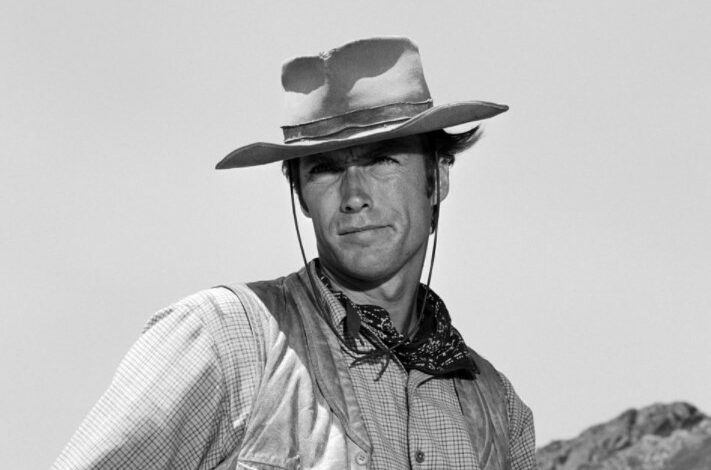

The lanky, long-faced Mr. Cord actually bears a closer resemblance to Tom Tyler, who played the Ringo Kid’s gun-slinging nemesis, Luke Plummer, in the John Ford film, than he does to the towering, barrel-chested Wayne. Under Douglas’s direction, Mr. Cord creates a less charismatic but more approachable Ringo.

In the original film, Ford introduces Wayne with a highly uncharacteristic visual flourish: the camera darts toward Wayne in a rapid dolly shot, as the actor, standing in front of what appears to be a projected background, twirls his rifle in a grand, theatrical gesture. The shot briefly goes out of focus as Ford’s cinematographer, Bert Glennon, struggles to keep up with the change in scale — an effect that may have been accidental, but which grants Wayne an almost supernatural aura, as his face emerges from the blur to fill the screen in a dominating close-up.

This is mythmaking, pure and simple. Douglas, by contrast, discovers Mr. Cord’s Ringo sitting by the side of the road, in a roomy, wide-screen composition that fully integrates the actor with natural environment. In the background, a rushing waterfall imparts some of its strength and wonder to the character, but Douglas soon moves to a higher angle that eliminates the waterfall from the image, and actually seems to diminish Ringo’s stature by looking down on him, hemmed in by a cluster of trees.

Sign up for the Watching newsletter, for Times subscribers only. Streaming TV and movie recommendations from critic Margaret Lyons and friends. Try the Watching newsletter for 4 weeks.

There’s no Homeric apotheosis here, just a frank appraisal of a man who lives within the limits of the natural world. The comparison illuminates the difference between two films and two filmmakers working from what is essentially the same script (although the rewrite, by Joseph Landon, expands some scenes and eliminates others, large passages of Dudley Nichols’s original dialogue are recycled).

While Ford was indisputably the greater artist, Douglas has put his finger on one of the weaknesses of “Stagecoach”: Ford’s determination to make a sort of meta-western, a film that deals in archetypes rather than individuals, and epic themes rather than genre conventions. With “Stagecoach,” Ford’s return to the genre after 13 years of more “prestigious” material, the western achieves self-consciousness, an awareness of itself as America’s official foundation myth.

Douglas almost literally brings the material back to earth, shifting the action from the black-and-white, lunar landscape of Monument Valley (“Stagecoach” was the first film that Ford shot among its eerie promontories) to the fecund greenery of a Colorado mountain range. Ford, in Andrew Sarris’s famous phrase, keeps his eye on the horizon line of history; Douglas, whose sensibility is at once more pessimistic and humanistic than Ford’s, concentrates on the immediate problems facing the characters in the foreground.

Image

Mr. Cord with Ann-Margret, his romantic partner in the film.Credit…Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment

The 1966 “Stagecoach” is an intriguing anticipation of the disaster-film cycle that would begin in earnest with “Airport” in 1970. An all-star cast (for 1966, at least — Ann-Margret, Red Buttons, Mike Connors, Bing Crosby, Robert Cummings, Van Heflin, Slim Pickens, Stefanie Powers) faces an apocalyptic threat (provided in “Stagecoach” by some uncharacterized Indians, the weakest element in both movies) while trapped within a restricted environment, much like the casts of “The Poseidon Adventure” and “The Towering Inferno.”

But what at first seems a threat becomes a sort of therapy, as some characters reveal their hidden weaknesses (Cummings’s smiling, sanctimonious banker has a satchel full of stolen cash), others discover their hidden strengths (Crosby’s alcoholic doctor sobers up long enough to deliver a baby), while the frayed social network pulls more tightly together.

The 1970s disaster films would add a theological dimension (remember the inverted Christmas tree in “The Poseidon Adventure”?) that remains quite foreign to Douglas’s pragmatic personality. There is nothing metaphorical or metaphysical about the violence in “Stagecoach,” which retains the shocking, graphic immediacy that Douglas pioneered in films like “Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye” (1950) and “Them!” (1954).

In Ford’s film, the great set piece is the Indian attack on the stagecoach as it crosses an open stretch of desert. Douglas, no doubt wary of trying to surpass one of the most famous sequences in film history, almost throws away the scene. He covers Ford’s epic vistas with a single helicopter shot and quickly moves the chase into a wooded area, where it ends, not with the magnificent sense of release and deliverance of Ford’s film, but in a squalid shootout.

Instead, Douglas concentrates on Ringo’s last-reel showdown with Luke Plummer, a scene played so perfunctorily by Ford that it seems like an anticlimax (though a brilliant one, I think). For Douglas, the darkened western town, with its deserted streets and little pools of light, becomes an urban jungle right out of one of his early films noirs, and Ringo’s confrontation with a vigorously characterized, actively sadistic Plummer (Keenan Wynn) is brutal and personal.

When John Wayne’s Ringo rides off with his newfound love (Claire Trevor, as the “saloon girl” with a heart of gold), Ford seems to imagine them as a new Adam and Eve, whose children will populate an American Eden of freedom and democracy. Alex Cord’s Ringo enjoys a more prosaic fate, but perhaps a less burdensome one: when he rides away with his saloon girl (a young and impossibly lush Ann-Margret), we see a couple of kids escaping an adult world that has become too corrupt and confining for them.

“Stagecoach” did not make Cord a star, but it didn’t destroy him: he moved into Euro-westerns and television (including a long run as a star of the CBS series “Airwolf”) and today raises horses and writes novels. That seems to me a happy ending, too. (Twilight Time, available exclusively through screenarchives.com, $19.95)

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

John Wayne | Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

John Wayne | Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images