I’m Spartacus!” – “I’m Spartacus!” – “I’M SPARTACUS!” Every film buff knows that moment, every panel-show comedian riffs on it. A mob of defeated slave rebels in the pre-Christian Roman empire is told their wretched lives will be spared, but only if their ringleader, Spartacus (Kirk Douglas), comes out and gives himself up to be executed. Just as he is about to sacrifice himself, one slave, Antoninus (Tony Curtis) jumps up and claims to be Spartacus, then another, and another, then all of them, a magnificent display of solidarity, while the man himself allows a tear to fall in closeup.

This variant on the Christian myth – in the face of crucifixion, Spartacus’s disciples do not deny him – is a pointed political fiction. In real life, Spartacus was killed on the battlefield. The screenplay was written by Dalton Trumbo, the blacklisted author who had to work under aliases and found no solidarity in Hollywood. Yet Douglas himself, as the film’s producer, stood up for Trumbo. He put Trumbo’s real name in the credits, and ended the McCarthy-ite hysteria.

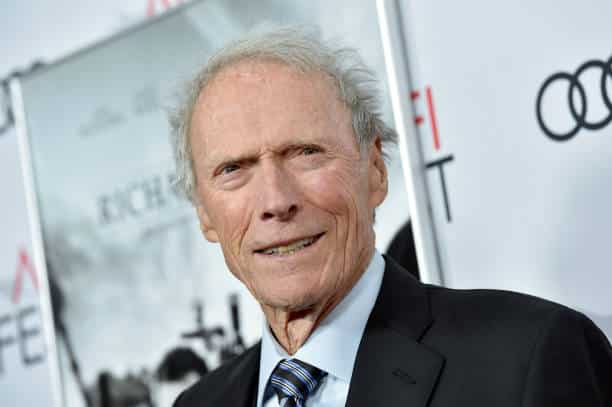

Kirk Douglas in SpartacusHe’s Spartacus: Douglas in his most famous role.The main reason the scene is so potent is its extraordinary irony. Who on earth could claim to be Spartacus when Spartacus looked like that? Douglas is a one-man Hollywood Rushmore, almost hyperreal in his masculinity. He is the movie-world’s Colossus of Rhodes, a figure of pure-granite maleness yet with something feline, and a sinuous, gravelly voice. Douglas is a heart-on-sleeve actor, mercurial and excitable; he has played tough guys and vulnerable guys, heroes and villains. And, as a pioneering producer, he brought two Stanley Kubrick films to the screen: Spartacus (he hired Kubrick to replace Anthony Mann) and his first world war classic Paths of Glory in which he was superb, playing a principled French army officer.

One hundred years ago today, Douglas was born Issur Danielovitch, the son of a Moscow-born Russian Jewish ragman, in upstate New York. An uncle had been killed in the pogroms at home. In his 1988 memoir, The Ragman’s Son, Douglas describes the casual antisemitism he faced almost throughout his career. Rebranding yourself with a Waspy stage-name was what actors – and immigrants in general – had to do in America to survive and thrive.

After a start on the Broadway stage, he made his screen reputation playing the driven fighter Midge Kelly in the exhilarating boxing movie Champion (1949), which earned him the first of his three Oscar nominations. Champion has stunning images and a notable slo-mo scene: it is much admired by Martin Scorsese and transparently an influence on Raging Bull. In Detective Story (1951), directed by William Wyler, Douglas gives a grandstanding star turn in a melodrama set in a police station, playing the vindictive, violent McLeod, an officer with an awful secret. It was a movie that laid down the template for all cop TV shows, including The Streets of San Francisco, which was to star Douglas’s son Michael.

But it was in Ace in the Hole (1951), directed by Billy Wilder, that Douglas gives his first classic performance: the sinister newspaper reporter Chuck Tatum, who prolongs the ordeal of a man trapped in a cave to create a better story. He is an electrifying villain in that film, a Phineas T Barnum of media untruth. At one stage he slaps the wife of the trapped man (whom he is also seducing) because she wasn’t sufficiently demure and sad-looking for his purposes, like an imperious film director looking for a better performance. He is also brilliant in Vincente Minnelli’s The Bad and the Beautiful (1952) as Jonathan Shields, the diabolically persuasive movie producer who betrays everyone.

Arguably, it is in Paths of Glory (1958) that Douglas finds his finest hour as the tough, principled Colonel Dax, who stands up to the callous and incompetent senior officers of the high command. Douglas’s handsome, unsmiling face is set like a bayonet of contempt.

Douglas himself prizes his sensitive and Oscar-nominated performance as Vincent van Gogh in another Vincente Minnelli film, Lust for Life, from 1956. Some may smile a little at this earnest and high-minded movie now, but it is very watchable, with a heartfelt belief that Van Gogh’s art can be understood by everyone. There is a bold, passionate performance from Douglas, who simply blazes with agony. Not everyone liked it. John Wayne famously stormed up to Douglas after a screening to rage: “Christ, Kirk, how can you play a part like that? There’s so goddamn few of us left. We got to play tough, strong characters. Not those weak queers!”

Douglas has endured a scene of almost Freudian trauma in his career. Having bought the rights to Ken Kesey’s novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest in the 1960s, he himself played the lead for its Broadway adaptation: McMurphy, the subversive wild-man imprisoned in a psychiatric hospital.

PROC. BY MOVIES

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago

Entertainment1 year ago