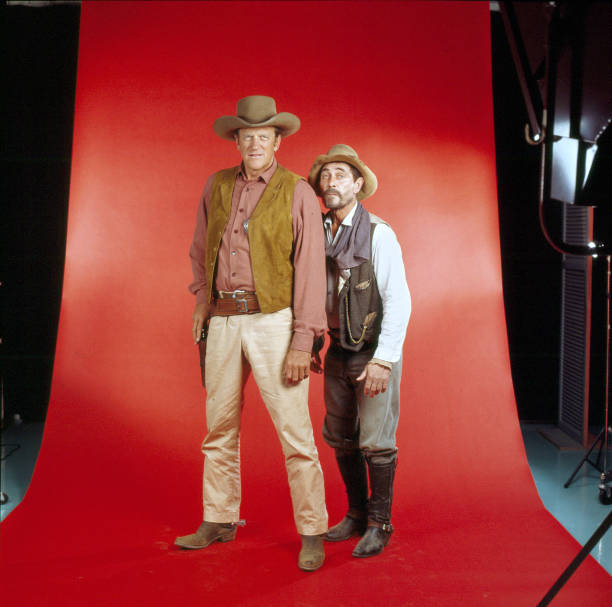

James Arness, who burnished the legend of America’s epic West as Marshal Matt Dillon, the laconic peacemaker of Dodge City on “Gunsmoke,”

. Mr. Arness was terribly shy and had almost no training as an actor. A wartime leg wound made it painful for him to mount a horse. But he became the best-known tin star of his era, portraying the towering, weathered marshal for 20 years, from 1955 to 1975. He also made some 50 films and television movies, mostly westerns, in a career that stretched across five decades.

To a generation of television viewers, Mr. Arness and “Gunsmoke” embodied a new, more adult vision of the mythic Old West: a quiet, vulnerable lawman facing not stereotyped villains and clichéd situations but a chaotic frontier freighted with moral judgments and occasional failure. He might be too late to stop a killing. He could save a girl from kidnappers, but not from her father’s brutality.

Audiences had long been accustomed to western heroes who never were, having been sanitized by the trail songs of Gene Autry and Roy Rogers and the righteous gunplay of the Lone Ranger and Hopalong Cassidy . But Marshal Dillon never got the girl, did not love his horse, wore only one gun and fired it reluctantly, usually drawing last but shooting straightest in dusty street duels. Over the years, the marshal was shot 30 times.

Mr. Arness, a 6-foot-7 giant whose stoic personality was remarkably like his character’s, was ideal for the part. He had been reared in a family of Norwegian descent in Minnesota and became an outdoorsman who loved fishing and hunting. He came home from World War II a wounded, decorated and aimless veteran. He worked menial jobs, tried radio and was collecting veterans’ benefits when he drifted to Hollywood.

He developed slowly, appearing in 30 movies before his mentor, John Wayne, rejected the Dillon role and recommended him instead. “Gunsmoke,” which began in 1952 as a radio show with William Conrad, landed on the CBS television network as a half-hour black-and-white drama set in a raw Kansas town in 1873.

In the premiere, which established the tone for the series, Marshal Dillon faces a gunslinger who had killed an unarmed man. The outlaw insists on a showdown, and the marshal, always a moral touchstone, must accommodate him.

“He’s a gunman, Doc,” Dillon says to Doc Adams. “He has got to be eliminated.”

The supporting cast was a snug family, stock but multilayered characters who spent much time talking: the beer-drinking philosopher, Doc (Milburn Stone); the careworn Long Branch saloonkeeper, Miss Kitty (Amanda Blake), her love unrequited; and the lame sidekick, Chester Goode (Dennis Weaver). Characters and actors came and went in tales that often focused on travelers passing through on their way west.

Gunsmoke” was not an instant success. But from 1957 to 1961, when it became a one-hour series, it was the top-rated show on television, seen every week by 40 million Americans and millions more in Britain, where it was called “Gun Law.” It bred dozens of copycats, including “Have Gun, Will Travel,” “Wagon Train,” “Rawhide,” “The Rifleman” and “Bonanza.”

The ratings declined until 1967, when color and a new time slot sent “Gunsmoke” back into the Top 10 until the 1973-74 season. The show was still in the Top 30 when it was canceled in 1975. In its 20-year run, there had been 635 episodes. Mr. Arness had been in the saddle for all of them, and would ride again through decades of reruns and sequels.

He was born James King Aurness in Minneapolis on May 26, 1923, one of two sons of Rolf Aurness, who sold medical supplies, and the former Ruth Duesler. (His parents divorced in the 1940s.)

Mr. Arness’s younger brother was the actor Peter Graves, who starred for years on television in “Mission: Impossible” and appeared in scores of movies, including “Airplane!” (1980) . He died in March 2010.

James attended public schools and graduated from West High School in Minneapolis in 1942.

In his first year at Beloit College in Wisconsin, Mr. Arness was drafted into the wartime Army as an infantryman. During the invasion of Anzio, Italy, in 1944, his right leg was shattered by machine-gun fire. Hospitalized for nearly a year, he underwent a series of operations but for many years suffered pain, especially when mounting a horse, and walked with a slight limp. He won the Bronze Star and the Purple Heart.

After the war he returned to Minnesota, took odd jobs and was a radio announcer before moving to Los Angeles in 1946. He began acting at an amateur theater and met the producer Dore Schary, who put him in a few movies in 1947. Unsure of his future, he drifted around Mexico, but returned to Hollywood determined to be an actor called James Arness.

In 1948 he married Virginia Chapman and adopted her son by a previous marriage, Craig. The couple had two children, Jenny and Rolf, and were divorced in 1963. In 1978 he married Janet Surtees; they lived in the Brentwood section of Los Angeles. She and Rolf Arness survive him, along with a stepson, Jim Surtees. Survivors also include six grandchildren and a great-grandchild. Jenny Arness died in 1975, and Craig in 2004.

Critics praised Mr. Arness’s performance as an unjustly accused man in “The People Against O’Hara” (1951), and he was memorable if unrecognizable in the title role of the science-fiction thriller “The Thing From Another World,” better known as just “The Thing” (1951). In the next few years he was in dozens of films, including “Big Jim McLain” (1952) and “Hondo” (1953), which both starred John Wayne.

Wayne was one of Hollywood’s biggest stars then, and a television role did not seem the right move for him. But Mr. Arness, his protégé, turned out to be a masterly casting choice. Its 20-year tenure made “Gunsmoke” the longest-running scripted prime-time show in American television history, a record that stood until it was broken by “The Simpsons” in 2009. (“Law & Order” reached the 20-year mark in 2010, but was canceled before it could overtake “Gunsmoke.” No other show currently on the air comes close.) Besides reruns, it spun off books, board games, a trove of merchandise and endless nostalgia.

Mr. Arness was nominated for three Emmy Awards in the “Gunsmoke” years and later made dozens of television movies, including “The Alamo” (1987) and “Red River” (1988). He also starred in the mini-series “How the West Was Won” (1977) and the short-lived crime series “McCain’s Law” (1981). From 1987 to 1993 he also made five “Gunsmoke” television-movie sequels. “James Arness: An Autobiography,” written with James E. Wise Jr., was published in 2001.

PROC. BY MOVIES

Entertainment7 months ago

Entertainment7 months ago

Entertainment7 months ago

Entertainment7 months ago

Entertainment8 months ago

Entertainment8 months ago

Entertainment9 months ago

Entertainment9 months ago

Entertainment7 months ago

Entertainment7 months ago

Entertainment8 months ago

Entertainment8 months ago

Entertainment7 months ago

Entertainment7 months ago

Entertainment7 months ago

Entertainment7 months ago