect the genre itself- it is a most successful one.

You may like

Clint Eastwood

Mystic River: Why Clint Eastwood’s Best Movie Still Holds Up Today

A filmmaker of Clint Eastwood‘s caliber is going to have a filmography full of gems. Primarily known for his work in Westerns, biopics, and military dramas, every so often, Eastwood steps outside his comfort zone and delivers in a genre that would seem completely unexpected on paper. That happened in 2003 with Mystic River, a neo-noir murder mystery drama that seems a bit forgotten or overlooked, even though it was a financial success and earned six Academy Award nominations. It represents Eastwood at his very best, breathing vivid life into complex characters as he examines a plethora of themes that range from loyalty, friendship, revenge, and, ultimately, forgiveness.

Mystic River is based on the 2001 novel of the same name by Dennis Lehane, and it follows the lives of three childhood friends, Jimmy Markum (Sean Penn), Sean Devine (Kevin Bacon), and Dave Boyle (Tim Robbins), living in Charlestown, Boston in 1975. Dave is kidnapped by two men claiming to be police officers, and he’s sexually abused by them over a four-day period until he escapes. The traumatic event shapes the three friends, and they ultimately lead very different lives twenty-five years later.

Jimmy is an ex-con that now owns a convenience store in the neighborhood, Sean works for the Massachusetts State Police as a detective, and Dave is your everyday blue-collar worker that still lives with the trauma of being abducted and raped. Their lives are forced together once again through tragedy when Jimmy’s daughter Katie (Emmy Rossum) is found murdered, and friendship is tested when all signs point to Dave being the murderer.

Mystic River Is a Departure From Clint Eastwood’s Other Work

Eastwood tackles the material in Mystic River with a sure and confident hand. It also represents a unique departure from some of his other films. Much of the action takes place under the cover of darkness, and Eastwood is able to find beauty in that darkness. The filmmaker focuses on a character’s eyes or the gleam of a weapon, for instance, as darkness permeates most of the scene.

For the scenes that take place during the day, the filmmaker opts for tight close-ups that linger over the emotions of his impressive cast. There is something uncomfortably intimate about Mystic River, and that has much to do with the subject matter. None of this story is particularly easy to digest, and Eastwood adds to that discomfort with his choices to frame scenes in such a way that’s almost intrusive. The audience feels a growing sense of dread and tension as more of the story unfolds.

Using Lehane’s novel and Brian Helgeland’s screenplay as a blueprint, Eastwood profoundly explores generational trauma and how the sins of the past can leave a permanent mark on our present. Even though the abuse only happened to Dave, the effects of the event leave a mark on all three friends, with Dave being the primary victim and the others feeling a sense of survivor’s guilt for not being subjected to it themselves.

The ordeal forever changes their union because they’re never quite able to look at each other the same way again, as each friend deals with the trauma differently. Jimmy is stunned by the act of abuse but can’t give Dave the support he needs, which then bleeds into their present when Jimmy begins to suspect that Dave had something to do with his daughter’s murder. He doesn’t want to consider that his friend would do something like this because of the trauma he endured as a child, but as evidence mounts against him, Jimmy has to decide if friendship and loyalty overshadow his need for vigilante justice. The story is rich with so many complexities that make it some of Eastwood’s most compelling work as a filmmaker.

Eastwood also takes his time with the story and lets it unfold as it should. Mystic River is very nuanced, and he knows he’s dealing with heartbreaking subject matter that requires patience and respect. The story is grounded in so much reality that Eastwood seems keenly aware that a viewer might be an actual victim of this kind of abuse themselves, so he delicately approaches the topic and gives it the emotional weight it deserves.

He also shows the uncomfortable side of abuse where the victim, unfortunately, can be shamed because of the event. Dave becomes an outsider later in his life, even with his close friends, something that sadly comes along with this kind of trauma. Eastwood approaches all of this responsibly and provides a very balanced outlook to all the events transpiring on screen.

Mystic River has become known for its powerhouse performances, and Eastwood pulls the very best from his ensemble cast. While the scenes with the young actors are brief in the beginning, they set the tone of who these people will be twenty-five years later. Dave becomes the outcast because of the event; Jimmy lacks empathy and doesn’t trust authority, while Sean becomes the grounded one of the bunch and a police officer in an attempt to prevent a tragedy like this from ever happening again.

Clint Eastwood Pulls Powerhouse Performances From His Cast

Tim Robbins, Sean Penn, and Kevin Bacon do a great job conveying the unspoken tension between all three of these characters. There is a sense of loyalty, but so much has taken place over the years that it has forced them all to lead very different lives. As a group, they are uniformly excellent. You feel the history between the characters and the bonds that were broken, only to be reopened by a new traumatic event.

On their own, Penn gives the performance of a lifetime as Jimmy, and it’s not a shock that this turn finally earned him his first Academy Award for Best Actor. Penn is a dominant presence in all of his scenes, and there is a sense of uncertainty whenever he’s around because you don’t know exactly what move he will make.

That’s not to say he doesn’t display layers. All of that bravado is broken once he finds out his daughter is murdered. It’s hard to pinpoint a director’s best scene on film, but what Eastwood pulls out of Penn during the “Is that my daughter?” sequence represents some of his very best work as a filmmaker.

Robbins also received an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his work here, representing a much-deserved win. As Dave, Robbins is the tragic and emotional heart of the story. The viewer feels instant empathy for Dave due to what he went through as a child, but you’re also left questioning everything when it seems like Dave could be the one who murdered Katie.

Robbins keeps you on your toes throughout, making you question his innocence while also seeing the tenderness in him as he interacts with his own child, who is just about the age he was when he was abused. As for Bacon, of the three male leads, he gives the most subdued performance, but it suits the character. He’s trying to make everything right and keep it all together. It’s a subtle performance that carries its own emotional weight.

Eastwood also makes the supporting roles worthy of attention. Marcia Gay Harding, as Dave’s wife Celeste, puts in powerful work here that earned her a Best Supporting Actress Oscar nomination, while Laura Linney more than holds her own with Penn as his second wife, Annabeth. In addition, Laurence Fishburne also fills in as Sgt. Whitey Powers in another excellent part.

Mystic River is a haunting and poetic motion picture that showcases a director laying it all out on the table. Eastwood gives the audience everything he has as a director and pours it out across the screen in a film that is just as powerful twenty years after its initial release.

Clint Eastwood

Clint Eastwood’s Most Iconic Non-Western Role Was Only Possible Because Of This Actor

SUMMARY

Clint Eastwood’s role in Dirty Harry is considered one of his most iconic, and the film is a classic in the crime genre.

Paul Newman initially turned down the role of Harry Callahan in Dirty Harry but recommended Clint Eastwood for the part.

Newman declined the role due to his liberal beliefs, and Eastwood’s portrayal of Callahan differed from Newman’s perspective, but both respected each other.

SCREENRANT VIDEO OF THE DAY

Although Clint Eastwood first built his impressive career on Western movies like The Man with No Name franchise and The Outlaw Josey Wales, the actor’s biggest non-Western role in Dirty Harry is one of his most iconic, and it might have never happened without this one actor. Clint Eastwood began acting in the 1950s, and over several decades, became a staple in the Western genre. What makes Eastwood stand out is the fact that he has not only appeared in countless films, but has also directed them himself. Films like Unforgiven and Gran Torino have defined his career. However, Dirty Harry is by far one of Clint Eastwood’s best films.

In 1971, Clint Eastwood starred in the neo-noir action film Dirty Harry. The film, and its adjoining sequels, follow Inspector “Dirty” Harry Callahan, a rugged detective that is on a hunt for a psychopathic serial killer named Scorpio. The Dirty Harry franchise lasted from 1971 to 1988, and has since been considered a classic. In fact, Dirty Harry was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress because of its cultural significance. However, this film might have been vastly different if Clint Eastwood had never been in it, and scarily enough, this definitely could have happened back in 1971.

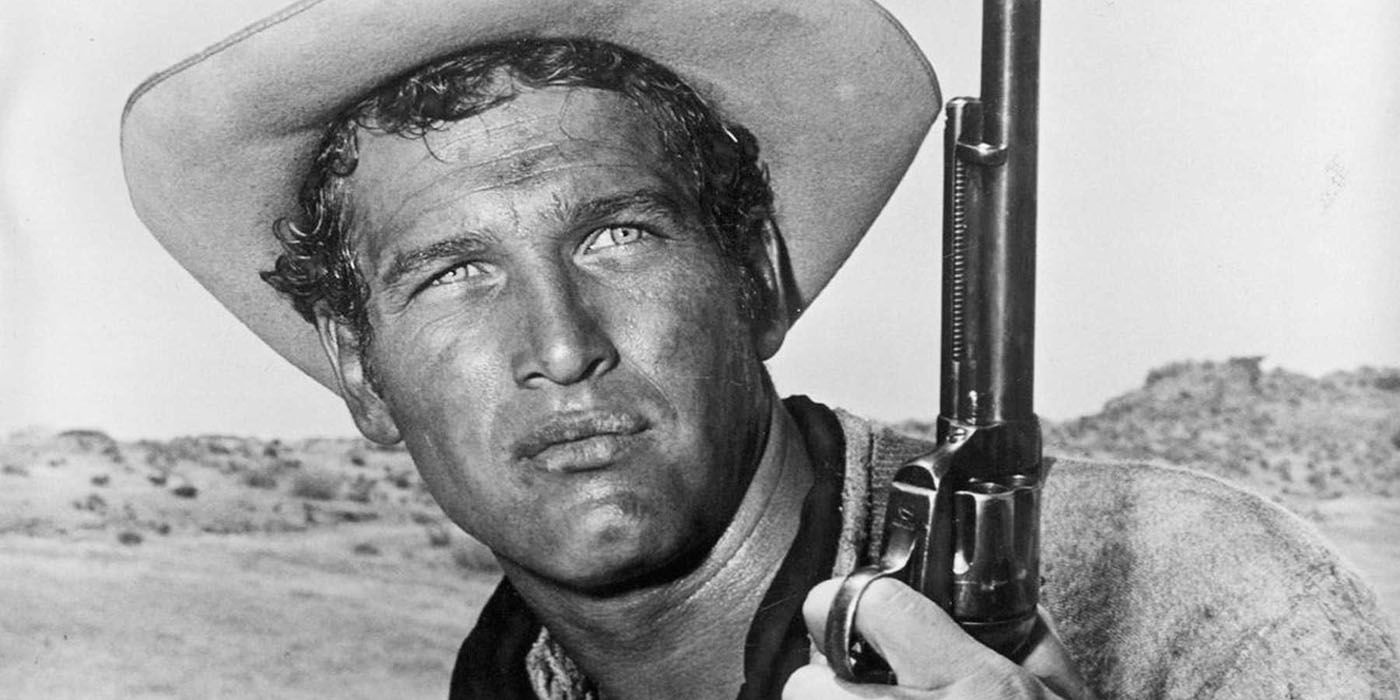

Paul Newman Rejected Dirty Harry Before Suggesting Clint Eastwood For The Role

Dirty Harry went through many production challenges before it was actually made, and one of those included casting the iconic detective. In the film’s early stages, the role was offered to actors such as John Wayne, Robert Mitchum, Steve McQueen, and Burt Lancaster. However, for various reasons, including the violence that permeates the film, these actors all declined. For a time, Frank Sinatra was attached to the project, but he also eventually left the production. In reality, Clint Eastwood wasn’t even in the cards for portraying Dirty Harry, but his big break came when Paul Newman was offered and declined the role.

Paul Newman, like many amazing actors before him, was offered the role of Harry Callahan, but ultimately said no. However, what makes his refusal stand out among the rest is that he recommended another actor that could be perfect for the role: Clint Eastwood. At this time, Eastwood was in post-production for his first film Play Misty for Me, meaning his career was taking something of a turn. Also, unlike his predecessors, Eastwood joined up with Dirty Harry, just as Newman thought he would. Because of his Western roots, the violence and aggression that made up Dirty Harry didn’t bother Eastwood at all.

Why Paul Newman Turned Down Dirty Harry

Paul Newman turning down the leading role in Dirty Harry may not seem too surprising considering the host of other actors that also declined the movie, but Newman definitely had his reasons. While previous actors had condemned the movie for its incredible violence and themes of “the ends justify the means,” Newman refused to take the role because of his political beliefs. Since Harry Callahan was a renegade cop, intent on catching a serial killer no matter the cost or the rules that would be broken, Newman saw this character as too right-wing for his own liberal beliefs.

Paul Newman was an outspoken liberal during his life. He was open about his beliefs, so much so that he even made it onto Richard Nixon’s enemies list due to his opposition of the Vietnam War. Other issues that Newman spoke out for included gay rights and same-sex marriage, the decrease in production and use of nuclear weapons, and global warming. As a result of his politics, Newman quickly denied the role of Harry Callahan. In an interview with Entertainment Weekly as reported by Far Out Magazine, Clint Eastwood commented that he didn’t view Callahan in the way Newman did, but still respected him as an actor and a man.

Would Dirty Harry Have Been So Successful Without Clint Eastwood?

Ultimately, it’s hard to say whether Dirty Harry would have been successful without Clint Eastwood. Arguably, any big-time actor could have made the film succeed solely based on their fame. However, one aspect of Dirty Harry and its carousel of actors is that the movie had various scripts, all with different plots. So, if Dirty Harry had been in a different location with a different serial killer and a different lead actor, there’s a chance it wouldn’t have been nearly as successful. In the end, Dirty Harry is a signature for Clint Eastwood, and most likely, audiences are lucky that it was made the way it was.

Clint Eastwood

The story of how Clint Eastwood prevented Ron Howard from embarrassment

A star of American cinema both in front of and behind the camera, Ron Howard is often forgotten when recalling the greatest directors of modern cinema, yet his contributions to the art form remain unmatched. Working with the likes of Tom Hanks, Chris Hemsworth, Russell Crowe and John Wayne, Howard has brought such classics as Apollo 13, A Beautiful Mind and Rush to the big screen.

Entering the industry in the late 1950s and 1960s, Howard started his career as an actor, making a name for himself in shows like Just Dennis and The Andy Griffith Show before his role in 1970s Happy Days would catapult him to national acclaim. His directorial debut would come at a similar time, helming 1977’s Grand Theft Auto, the ropey first movie in a filmography that would later become known for its abundance of quality.

Known for his acting talents, Howard wouldn’t become a fully-fledged director in the eyes of the general public until the 1980s, when he worked with Tom Hanks on 1984’s Splash and George Lucas for the 1988 cult favourite Willow.

With hopes of becoming the new Star Wars, Willow was instead a peculiar fantasy tale that told the story of a young farmer who is chosen to undertake the challenge to protect a magical baby from an evil queen. Starring the likes of Warwick Davis, Val Kilmer and Joanne Whalley, the film failed to make a considerable dent in pop culture at the time, largely being ridiculed by critics and audiences alike.

Screened at the Cannes Film Festival, the movie was spared humiliation by none other than Clint Eastwood, who saw the craftsmanship behind the picture, as described by Ron’s daughter, Bryce Dallas Howard.

Speaking to Daily Mail, the actor recalled: “My dad made a film called Willow when he was a young filmmaker, which screened at the Cannes Film Festival and people were booing afterwards. It was obviously so painful for him, and Clint, who he didn’t know at that time, stood up and gave him a standing ovation and then everyone else stood up because Clint did”.

Dallas Howard, who worked with Eastwood on the 2010 movie Hereafter, became very fond of Eastwood as a result, looking up to him as an exemplary Hollywood talent. “Clint puts himself out there for people,” she added, “As a director he is very cool, very relaxed, there’s no yelling ‘action’ or ‘cut’. He just says: ‘You know when you’re ready.’ I told my dad he should do that!”.

Take a look at the trailer for Howard’s 1988 fantasy flick below.

Trending

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoJohn Wayne’s son speaks on military service, Hollywood life and his dad, ‘The Duke’ – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago40 Legendary John Wayne Quotes – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoNew biography reveals the real John Wayne – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoWhy one POPULAR ACTOR was FIRED from THE SONS OF KATIE ELDER and lost his career as a result! – Old western – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoRio Lobo (1970) marked the last collaboration between John Wayne and Howard Hawks. – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoHow Maureen O’Hara Broke Her Hand During Iconic Scene With John Wayne – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoJohn Wayne and the ‘Bonanza’ Cast Appeared in This Epic Coors Light Commercial – My Blog

-

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year agoDid John Wayne really have a good time filming 1972’s The Cowboys? – My Blog