Joel and Ethan Coen’s True Grit is their second remake of a classic film. The first, The Ladykillers (a noisy reimagining of the understated 1955 Ealing Studios comedy), was by almost any reasonable account the brothers’ worst film. True Grit is also, arguably, the Coens’ second Western, following 2007’s No Country for Old Men—by general consensus, their finest work. It is perhaps fitting, then, that True Grit lies squarely between these two poles of their career: a fine but middling production by the duo’s elevated standards.

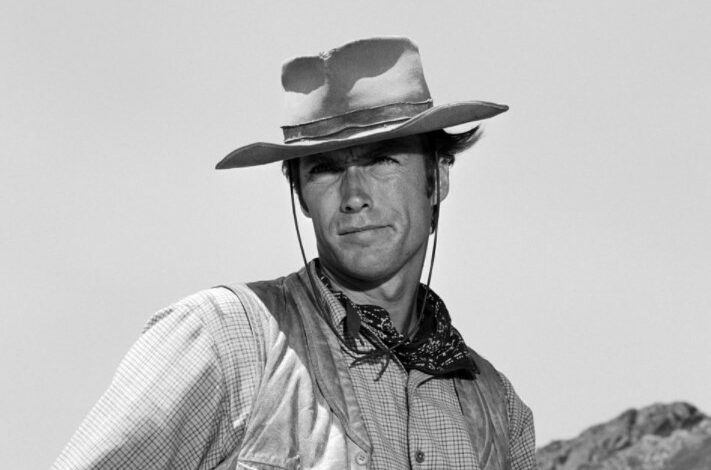

The 1969 version of True Grit, directed by Henry Hathaway, won John Wayne his only Oscar in the role of Arkansas marshal Rooster Cogburn; the Coens’ remake would seem intended to do the same for Jeff Bridges, if not for the fact that it comes a year too late. Indeed, there are notable similarities between Cogburn and Crazy Heart‘s Bad Blake, the role that earned Bridges his Academy seal-of-approval last year: both are ornery, likable drunks, who were exceptionally good at their chosen professions until they decided to set up residence in a bottle. Yes, Cogburn is a killer and Blake a singer, but that is merely the difference between Western and Country & Western.

As in the earlier film, and the Charles Portis novel on which it is based, Cogburn is hired by a headstrong 14-year-old girl, Mattie Ross (Hailee Steinfeld), to track down and punish Tom Chaney (Josh Brolin), the lowlife who murdered her father and fled into Indian territory. Mattie also demands, improbably but immovably, that she accompany Cogburn on the mission. They are intermittently accompanied in their vengeful endeavor by an epicene Texas Ranger named La Boeuf (Matt Damon), who wishes to see Chaney hanged for an unrelated infraction.

They encounter the typical obstacles along the way: snappish snakes, unforgiving elements, and a passel of auxiliary desperadoes (including Barry Pepper, whose small but excellent performance—in a role played by Robert Duvall in the original—is bested only by that of the makeup technician responsible for his terrifyingly snaggled dentition). But in classic Western tradition, the tale is largely a journey from point A to point B, from crime to punishment. There are heavy echoes of Unforgiven, of Lonesome Dove, and of the countless Westerns they were themselves echoing.

After the triumph of No Country for Old Men, the Coens would seem a perfect match for such material: for the stark, unforgiving expanses of the Old West and the laconic antiheroes who prowled it. The problem is that while the former is in gorgeous evidence, the latter are nowhere to be found. Cogburn, Mattie, and La Boeuf are all inveterate talkers, and hardly a minute goes by without the airing of some boast, dispute, or complaint. The precocious Mattie is a particular problem, her hyperactive patter awkwardly recalling that of Nicolas Cage’s H.I. McDunnough in Raising Arizona and George Clooney’s Ulysses Everett McGill in O Brother, Where Art Thou. (In the 1969 film, Mattie was played by 21-year-old Kim Darby; Steinfeld, by contrast, is actually 14, rendering her a more plausible child but, paradoxically, a less plausible protagonist.) I held out hope for the appearance of Josh Brolin, who elevated taciturnity to an art in No Country, but despite his above-the-title billing, his role in the film is largely perfunctory.

Ultimately, it’s hard to shake the sense that the Coens opted to remake the wrong Western. True Grit is a sentimental tale, at least by the standards of the genre, and the Coens are not—to put it mildly—sentimentalists. They restore a few of the more somber elements of the Portis novel, but this is still the story of a plucky girl and her grizzled companion and, as such, perhaps best suited to the ingenuous tone of the 1969 version.

That’s not to say the Coens’ film is without its strengths: a good, if slightly familiar performance by Bridges; a nice, customarily modest turn by Damon, who may be the most versatile star working today; and, of course, the brothers’ usual technical prowess.

But the real reason to see the film is the work of the Coens’ regular collaborators, cinematographer Roger Deakins and composer Carter Burwell, who supply the visual and auditory landscapes that are True Grit‘s most notable achievement. (Burwell’s evocative score, which consists largely of delicate variations on the hymn “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms”—and recalls his magnificent appropriation of “Limerick’s Lamentation” in Miller’s Crossing—is alone worth the price of admission.)

Deakins has shot every Coen brothers movie since 1991’s Barton Fink (along with such beautiful films as The Shawshank Redemption, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, and Revolutionary Road); Burwell’s fruitful collaborations with the Coens date back further still, all the way to their 1984 debut Blood Simple. Neither man, I am dismayed to report, has ever won an Academy Award. It seems unlikely that this oversight will be corrected by as modest a vehicle as True Grit. But one can dream.

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment2 years ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

John Wayne | Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

John Wayne | Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images