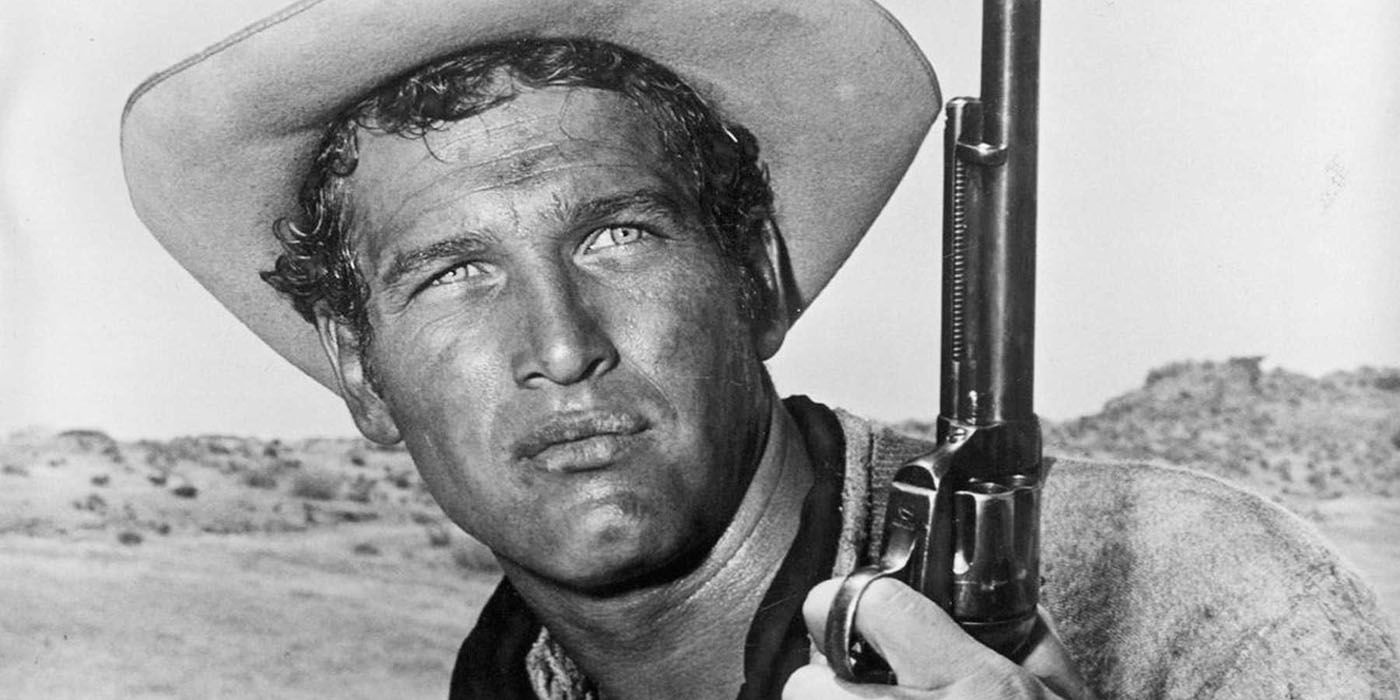

When hearing the name Clint Eastwood, there are a few different images that may pop into one’s head. His starring roles as the Man with no Name in Sergio Leone’s classic Dollars Trilogy or as antihero Harry Callahan in the Dirty Harry films are top contenders, both of which established him as one of Hollywood’s greatest action stars. For the directing side of his career, his Academy Award-winning work on Unforgiven and Million Dollar Baby would also be high up the list, as would his recent turn towards prestigious dramas with films like American Sniper or Sully. What probably wouldn’t crop into someone’s head, however, is a romance co-starring Meryl Streep about a man who photographs bridges for a living, and whose leisurely pace and soft-spoken aesthetic seems tailor-made for viewing on a Sunday afternoon.

The Bridges of Madison County might appear to be a million miles from Eastwood’s other work, but in practice it’s the perfect showcase for his talents as a filmmaker. Eastwood’s style of directing has always championed minutia over grandness, reveling in the moments that other directors may find inconsequential. Rather than opting for sweeping camerawork or lavish orchestra soundtracks that feel like they’re about to lift you off your feet, Eastwood has always been happy to keep himself at a distance, letting his actors take center stage. It’s an approach that stems from beginning his career in front of the camera rather than behind it, with Eastwood gradually developing his craft to quietly become one of America’s greatest directors, and nowhere is that more evident than The Bridges of Madison County.

Adapted from the Robert James Waller novel of the same name, the film tells the story of Francesca Johnson (Streep), an Italian war bride who lives with her husband and two children in 1960s America. After her family leaves town to attend a fair, she crosses paths with Robert Kincaid (Eastwood), a photographer for National Geographic who has come to photograph the county’s historic bridges. Francesca agrees to help him, and soon after the two begin an intense four-day affair. As established in the film’s present-day opening, this relationship does not last, with Francesca knowing she will ultimately return to her family, but it leaves a profound effect on them both that lingers for the rest of their lives. It’s a simple story, and its relaxed pace ensures the audience will have plenty of time to soak up their doomed romance. But, as with many masterworks, its brilliance comes not from the story itself but rather how it is presented, and it’s here that Eastwood’s talents shine.

The Bridges of Madison County is a film where very little happens. Now, obviously that is hyperbolic. Clearly things happen or there wouldn’t be much of a film to talk about, but the film lacks anything in terms of grand set pieces or large emotional moments which seem included only for its actors to get nominations at that year’s Academy Awards (not that that stopped Streep getting nominated anyway). Except that’s not true either. The Bridges of Madison County is a film where an entire tsunami of things occurs, it’s just that they’re little more than tiny droplets that a casual observer might carelessly brush aside. But what is an ocean if not a multitude of drops, and together they form one of the most powerful depictions of romance in cinema.

Where The Bridges of Madison County excels is in these smaller moments, an example of which can be seen when Francesca and Robert visit Roseman Bridge shortly after meeting for the first time. The sequence in question is rather simple, with Robert taking some test shots in preparation for the proper shoot the following day, but Eastwood’s quiet but efficient direction transforms it into something far more interesting. There’s a playful nervousness to the scene, with Francesca struggling to process the handsome stranger who has just waltzed into her life. From the way she is unable to keep her arms still (crossing and uncrossing them, rubbing them, touching her face with them, and finally pretending to swat imaginary flies with them), to how her entire demeanor subtly changes depending on if she’s in view of Robert or not. Shortly after Robert picks her a bundle of flowers, which he quickly drops when Francesca jokes that they’re poisonous. While gathering them back up, both have a moment when they gaze longingly at the other, but only when the other person isn’t watching. It lasts for a fraction of a second, but that’s all it has to be. With just a few frames Eastwood has planted the seeds of their romance, ready to sprout in the following two hours. It’s visual storytelling at its finest, and sets a precedent the rest of the film is more than happy to follow.

It’s moments like this that make The Bridges of Madison County the masterwork that it is, and what’s most impressive is how Eastwood sustains this throughout the film. The entire breadth of their relationship can be understood from their body language alone, moving from casual acquaintances to close friends to intimate lovers based solely on the brush of an arm here or an affectionate smile there. Not a second is wasted, and Eastwood’s stripped-back approach ensures all possible distractions are removed. There’s a cleanliness to how he utilizes the camera, with images free of all but the most essential ingredients, subtly guiding the viewer without ever making its presence known. The soundscape, a symphony of crickets chirping across the open plains of Iowa while ancient cars drive past on distant highways, sucks the viewer into its world. The film rarely uses music, and what little there is blends seamlessly into the background, existing only to add the final touches like sprinkles on an ice cream sundae. It’s a simple approach to directing, and you’d be forgiven for watching the film without ever consciously noticing any of these decisions, but that’s exactly the point. Eastwood films go to a lot of effort not to be noticed, but there’s a deliberateness to everything that can only be fully appreciated on a second watch.

This approach reaches its peak during Francesca and Robert’s final scene. Unable to abandon her family, Francesca returns to the mundanity of her previous life, but a love as powerful as the one she has just experienced is not something that disappears overnight. One afternoon, while sitting in her car and waiting for her husband to return from the shop, Francesca spots Robert standing on the sidewalk. He begins to approach, but stops. Instead he just looks at her, and she looks right back, and then he leaves. It’s an incredibly basic scene when just describing it, but its simplicity is exactly what makes it the film’s greatest moment. There’s no dialogue, no emotional outburst as one or both break down in tears, just the image of two ill-fated lovers staring at each other as rain beats down upon the world. The flicker of a smile they both share as memories of the past four days pour over them is one of the most heartbreaking images in cinema, and made all the more depressing by the way Robert just leaves straight after. The scene immediately after, where Francesca toys with her door handle as she debates running after him, all the while her husband remains oblivious to the emotional turmoil occurring right next to him, showcases Eastwood’s ability to make even the simplest of actions into moments of unimaginable tension. What other film has the act of opening a car door be the emotional crux that two hours of build-up have led to, let alone one that manages to pull it off flawlessly? It’s filmmaking in its purest form, with only the slight movement of a hand saying more than an entire monologue ever could. It might not have the flair of a typical Clint Eastwood action scene, but its understanding of the medium’s strengths remains identical.

But at the end of the day, what really is the difference between a shootout in the Wild West and two lovers saying goodbye in the American Midwest. On a fundamental level they’re both nothing more than scripted movement, captured by a camera and then arranged on an editing timeline for the sake of an audience. The celebration of movement is what defines cinema, with the camera allowing us a close-up view at the most intimate of moments in a way other mediums cannot replicate. The Bridges of Madison County, much like all of the films directed by Clint Eastwood, delights in this belief. It’s a film that effortlessly translates its source material from page to screen, transforming its story to fit the new medium without ever forgetting its basic principles. It may not have the grandeur of Unforgiven or the spectacle of a Dirty Harry film, but it does have some of the most quietly effective filmmaking in cinema with two career-best performances at its core (no small claim given the success of both actors). It’s proof that simplicity can often be the greatest thing a film can do, and exemplifies how Eastwood has mastered the art of minimalistic filmmaking.

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.