Lorey SebastianIt doesn’t take rocket science to see why True Grit enjoyed the biggest opening weekend of any Coen brothers movie to date. The film may not have won the Coens their most rapturous reviews (though the critics were largely enthusiastic), and it’s hardly their best or most defining work. Yet it’s a remake of a famous and, indeed, iconic Hollywood movie — one that, while not quite a “classic,” remains a robust and beloved end-of-the-studio-system-era Western. OMG, I used the R-word! — I called True Grit a “remake.” The vulgarity, the lowbrow cluelessness on my part! From the outset, you see, the directorial and studio spin on this movie has been to insist that it’s a completely different animal from the deeply sentimental 1969 when-fresh-faced-teenybopper-met-grizzled-old-marshal fable of popular vengeance. The Coens, making their publicity rounds, have talked and talked about how they went back to Charles Portis’ original novel, which was published in 1968. But if, like me, you’ve never read the novel (and I would guesstimate that 97 percent of the people who saw True Grit over the weekend have not), then after all the remake? what remake?! spin, you might be startled to see how close the movie really does come to the 1969 version. At times, it borders on being a scene-for-scene, line-for-line gloss on it.

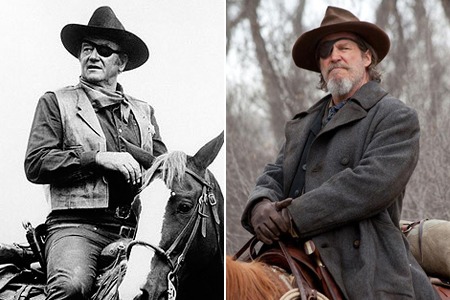

There are differences, of course. The Coen brothers’ version is more tasteful and intimate and art-directed, a kind of color-coordinated curio. Hailee Steinfeld’s Mattie Ross is notably younger than Kim Darby’s (which, at times, makes the new Mattie seem even more of an old movie concoction), and major sections of the picture are set at night (a technique that worked a lot better in No Country for Old Men). That said, the essential hook of the new True Grit is, and always was, the sheer curiosity factor of wanting to see Jeff Bridges, in his born-again middle-aged movie-star prime, take on the role of Rooster Cogburn, the part that won John Wayne his only Academy Award.

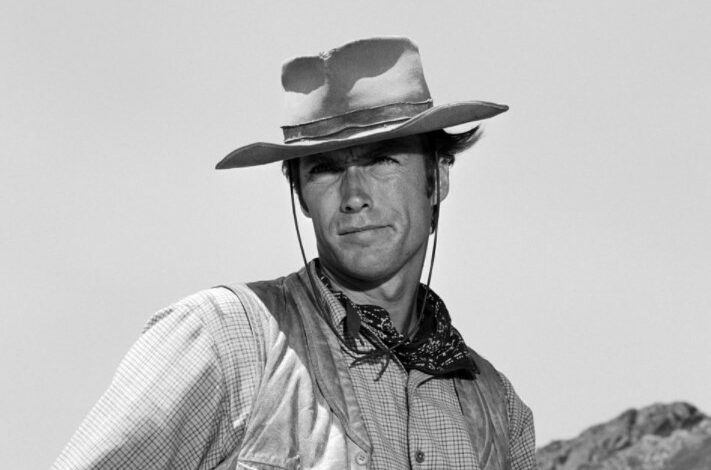

There’s a reason that a great many people still don’t hold Wayne’s cornball-crusty performance in very high esteem. By the late ’60s, movies were in the middle of a revolution, and they had a new audience, known (it now sounds so quaint) as the Film Generation. At the time, a lot of folks under a certain age felt that it was almost their duty to hate John Wayne. He’d become the living embodiment of the Old Values. He was a saber-rattling conservative who, only the year before, in 1968, had pushed his pro-Vietnam hawkishness to the nth degree in the jarringly jingoistic The Green Berets. He had every right to, of course. But what made The Green Berets, as a corrective to Hollywood liberalism, so infamous and despised is that it was such a didactically wooden combat movie. All that came through, really, was the propaganda. And this reinforced the notion that Wayne, though he remained the most larger-than-life of all Hollywood movie stars, was never, in the fullest sense, an actor. He had come to be seen as the macho cartoon version of himself: the arms-out swagger, the slow-motion molasses drawl, the toughness that never wavered.

True Grit, the movie that finally won Wayne his Oscar, was transparently one of those movies designed to win an old warhorse legend his Oscar. Here he was — or so the rap went — running through his rawhide-cowboy shtick, only this time with the added gimmick of an eye patch and an attitude. As if to make him seem even more outdated, True Grit was released within a week of The Wild Bunch, the apocalyptic New Hollywood Western in which director Sam Peckinpah, spattering blood and bullets and doom, exploded the mythology of six-gun heroism that John Wayne incarnated. If you love movie-star acting, however, do yourself a favor: Get a hold of the original True Grit and watch it. Because what you’ll see is that John Wayne’s performance is a marvel. He makes Rooster Cogburn a cantankerous old cuss, a kind of cowpoke precursor to Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry — the kind of law enforcer who never met a bad guy he didn’t like to shoot.

Wayne’s Rooster lives by a code, all right, but the movie suggests that he’s trapped by it as well. In one of the key scenes that’s more or less duplicated in the Coen brothers version (though to far less emotional effect), he talks about his past, including his wrecked marriage, and we see that he’s the sort of “noble” loner who’s really a broken-down, half-dead codger. Killing bad guys isn’t just his mission — it’s the major thing that’s keeping him alive. At the same time, he’s an irresistible rascal whose one-eyed squint becomes a wink of valor. Forty years later, Wayne’s performance has aged beautifully, because it’s easier to see now how much acting there really is in it. There is one moment, though, that almost by definition can’t match the power it had back in 1969: When Wayne’s Rooster, just before the famous, climactic, reins-in-his-mouth shoot-out, growls out the line “Fill your hands, you son-of-a-bitch!”…there’s simply no way to recapture how funny-edgy, and even shocking, it once was to hear John Wayne, apostle of American values, spit out an epithet like that. The glory of it, of course, is that the real son-of-a-bitch was Rooster.

And how does Jeff Bridges do? The consensus seems to be: pretty well. And I would agree. He’s winningly gruff, he looks fine and nasty in that grizzly beard, he’s got the body language of “Saddle-Sore Old Drunken Law Enforcer” down pat, and he wears that eye patch as if he’d never once taken it off in 15 years. To me, though, Bridges’ performance lacks the raw magic of Wayne’s, because it rarely, if ever, surprises you. After a while, that croak of his gets a little bit samey. This has something to do with the fact that Bridges, as great an actor as he is, has something of an inner Teddy Bear quality. He’s cuddly and humane, even when playing a crank like Rooster; we warm up to the character almost too quickly. More than that, though, I wish that the Coen brothers, in creating their 2010 version of Rooster Cogburn, had departed from the book and made him a touch wilder — given him, say, not just a missing eye but a missing limb, something (anything) to suggest that he’s not just Mattie’s crusty savior but one hellacious, damaged dude. If they’d done that, their True Grit would have been not only grittier but something that the first movie is and this movie may not be: memorable.

So where do you stand on the two Rooster Cogburns? Which one has more true grit? Which actor, in the end, gives a better performance — the Duke or the Dude? Or am I wrong to even suggest that there should be a contest between them?

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

John Wayne | Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

John Wayne | Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images