In The Big Trail, we got the first glimpse of a future icon. The Shootist found him teeming with wisdom and experience.

The Big Trail (1930)

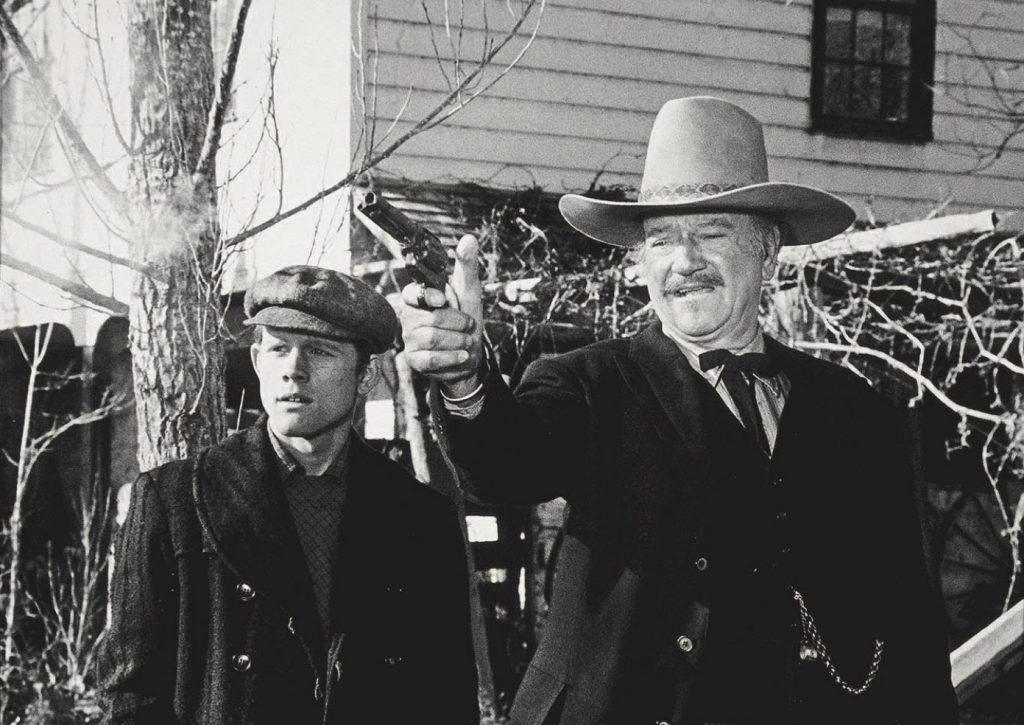

John Wayne, Tyrone Power, and Ian Keith in 1930’s The Big Trail, directed by Raoul Walsh.

John Wayne, Tyrone Power, and Ian Keith in 1930’s The Big Trail, directed by Raoul Walsh.

“Hiya, Zeke!” That’s his first line. And with its delivery one can see that he’s got … it. It is the word we sometimes use when attempting to describe that indefinable quality of great leading men. For this young man, it is a simple charm that emerges from the lack of any need to charm. It is the ability to truly engage with the performers around him rather than to indicate a vague idea of engagement. And through that young man’s clear-eyed understanding of a job done honestly, we find ourselves witnessing the birth of an American identity that bleeds across our screen like celluloid caught aflame.

It was 1930 when a 22-year-old Marion Mitchell Morrison was stolen off the properties crew of a John Ford film and screen tested for a Raoul Walsh project. Subsequently, he would be renamed “John Wayne” by the Fox Film Corporation’s publicity arm and handed $75 a week to take on the leading role in one of the riskier investments in Hollywood history. It is often reported that The Big Trail represents one of Hollywood’s earliest attempts to convert the movie experience into a widescreen format, ultimately flopping because the financial constraints of the Great Depression had left movie houses unable to convert to the newer technology. While the first part is true, the actual record is a bit more complex.

There are, in fact, two English language versions of this wagon-train epic (a plethora of foreign language versions were also shot in subsequent takes with different actors). Studio founder William Fox was known to occasionally take a risk, but he was not a blind gambler. Likely fearing the economic unrest of the time, Fox had Walsh shoot his film both in the traditional 35 mm format and in the newer 70 mm. Most scenes were filmed by two crews simultaneously, while others had to be repeated with more mise en scène for the expansive 70 mm “grandeur” frame. With almost 200 wagons, hundreds of oxen, cattle, horses, and extras, The Big Trail was early cinéma vérité in its depiction of a westward trek into untamed wilderness, made by a dogged crew slogging across locations that spanned seven states.

While Fox successfully hedged his bets (only two theaters in the nation were capable of screening the widescreen version when it was finally released), he found himself trying to market a film for which the predominant inspiration had been a new technology with a broad vista, a theatrical promise that was not possible to fulfill. The movie bombed spectacularly.

As was so often the case in Tinseltown, the sins of the father were visited upon the son, and Wayne found himself banished to the lesser sets of “B” westerns for a protracted sentence.

It would not be until 1939, when his old mentor and friend John Ford had generated enough power within his own productions, that Wayne would be given another big shot, this time as the iconic Ringo Kid in Stagecoach. This second entrance is brilliantly portrayed in the foreward of Scott Eyman’s carefully researched John Wayne: The Life and Legend (Simon & Schuster, 2014).

But The Big Trail remains a revelation, clairvoyant in its discovery of the genre’s greatest leading man and in its vision of what the film event would eventually become. Just take it from me: Make sure you watch the 70 mm version. There really is no comparison.

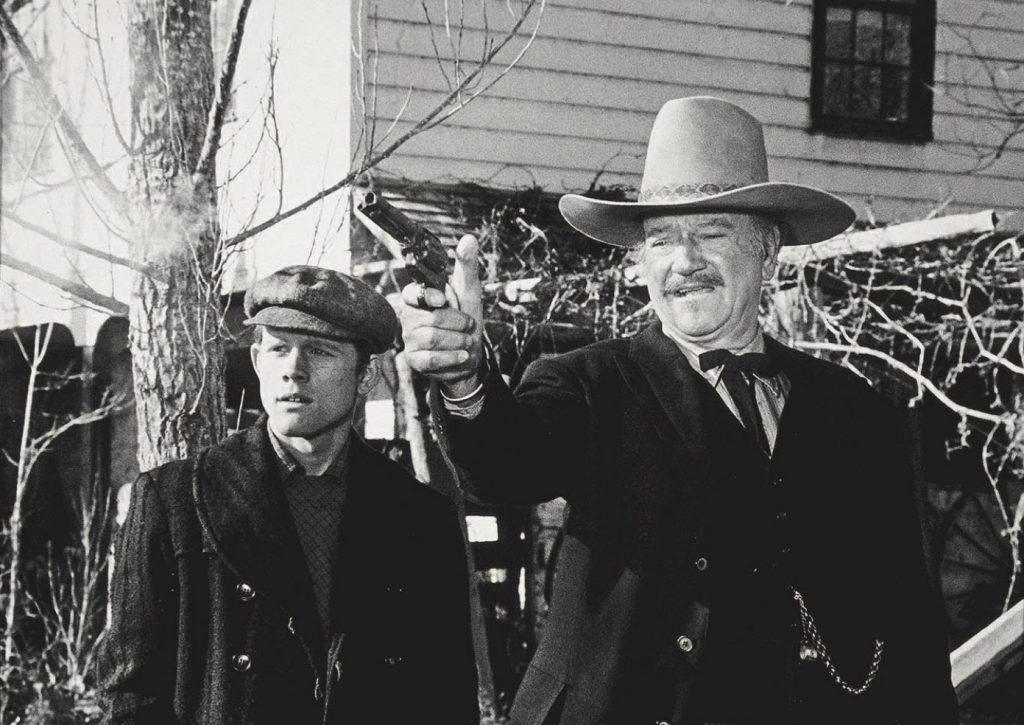

Ron Howard and John Wayne in 1976’s The Shootist, Wayne’s final western.

Ron Howard and John Wayne in 1976’s The Shootist, Wayne’s final western.

The Shootist (1976)

It’s a bit like that jolt you get when confronted with a photograph of your father in his younger years. Now take that dog-eared sepia of a young man squinting into the sunlight with his whole life ahead of him and place it next to the color Polaroid taken at his retirement party, that of a thicker man whose smile, while maybe not as broad, is supported by the assuredness of a life well spent. This is something akin to the experience of watching John Wayne’s first and last westerns back-to-back.

Of course, The Shootist is not often regarded as one of Wayne’s best. A multitude of factors play into this unfortunate exeunt for America’s leading man, the chief of them being the war of backstage egos that might have shamed even the greatest production of Julius Caesar, the principal senators here being Wayne and director Doug Siegel. Apparently, Siegel had never learned that the last person you want to tangle with on a set is an actor with power.

The script itself is a rather flat adaptation of the novel by Glendon Swarthout, an entirely passable but ultimately uninspiring western that was soured from too many fingers in the soup. Apparently, the screenwriters had never learned that the last person you want to collaborate with on a story is an actor with power.

But, according to Eyman, things were likely exacerbated by Wayne’s health, which was not at its best. It has been reported and rumored that Wayne’s portrayal of J.B. Books, a legendary gunslinger dying of cancer, was strangely poetic given that Wayne himself was battling cancer at the time. Others treat this claim as apocryphal, as Wayne had battled lung cancer a decade prior and lived. Again, the truth is always more complex.

While it is true that Wayne had a cancerous lung successfully removed in 1965, more than a decade later he would develop another malignancy, this one in his stomach, which would eventually take his life. By the time he was cast in The Shootist, the first cancer had gone into remission, but the parallels to a dying legend would not have been lost on any man who’d stared down the reaper and could still see him out there waiting in the plains.

Perhaps it was the knowledge of just such an inevitability that led to the Duke’s final performance being a perfect study of calm acceptance. A lesser actor, or a less experienced man, might have botched the role by layering it with angst and desperation. Instead, we are gifted with an almost whimsical acceptance of hard truths and a sweet farewell to the world he now realizes he never knew: a world in which humanity springs eternal like a tree splitting limestone.

Marion Mitchell Morrison, also known to the world as John Wayne, was laid to rest on June 15, 1979, at sunrise. Above him was set a tombstone that would remain unmarked for 20 years. When it was finally given an epitaph, it would be in Duke’s own words:

Tomorrow is the most important thing in life. Comes to us at midnight very clean. It’s perfect when it arrives and puts itself in our hands. It hopes we’ve learned something from yesterday.

Philosophical yet optimistic, it is a decent epitaph, though its purpose remains vague. It is perhaps the kind of phrase one might use as a kind of forked twig when trying to divine the extremely complex life and personality that was John Wayne. But this choice of epitaph is also ironic (and, to me, a bit sad) in that it was done in direct contradiction to a clearly stated wish that his future epitaph be nothing more than the following Mexican phrase: “Feo, Fuerte y Formal.” Translated it would have read:

John Wayne: Ugly, Strong and Dignified

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

John Wayne, Tyrone Power, and Ian Keith in 1930’s The Big Trail, directed by Raoul Walsh.

John Wayne, Tyrone Power, and Ian Keith in 1930’s The Big Trail, directed by Raoul Walsh.

Ron Howard and John Wayne in 1976’s The Shootist, Wayne’s final western.

Ron Howard and John Wayne in 1976’s The Shootist, Wayne’s final western.

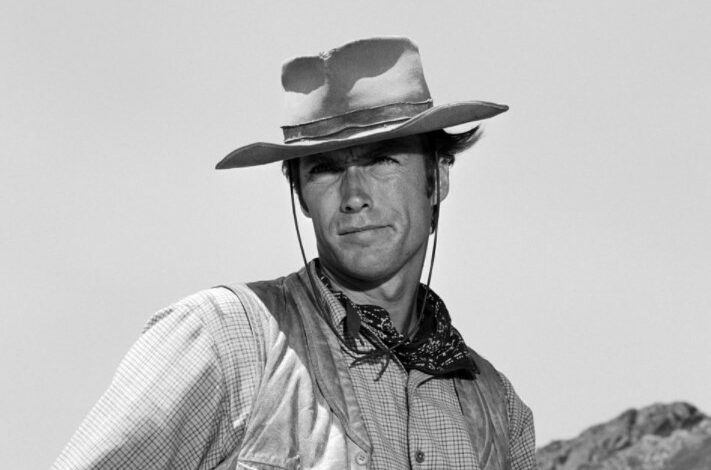

John Wayne | Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

John Wayne | Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images