The year 1969 was a true inflection point for the American western, a once-dominant genre that had become a casualty of the culture, particularly when Vietnam had rendered the moral clarity of white hats and black hats obsolete. A handful of westerns were released by major studios that year, including forgettable or regrettable star vehicles for Burt Reynolds (Sam Whiskey) and Clint Eastwood (Paint Your Wagon), who were trying to revitalize the genre with a touch of whimsy. But 50 years later, three very different films have endured: Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Wild Bunch and True Grit. Together, they represented the past, present and future of the western.

![MIDNIGHT COWBOY [US 1969] JON VOIGHT AND DUSTIN HOFFMAN A JEROME HELLMAN PRODUCTION](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/7eedde8f05a2ba5192f1d713fa069a78dd023441/0_170_3592_2156/master/3592.jpg?width=460&quality=85&auto=format&fit=max&s=9610addf4332242f3aeb7cd184e24ab2)

Midnight Cowboy at 50: why the X-rated best picture winner endures

In the present, there was Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, the year’s runaway box-office smash, grossing more than the counterculture duo of Midnight Cowboy and Easy Rider, the second- and third-place finishers, combined. George Roy Hill’s hip western-comedy, scripted by William Goldman and starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford, turned a story of outlaw bank robbers into a knowing and cheerfully sardonic entertainment that felt attuned to modern sensibilities. Sam Peckinpah’s Wild Bunch predicted a future of revisionist westerns, full of grizzled antiheroes, great spasms of stylized violence, and the messy inevitability of unhappy endings. A whiff of death from a genre in decline.

By contrast, True Grit looks like it could have been released 10, 20 or 30 years earlier, and with many of the same people working behind and in front of the camera. Its legendary producer, Hal B Wallis, was the driving force behind such Golden Age classics as Casablanca and The Adventures of Robin Hood, and his director, Henry Hathaway, cut his teeth as Cecil B DeMille’s assistant on 1923’s Ben Hur before spending decades making studio westerns, including a 1932 debut (Heritage of the Desert) that gave Randolph Scott his start and seven films with Gary Cooper. And then, of course, there’s John Wayne as Rooster Cogburn, stretching himself enough to win his only Oscar for best actor, but drawing heavily on his own pre-established iconography. It was, for him, a well-earned victory lap.

True Grit may be defiantly old-fashioned and stodgy when considered against the films of the day, but it’s also an example of how durable the genre actually was – and how it would be again in 2010, when the Coen brothers took their own crack at Charles Portis’s 1968 novel and produced the biggest hit of their careers. What would be more escapist than ducking into a movie theater in the summer of ’69 and stepping into a time machine where John Wayne is a big star, answering a call to adventure across a beautiful Technicolor expanse of mountains and prairies? The film has much more sophistication than the average throwback, but the search for justice across Indian Territory is uncomplicated and righteous, and the half-contentious/half-sentimental relationship between a plucky teenager and an irascible old coot grounds it in the tried-and-true. The defiant message here is: this can still work!

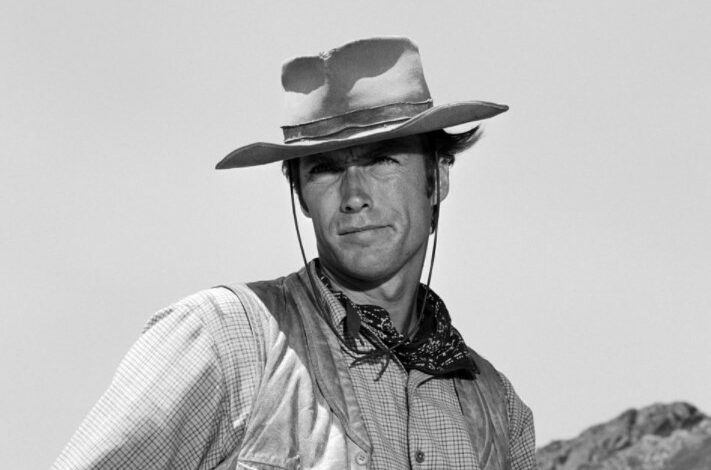

Photograph: Paramount/Kobal/Rex/Shutterstock

Photograph: Paramount/Kobal/Rex/Shutterstock

And boy does it ever. Kim Darby didn’t get much of a career boost for playing Mattie Ross, a fiercely determined and morally upstanding tomboy on the hunt for her father’s killer, but every bit of energy and urgency the film needs comes from her. When Mattie’s father is shot by Tom Chaney (Jeff Corey), a hired hand on their ranch near Fort Smith, Arkansas, she takes it upon herself to make sure he’s caught and dragged before the hanging judge. Whatever emotion she feels about the loss is set aside, limited to a brief crying jag in the privacy of a hotel bedroom, and she’s all business the rest of the time. When the Fort Smith sheriff doesn’t seem sufficiently motivated, she seeks out US marshal Cogburn (Wayne), a one-eyed whiskey guzzler who lives alone with a Chinese shopkeep and a cat he calls General Sterling Price.

The odd man out in their posse is a Texas ranger named La Boeuf (Glen Campbell), which Wayne and everyone else pronounce as “La Beef”, as part of his instinctual disrespect for Texans – and, really, anyone who fought for the Confederacy during the civil war. (La Boeuf makes a point of saying he fought for General Kirby Smith, rather than the south, which suggests a sense of shame that stands out in our current age of tiki-torch monument protests.) The chemistry between the three is terrific, despite Campbell’s limitations as an actor, because it’s constantly changing: Rooster and La Boeuf are sometimes aligned as mercenaries who see Chaney as a chance to take money from Mattie and from the family of a Texas state senator that the scoundrel also shot. Rooster comes to Mattie’s defense when Le Boeuf treats her like a wayward child and whips her with a switch, but the tables turn on that, too, when Rooster’s protective side holds her back.

Wayne called Marguerite Roberts’ script the best he’d ever read – she was on the Hollywood blacklist, which made them odd political bedfellows – and True Grit has nearly as much pop in the dialogue as the showier Butch Cassidy. Mattie gets to turn her father’s oversized pistol on Chaney, but language is her weapon of choice, delivered in such an intellectual fusillade that her adversaries tend to surrender quickly. (A running joke about the lawyer she intends to sic on them has a wonderful payoff.) The three leads exchange playful barbs and colorful stories, too, with Rooster ragging on La Boeuf’s marksmanship (“This is the famous horse killer from El Paso”) or spending the downtime before an ambush sharing the troubled events from his life that have gotten him to this place.

There’s a degree to which True Grit is a victory lap for Wayne, who gets one of his last – and certainly one of his best – opportunities to pay off a career in westerns. Yet Wayne genuinely lets down his guard in key moments and allows real pain and vulnerability to seep through, enough to complicate his tough-guy persona without demolishing it altogether. It may not have the gravitas of Clint Eastwood in Unforgiven, but it’s the same type of performance, the reckoning of a western gunslinger who’s seen and done terrible things, lost the people he loved, and seems intent on living out his remaining days alone. Without the redemptive power of Mattie’s kindness and decency, True Grit is about a man left to drink himself to death.

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

![MIDNIGHT COWBOY [US 1969] JON VOIGHT AND DUSTIN HOFFMAN A JEROME HELLMAN PRODUCTION](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/7eedde8f05a2ba5192f1d713fa069a78dd023441/0_170_3592_2156/master/3592.jpg?width=460&quality=85&auto=format&fit=max&s=9610addf4332242f3aeb7cd184e24ab2)

Photograph: Paramount/Kobal/Rex/Shutterstock

Photograph: Paramount/Kobal/Rex/Shutterstock

John Wayne | Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

John Wayne | Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images