Entertainment

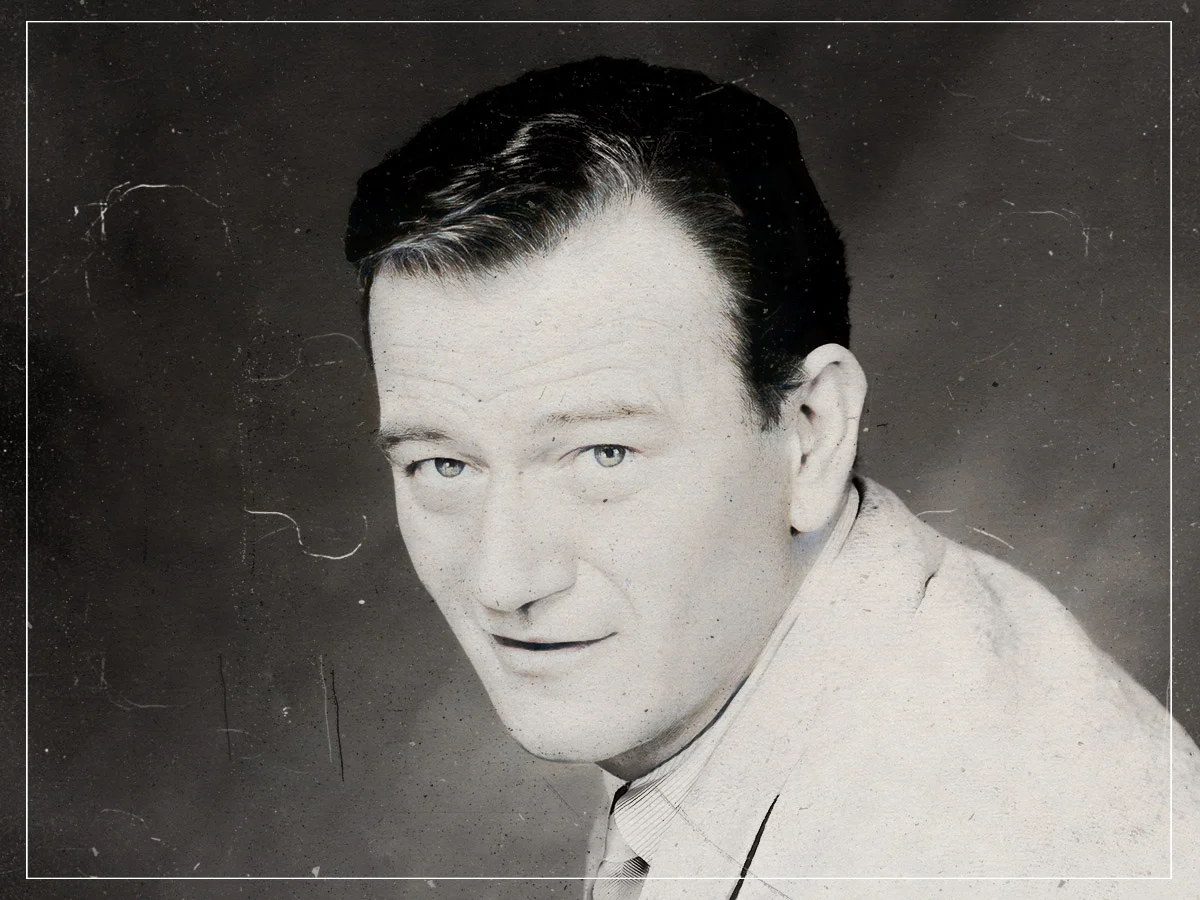

They say I’m an action actor, but I’m really a reaction actor…JOHN WAYNE – My Blog

The first time I met John Wayne was in 1965 in Old Tucson, Ariz., where he was shooting Howard Hawks’s “El Dorado.” They were doing a night scene so the lighting took a long time and, happily, gave me a solid two hours to sit on the set, not in his trailer, and to speak with the Duke about nothing except pictures. I hadn’t directed a movie yet, but I had been approved as a journalist by John Ford and endorsed by Hawks — the two most important directors in Wayne’s career — so he quickly became outgoing and pretty candid. When he was finally called away, he said to me, enthusiastically: “Geez, it was great talkin’ about . . . pictures! Nobody ever talks to me about anything but politics and cancer!”

Of course, he wasn’t kidding: By the mid-’60s, after 25 years of stardom and superstardom, most people would mainly talk about John Wayne’s conservative politics, either pro or con, or about his having survived lung cancer, with the loss of part of a lung. Hardly anyone spoke of his acting, except to take it for granted or to minimize it by saying he “always plays himself.” In his authoritative and enormously engaging new biography, “John Wayne: The Life and Legend,” Scott Eyman writes in great detail on all three subjects: the politics that led Wayne to be actively involved in the Hollywood Red Scare that blacklisted hundreds in the industry; the cancer that ultimately killed him in 1979 at age 72; and the surprising amount of care and work that went into creating the persona known to the world as John Wayne.

The portrait Eyman paints very much resembles the Wayne I knew for nearly 15 years: extremely likable, guileless, exuberant, even strangely innocent. Hawks, who cast him in “Red River” (1948), the major role for the second half of Duke’s career, once said to me that he felt everything that had happened to Wayne had gone a little “over his head.” Indeed, part of the charm of the man who was born Marion Robert Morrison in Winterset, Iowa, in 1907, was his lack of pretension or self-importance. Among the most interesting things I learned from this book are how well Wayne expressed himself in prose, how cogently he formulated his thoughts and what a good student he was. He had wanted, at one point, to be a lawyer, and the few writings Eyman quotes are quite impressive, especially because Ford liked to give the idea that his main star (whom he picked on mercilessly during shoots) was somewhat of an unlettered boob. One time, when I told Ford I was going to give Duke a book for a birthday present, Ford growled, “He’s got a book!”

Eyman begins his biography with an exciting prologue, describing the making of Wayne’s famous introductory shot in Ford’s first sound western, “Stagecoach” (1939), the picture that catapulted the actor overnight from grade-Z movies to the A-list of stars. It was a very unusual shot for Ford. It started with a full figure of Wayne, saddle over his shoulder, a rifle in his hand. The camera then rushes into a close-up, and Wayne twirls and cocks the rifle in one flamboyant gesture.

This is the movie in which John Ford — rejecting the producer’s choice, Gary Cooper, then a major box office attraction — decided to make Wayne a big star; when you see the picture, it seems quite a conscious decision, so much of it being shown from Wayne’s perspective. Although Duke had a minimal amount of dialogue, Ford made a point of always cutting to him for his reaction to whatever was being said or done. Silent reactions. A key foundation of the art of visual storytelling. Both Wayne and Ford grew up during the so-called silent era (so-called because it was never silent; there was always at least a piano or organ accompaniment, and often a full orchestra, with sound effects workers behind the screen). And in that period, silent close-ups were it. I’ve often heard it said that Ford made Wayne a star by giving him very few lines, but that isn’t the point: In pictures, a close-up reaction is worth a million words. Wayne used to sum it up: “They say I’m an action actor, but I’m really a reaction actor.”

The book that follows the arresting prologue takes you through Wayne’s life, his death and his legend in a detailed, remarkably knowledgeable yet extremely readable way. There’s an underlying tension in the writing that propels you forward. What’s more, having already published a fine biography of Ford, most aptly titled “Print the Legend,” Eyman had a head start on this book, a very important head start.

movies first as a goose-herder for Ford’s “Mother Machree” (1928), later as an all-around laborer, prop man, extra and bit player, mostly in Ford pictures. Ford obviously had his eye on Duke, but didn’t give him anything substantial.

Then in 1930, with the beginning of sound, the veteran director Raoul Walsh noticed Duke on the Fox lot, liked the way he moved and decided to cast him as the lead in an expensive, sweeping western epic, “The Big Trail,” one of the first films (and possibly the last for quite a while) photographed in wide screen. For his new job, Walsh decided the young man needed a better acting name than Marion Morrison, or even Duke Morrison; something more familiar, yet strong and decisive: And so John Wayne was born. The picture, which is actually quite likable (as is Duke in it), was a huge flop. And now Wayne, who had originally never thought of being an actor, was relegated to small parts in a few A-pictures, or leads in poverty-row westerns (very many of those).

Ford, who had been fatherly and very friendly — had indeed spoken well of Duke to Walsh — suddenly refused to speak to him or even acknowledge his existence; this went on for several years until finally, just as suddenly, he was back in the Ford family. This mysterious treatment, Wayne told me, was something he never understood. I venture to guess it was Ford’s way of punishing Duke for starring in a Walsh film, and letting Walsh be the one to change his name. James Cagney once said to me: “There’s one word that sums up Jack Ford — malice.”

You may like

Entertainment

The Christmas Western That’s Also One of John Wayne’s Best – My Blog

THE BIG PICTURE

3 Godfathers is a touching story of redemption, highlighting the capacity for even troubled characters to change. The film uses deliberately slow pacing to emphasize character development and showcase stunning natural environments. Christmas is an important part of 3 Godfathers, but the film’s positive message about humanity and forgiveness resonates beyond religious beliefs.

Few partnerships in cinematic history are quite as successful as John Wayne and writer/director John Ford. Ever since their first collaboration on the breakthrough 1939 adventure film Stagecoach, Wayne and Ford have told innovative stories about the American experience that revolutionized the Western genre. While Wayne starred in many Western classics, his work with Ford often embraced the darker side of the genre; 1956’s The Searchers featured one of cinema’s definitive anti-heroes, and 1962’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance examined the rise of political tension at the tail end of the Western era. Despite the gravity of many of their best collaborations, Wayne and Ford were also able to take a lighter approach to the genre. This is best evidenced by their delightful 1948 western 3 Godfathers, a Christmas-themed adventure movie that drew from Biblical passages. While on the surface it looked like a typical crowd pleaser, 3 Godfathers used its Christmas themes to tell a positive story of redemption.

3 GodfathersThree outlaws on the run risk their freedom and their lives to return a newborn to civilization.

Release DateJanuary 13, 1949DirectorJohn FordCastJohn Wayne , Pedro Armendáriz , Ward Bond , Mae MarshRuntime106 minutesGenresDrama , Western

‘3 Godfathers’ Is a Touching Story of Redemption3 Godfathers follows the cattle raiders Bob Hightower (Wayne), Pete (Pedro Armendáriz), and William “The Abilene Kid” Kearney (Harry Carrey Jr.), who rob a bank in the wholesome town of Welcome, Arizona. Ford intentionally starts the film like a typical Western and uses the opening sequence to examine the characters’ morality. Welcome is virtually undisturbed by violence, and is decorated with eloquent festive decorations. While the heist sequence itself doesn’t cause any significant damage and leaves no casualties, it’s enough to disrupt the fragile peace. Depicting Bob, Pete, and William as troublemakers that damaged a community gives them the capacity for redemption. Although many of Wayne’s leading roles were as nearly flawless heroes, 3 Godfathers forced him to play a character of a more checkered morality.

While the heist sequence is an exciting way to start the film, the inciting incident comes shortly thereafter when the three bandits become trapped in a brutal sandstorm and discover a covered wagon that has been damaged by the weather. Within the wagon is a pregnant woman (Mildred Natwick) who is dying; despite their best efforts, Bob, Pete, and the Kid are only able to save the child. Her dying wish is for the three men to protect the boy and bring him to safety. While the prospect of three quirky outlaws trying to bring an infant to safety seems rather silly compared to Wayne and Fords’ other collaborations, the film shows that the child’s innocence is at stake. Collateral damage has never been a concern for Bob before, but seeing an innocent infant in danger forces him to reconsider his life’s work.While the woman’s death and childbirth are treated with gravity, 3 Godfather is a more humorous film compared to Ford’s other westerns. Wayne is often not given credit for his talents as a comedic actor, as he wouldn’t star in the western comedy McLintock! for another decade. Watching Bob, Pete, and William attempt to bathe, feed, and entertain the baby is immensely entertaining, as it’s clear that none of them have ever seriously considered fatherhood. Their lives as bandits are so exciting that the prospect of “settling down” never felt like a possibility. Although watching over the child initially seems like a burden, all three men discover that empathy has its own rewards.

‘3 Godfathers’ Uses Deliberately Slow Pacing

Ford is a favorite filmmaker of directors like Steven Spielberg because of the deceptive simplicity of his stories. 3 Godfathers is relatively light on action, saving the majority of its set pieces for the opening and closing moments. While the lack of forward momentum could have been a determinant of the film’s pacing, the straightforward story allows 3 Godfathers to put a greater focus on its characters. It’s entertaining to see how Bob, Pete, and William each draw from their own experiences as they figure out what they must do to ensure the infant’s help. While their disagreements over the best parenting practices (including one particularly amusing argument over when to bathe the child) occasionally spark arguments, the characters are never aggressive and cruel to each other. The positive depiction of masculinity has made 3 Godfathers age very well in comparison to other Westerns from the classic era.

The gradual pacing also allows Ford to focus on the gorgeous natural environments. A recurring hallmark within Wayne and Fords’ collaborations is their grand scope, and 3 Godfathers uses its vivid cinematography to show the characters’ changing perspective. Bob, Pete, and William are only able to take note of the landscape’s natural beauty after they are forced to slow their pace to keep the infant safe; by moving at a slower rate, they finally recognize the natural beauty that has been in front of them the whole time. However, the gradual nature of their quest also exposes the characters to greater danger. While initially, the open Arizona desert feels exciting, the brutal weather constraints ultimately make their mission more strenuous. This is a piece of clever thematic storytelling on Ford’s part; he can suggest that the hectic lives that these men had been leading were unsustainable.Christmas Is an Important Part of ‘3 Godfathers’

3 Godfathers serves as a loose retelling of the Biblical story of the Three Wise Men and Jesus of Nazareth; Bob even quotes specific lines from scripture during the bandits’ first encounter with the dying mother, and the characters head for a town literally named “New Jerusalem.” While some faith-based movies risk being impenetrable to a non-Christian audience, the film doesn’t require knowledge of its religious allusions to be entertaining. If the references to Biblical verse are ignored, 3 Godfathers still works as an entertaining adventure story. The themes of kinship, humanity, and forgiveness are universal, and not exclusively bound to Christian beliefs.With its open-hearted characters and tactful humor, 3 Godfather proves that sentimentality isn’t a bad thing. The film has a positive message about the inner goodness within everyone, and how even the most unlikely of characters can become heroes. While the Western themes make 3 Godfather perfectly suited for fans of Wayne’s filmography, it’s the film’s faith in humanity that makes it a Christmas classic.

3 Godfathers is available to rent or purchase on Apple TV.

Entertainment

Best Western Movie of Each Decade – My Blog

The Western genre has evolved greatly through its more than a hundred years of existence. From silent tales of honor and dignity, through the iconic look of John Ford and the coolness of Clint Eastwood, all the way to the deconstruction of the genre, each decade has had its share of the genre. The first years of the 20th century saw the Western become part of Hollywood’s agenda, and from the ’40s to the early ’60s, the genre reached its “golden age.”

From the ’60s onward, a much-needed reinvention of ideas and conventions found the genre-shifting toward the present. A new generation of filmmakers gave Westerns their own twist, eventually spawning a variety of subgenres that have been explored all the way into the present. Contemporary works like The Keeping Room, Power of the Dog, or The Rider, where a female-led cast or non-traditional masculinity is at the forefront of the movie, respectively, show just how exciting and diverse the genre has become.

With a rich past, an exciting present, and a bright future, Westerns are more alive than ever. These are the best of each decade, ever since the dawn of the twentieth century.Updated January 14, 2024: This article has been updated with additional Westerns from the current decade, along with where to stream them.The Great Train Robbery (1903)

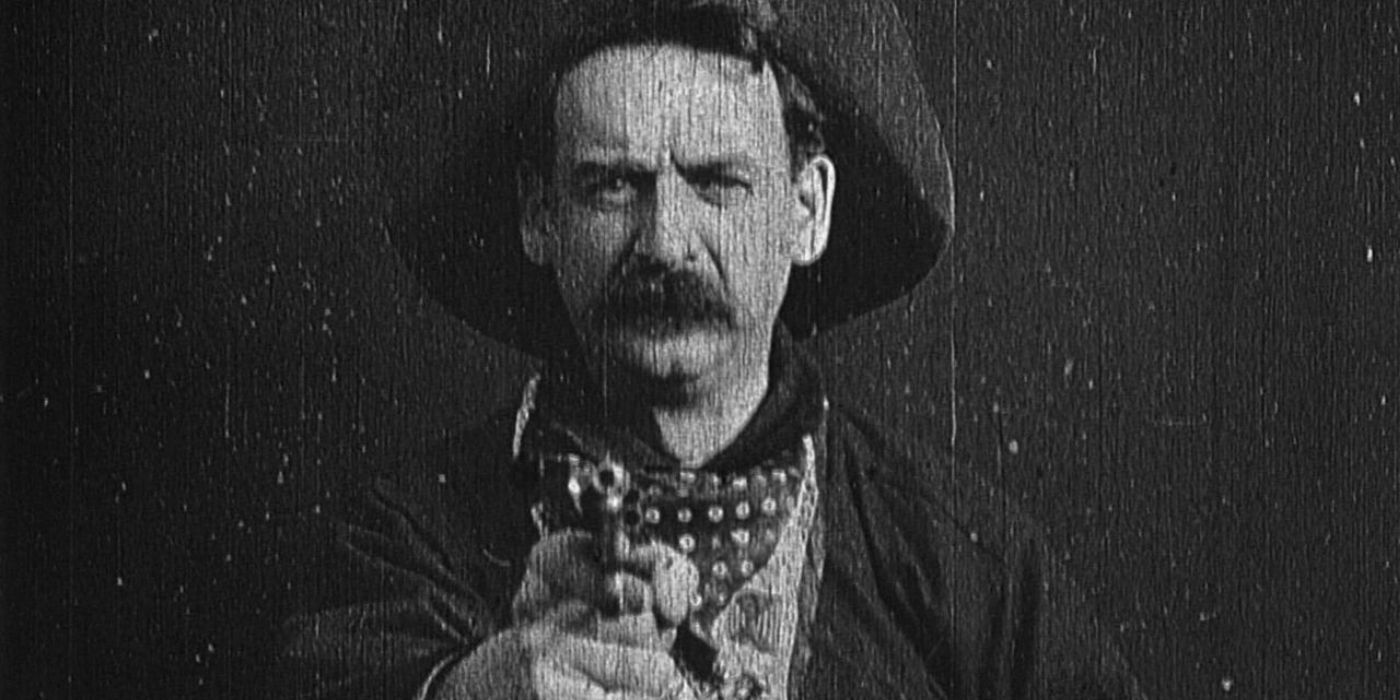

One of the first-ever Westerns was made when the myth of the Old West wasn’t even that ingrained into society. The stories and legends of the American Frontier still managed to find their way into the American public through word of mouth and pocket novels, and so it arrived all the way to the East Coast in the mind of film pioneer Edwin S. Porter. The 12-minute silent film conveyed the story of a group of outlaws who plan to rob a train in the southwest. The gang not only succeeds in taking off with the look but also terrorize the passengers on board.

The Great Train Robbery Is The True Pioneering WesternThe creator of over 250 films between 1901 and 1908, Edwin S. Porter, made this crisp short film a thrilling ride for its time. With breakneck pacing, innovative cinematography techniques, and enormous potential, The Great Train Robbery became even more iconic because of its final shot consisting of the lead bandit taking aim at the audience, bringing viewers into his world of thrill and danger. In a way, Porter’s creative storytelling laid the framework for structuring the narrative for a Western. Martin Scorsese paid homage nearly 90 years later, ending Goodfellas similarly. Stream on KanopyHell’s Hinges (1916)

Before Clint Eastwood, even before John Wayne, there was William S. Hart. This legend from cinema’s silent age was the first superstar of Westerns, who typically embodied characters who were honorable and morally incorruptible. In the one-hour film Hell’s Hinges, he plays a dangerous gunman named Blaze Tracy, who is commissioned by the local bartender and his accomplices to run out of town a recently-arrived priest and his sister. In turn, he is won by their sincerity and stands in their defense.

Tortured Gunslinger And His Silent RedemptionDirected by Charles Swickard, Hell’s Hinges came into movies just when the Western genre had begun to bloom. With Hart playing the intense anti-hero and bringing his Shakespearean to every scene, it was impossible for the film not to stand out. His conflicted knack for justice fuels every pulse-pounding cinematic shootout. While the drama and suspense were heavy and artistic enough, the complex character study hooked audiences. Hell’s Hinges proved that Westerns could also be a sophisticated form of entertainment. Stream on The Roku ChannelTumbleweeds (1925)

Speaking of William S. Hart, the old master continued with this underrated 1925 film, which was also his last. Self-financed, produced by and starring him, Tumbleweeds depicts the Cherokee Strip land rush of 1893. The movie sees his character, Don Carver, lighting up for one last adventure. This time however, he simply wanted to buy some land and settle down with Molly Lassiter, whom he fell in love with at first sight. Marked by warmth and wisdom, the movie celebrated Hart’s indelible impact on turning westerns into vehicles for storytelling.

Tumbleweeds Is An Iconic Cowboy’s Final RideIn 1939, Tumbleweeds was revived by Astor Pictures and enjoyed another theatrical run. The film now began with an eight-minute monologue by William S. Hart in which he reflected on the Old West and his heyday. This was the only time audiences ever heard his voice, which is much more moving when put in the context that Tumbleweeds was his last ever film. By the mid-’20s, however, audiences were no longer interested in Hart’s brand of westerns, for which he was subsequently dropped by Paramount. Despite its critical praise, the film performed mildly at the box office and has been largely forgotten, which is a huge shame. Stream on Fubo TVStagecoach (1939)Despite being director John Ford’s first Western in over a decade, Stagecoach is to this day one of the most important Westerns ever made. It redefined the genre by being more than what it promises. Its profound narrative is really an allegory for the formation of The United States. The plot follows a group of people traveling on a stagecoach as they learn from one another through the journey and its perils. Being locked in a tense and claustrophobic environment really sets the stage for massive character studies. One of John Ford and John Wayne’s most enduring classics provides fantastic insight into social classes, prejudice, and change.

The Timeless Appeal of Ford-Wayne CollaborationStagecoach is a must-watch for any enthusiast of the Western genre because of its ability to keep creeping forward toward a greater sense of understanding. Ford sharpens his genius for layered narratives and riveting action set pieces to comment on a society that is ever-evolving. As for John Wayne, the actor comes into his own alongside veterans like Thomas Mitchell, Claire Trevor, John Carradine, and more. From the landscape to the sparse dialogue, the film is simply an hour-and-a-half-long masterpiece of the genre. Stream on Prime VideoMy Darling Clementine (1946)My Darling Clementine is one of the few times when John Ford and Henry Fonda came together to create an enduring classic. The film, which follows the legendary Western character Wyatt Earp and his brothers, is a beautifully romantic revenge story. Arriving at the town of Tombstone for a night of rest, Earp wakes up and discovers that one of his brothers has died and their cattle are stolen. Despite the urgency of the plot, the Western remains unique in the legendary director’s filmography for its patient pacing and tone. It’s a quiet masterpiece that often gets overlooked compared to the many that Ford has made.Why My Darling Clementine Is A Cultural TouchstoneFew director-actor combos were as successful as John Ford and John Wayne. However, people often forget they had other classics aside from their Westerns, and people often forget, as well, that Ford was just as brilliant in his works as Henry Fonda. In the 1946 film, the director found boundary-pushing heights by unlocking a softer side to the genre. Its subtle and soulful amalgamation of romance, violence, and justice in the untamed West reminds you of the tenderness that lies beneath the rough. Fonda, as usual, imbues his character with both immense grit and vulnerability. Rent on Apple TVThe Searchers (1956)The Searchers find Ford and Wayne at the top of their capacities, creating a morally ambiguous Western whose influence is felt up to this very day. It concerns a Civil War veteran who, for years, searches for his abducted niece while being accompanied by his adopted nephew. For its underlying narratives tackling race relations, prejudice, and moral dilemmas, and its iconic use of the audiovisual language specific to the medium of film marked a before and after in not only Westerns but in cinema itself.

The Frontier’s Edge Has Never Been More GloriousAs long as there have been Academy Awards, there have been major snubs. The 29th edition of the Oscars left out, without a single nomination, one of the most lauded and influential motion pictures in film history. Only later has its impact been recognized, with the American Film Institute naming the film as “greatest American Western.” Like few other films before or since The Searchers radically changed the game by showcasing America’s darkest aspects. From the identity crises to shifting social sands, its bleak interpretation of what’s to come in the future poses more questions and concerns than answers and comfort. Rent on Apple TVOnce Upon a Time in the West (1968)As times and film changed, the 1960s saw an exhaustion of the traditional formula of Westerns. A new way of using the genre came to be through the brilliant mind of Sergio Leone. His reinvention of the genre came to be known as “spaghetti westerns” and was very different from your traditional tales of the Old West. Once Upon a Time in the West follows the story of a mysterious harmonica-playing gunslinger who becomes the only person to protect Jill McBain’s life and newly inherited land from bandits scheming to seize it from her.

Leone’s Slow-Paced Western Is A Blessing To CinemaLeone’s ‘Dollars Trilogy’ with Clint Eastwood began to cement his legacy, and by 1968, he created the definite western of the ’60s. Framed against the epic scope of America’s Western expansion, its surprising plot twists and intricate details make the film high art. Once Upon a Time in the West is an all-star affair featuring Henry Fonda unusually cast as a villain and a magnificent story made with the help of, surprisingly, Dario Argento and Bernardo Bertolucci. With Ennio Morricone’s humble score pulsing through like a heartbeat, the film is an homage to the genre as well as a step forward in it and has some of the best performances in any Western film. Rent on Apple TV

McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971)

Described by director Robert Altman himself as an “anti-western,” McCabe and Mrs. Miller is a profoundly original and modern take on the genre. Witty, funny, romantic, and heartbreaking, the film is part of Altman’s great run in the early ’70s and uses the West as an excuse to talk about America itself. Set in the 19th-century Pacific Northwest, the plot follows a gambler and a prostitute who fall in love and do business together. Their initial success, though, is fatally doomed.How McCabe & Mrs. Miller Subverts Clichés Within The GenreAltman strips all conventions bare here. He recasts the West as an anti-romantic fairy tale and gives us a moldy and muddy picture of the frontier village. The period setting and the epic production value make even its bleakest aspects seem realistic and accurate. Warren Beatty and Julie Christie’s soulful leads are so fascinating that you cannot help but root for them to end up together. That said, the film’s iconic approach, landmark setting of snowy Vancouver, and a deeply depressing score by Leonard Cohen set it apart from any other Western ever made. Rent on Apple TVHeaven’s Gate (1980)Directed by Michael Cimino, Heaven’s Gate tells the story of County Sheriff James Averill, who is tasked with protecting immigrants in 19th-century Wyoming. But as change progresses and political tensions between the two parties rise, he finds himself embroiled in a game of betrayal and violence. Nate Champion, the man appointed by Averill to keep the stockmen in check, commits a crime and ends up in a feud with the Marshalls. The film follows a dispute between poor immigrants, wealthy cattle farmers, and the woman they love.Heaven’s Gate Was Too Ahead Of Its TimeAt its time, Heaven’s Gate was a commercial and critical flop, which is what happens when an epic film soars too close to the sun. Today, it’s seen as one of the most misunderstood films ever, and a masterpiece in its own right. The infamous production, which had numerous setbacks, influenced critics way before the film was in theaters and is said to have helped destroy the auteur approach of New Hollywood that had developed in the ’60s and ’70s. The new director’s cut of the film gave Heaven’s Gate a new place in history, and rightfully so; it proves to be arguably the most imaginative and accomplished western of its decade. Stream on Prime VideoUnforgiven (1992)

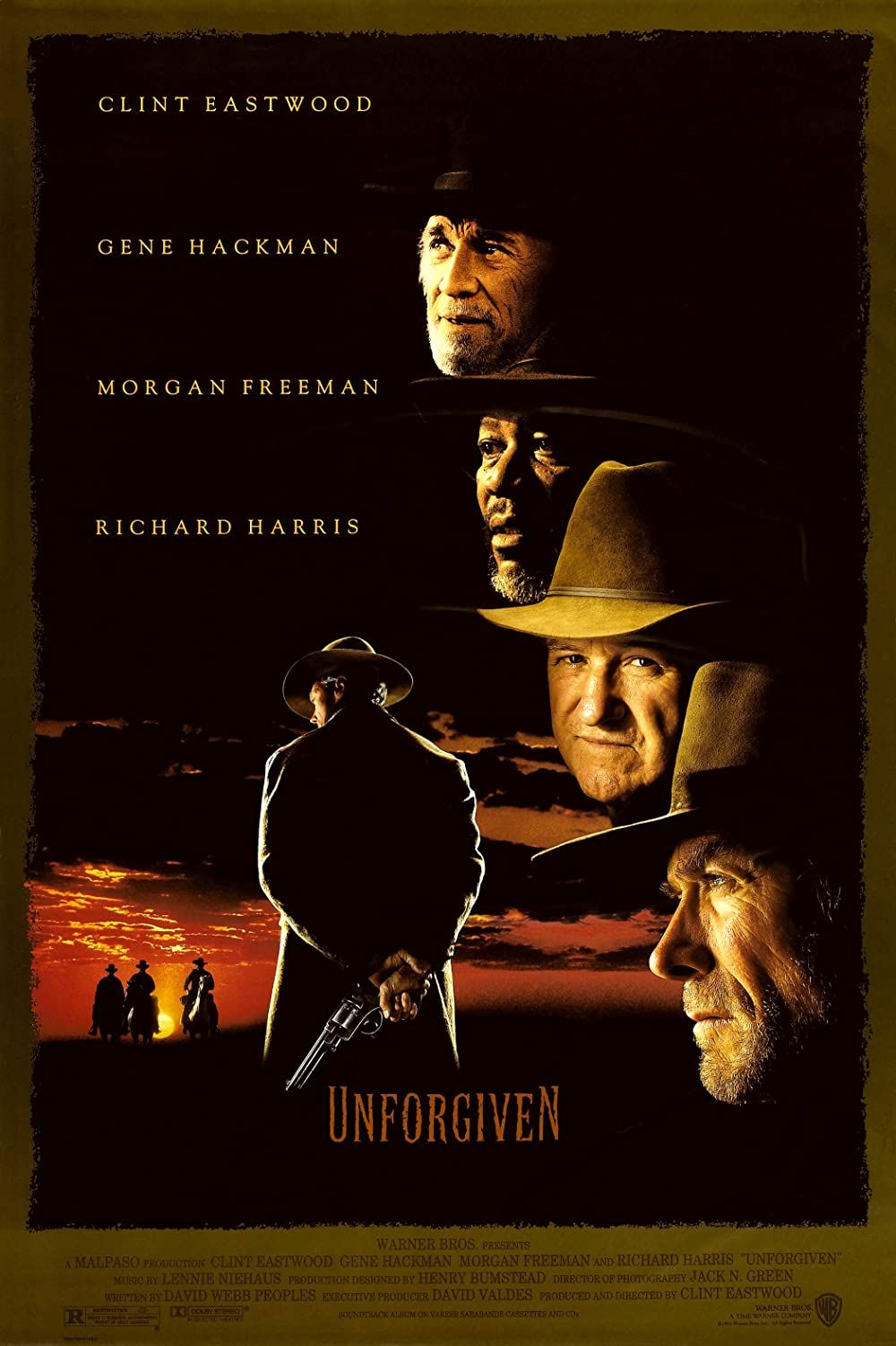

Unforgiven (1992)

Release Date August 7, 1992Director Clint EastwoodCast Clint Eastwood , Gene Hackman , Morgan Freeman , Richard Harris , Jaimz WoolvettRating RMain Genre Western

Charting off into the ‘90s, we have Unforgiven. The film is directed by Clint Eastwood, who also stars in it. Fun fact: Eastwood had been offered the Unforgiven script since the early ’80s but held onto it for a decade until he felt he was old enough to play the lead. He plays William Munny, a former gunslinger and aging outlaw who gave up on his life of violence and remorseless killing after marriage and turned to fighting instead. He takes one last job to earn money for his family and is soon embroiled in a sadistic showdown.Unforgiven Is The Story Of A Man With A Regrettable PastThe ‘90s were a golden period in Eastwood’s magnificent life when he allowed themes of the Old West to meet their twilight. The result was patient, morally complex, and mature Western films that marked Eastwood’s long relationship with the genre. Along with notable stars like Gene Hackman, Richard Harris, and Morgan Freeman, he crafted an achingly beautiful portrait of the toll violence takes on human life. His poised direction and acting are a poetic declaration of the genre’s influence on him and vice versa. Unforgiven still remains a touchstone of the genre, and the idea of an old retired gunslinger has been the basis for many popular stories, including Logan. Rent on Apple TVNo Country For Old Men (2007)

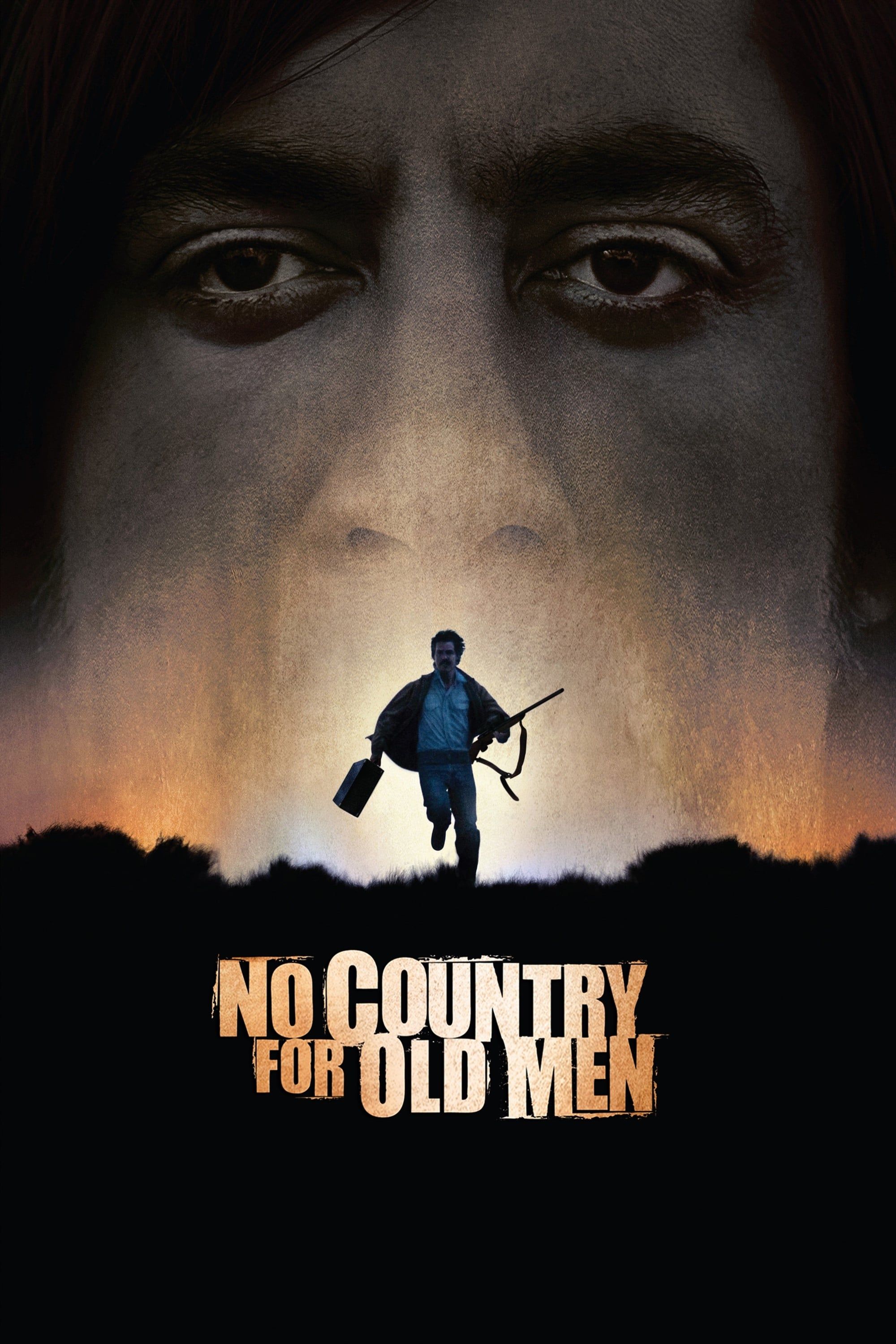

No Country for Old Men

Release Date November 8, 2007Director Ethan Coen , Joel CoenCast Tommy Lee Jones , Javier Bardem , Josh Brolin , Woody Harrelson , Kelly Macdonald , Garret DillahuntRating RMain Genre Crime

The Coen Brothers have often played around the Western genre, from the sounds of The Big Lebowski to their remake of True Grit in 2010, but their definitive take on the genre is their 20007 film, No Country For Old Men. This Academy Award-winning masterpiece is led by career-defining performances from Javier Bardem, Josh Brolin, and Tommy Lee Jones. The movie is a dark story about the death of the old West and the birth of a much darker new one; it follows the lives of various characters as one of them comes upon a bag full of drug money, a catalyst for the madness that follows.No Country For Old Men Is A Neo-Western That Flows Like PoetryThe film is based on Cormac McCarthy’s novel of the same name, the narrative inhabiting the essence of Western conventions yet steering away from them in a fascinating way. Javier Bardem is malicious as Anton Chugar, playing an ever-changing game with Josh Brolin’s Moss. The movie is set against the backdrop of harsh landscapes, which makes for a complex and haunting mood. For its grim and unforgiving portrayal of modern border life, it surely is one of the most realistic modern Westerns and helped kick off a new-wave of Neo-Westerns for films like Hell or High Water, Logan, and Wind River. Stream on ShowtimeThe Rider (2017)Westerns’ ongoing deconstruction is partly thanks to the diversity of filmmakers tackling it. This has allowed for cinematic joy that is The Rider to exist. This ultra-low-budget project follows Brady Blackburn, a once-promising rodeo star, as he adapts to his life as a horse trainer after his skull gets crushed and he is unable to return to riding. Directed by Chloe Zhao, who would later win an Academy Award for Best Director for Nomadland and get a big studio film with Marvel’s Eternals, the film is a gorgeous journey of acceptance. The Rider presents a very different approach to masculinity than the one traditionally found in Westerns.Why The Rider Is A Tragic And Unconventional MasterpieceOne of the most poignant Westerns to date, The Rider creates a raw and intimate portrait of a man’s identity and his progress as he heals from a jarring life event. The film is led by non-professional actors, with breakout star Brady Jandreau delivering a grounded and graceful performance as the male lead. Sparse in dialogue, rich in experience, and driven by emotion, the movie is a contemporary classic that makes the Western genre more accessible to the new generation. It helped define Zhao as one of the best directors working today and alongside the release of Wind River and Logan that same year, 2017 was a great year for Westerns. Rent on Apple TVKillers of the Flower Moon (2023)

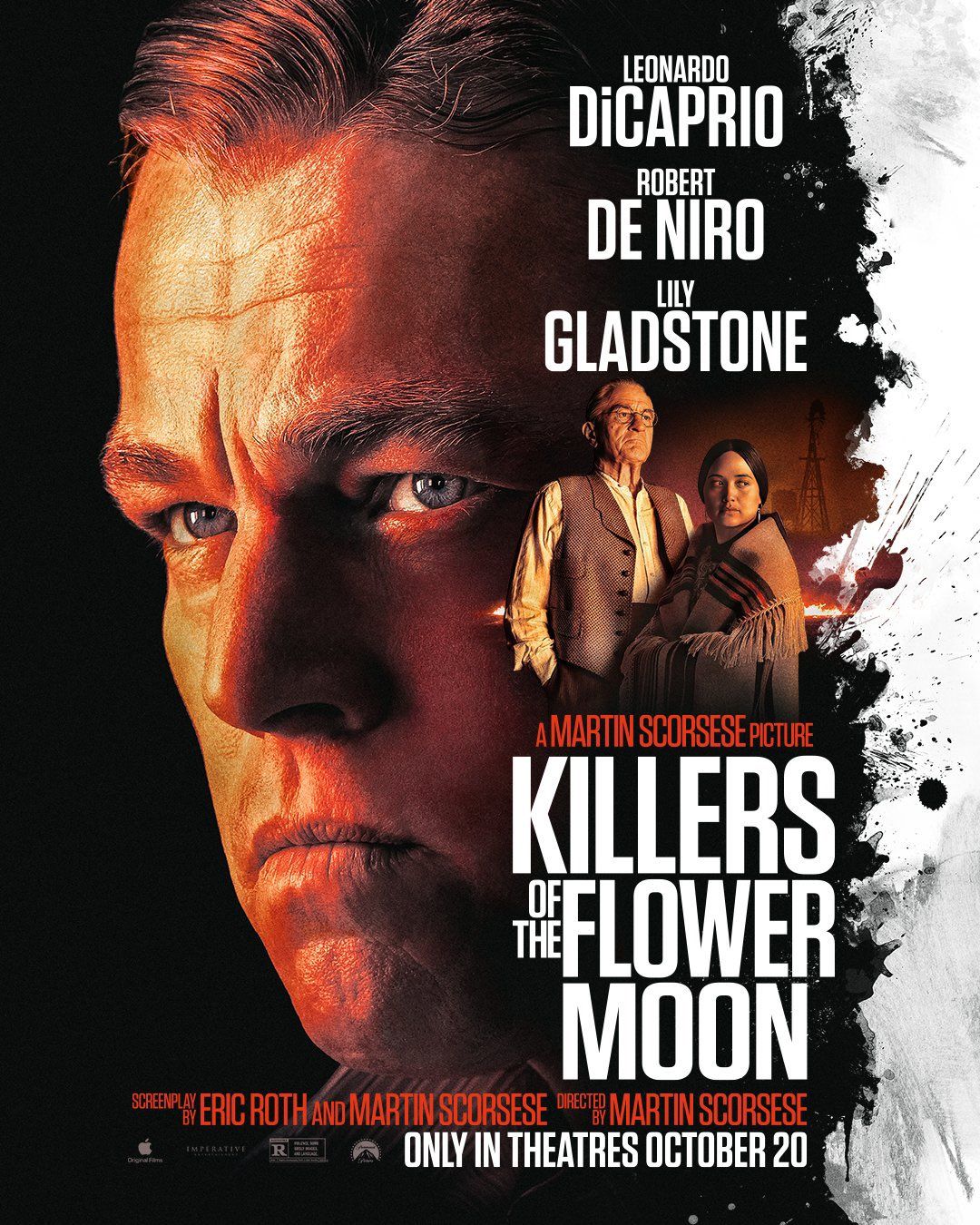

Killers of the Flower Moon

Release Date October 20, 2023Director Martin ScorseseCast Leonardo DiCaprio , Robert De Niro , Lily Gladstone , Jesse Plemons , John Lithgow , Brendan FraserRating RMain Genre Drama

Quietly examining America’s relationship with those people who turned it into the nation it is today, Killers of the Flower Moon is director Martin Scorsese’s latest epic. It adapts David Grann’s non-fiction book and depicts the true story of the Osage Indian murders in 1920s Oklahoma. The Osage people had become rich after oil was discovered beneath their land, but the darkness only cast upon their lives when Ernest Burkhart returned from World War I and married Mollie Kyle, an Osage woman with headlights, to get close to her family’s money.Emotional, Brutal, and MagnificentRobert De Niro, Leonardo DiCaprio, and Lily Gladstone lead a talented ensemble of layered and complex characters. Scorsese channels the same visionary storytelling he’s known for to shed light not only on a forgotten piece of American history and deconstruct the Western genre but also highlight the plight of the Native American people, a community often villanized in early Westerns like The Searchers and Stagecoach. Killers of the Flower Moon paints a horrific portrait of an unsettling time when criminal acts of injustice were shaping the country. From its attention to factual details to the pulsating score, this thought-provoking epic is destined to join the ranks of the most impactful films in the Western genre. Stream on Apple TV

Entertainment

The “pansy” role that “embarrassed” John Wayne – My Blog

While the likes of True Grit, The Searchers and Rio Bravo saw Wayne deliver his highly masculine take on the acting profession, smoking and fighting his way through scenes early in his career, he also had to take on some projects in order to get his career up off the ground in heading for stardom.Following the box office failure of The Big Trail, Wayne had to star in a number of B-movies throughout the 1930s until he starred in John Ford’s Stagecoach. One such instance came in 1933 with the pre-Code western musical film Riders of Destiny, in which he starred as the second iteration of the singing cowboy Singin’ Sandy Saunders.Ken Maynard had already portrayed Saunders in the 1929 film The Wagon Master, and while Wayne took on the role, it was not one that he would hold close to his heart for the remainder of his life. In fact, Wayne actually felt embarrassed over his performance, particularly because he did not want to be associated with singing characters that he perceived as weak.Writer Michael Munn wrote in John Wayne: The Man Behind the Myth, “He started at Lone Star as Singin’ Sandy Saunders, the singing cowboy, in Riders of Destiny. It was something that would haunt Wayne for the rest of his life as the subject of his singing would often be brought up.”“I was just so fucking embarrassed by it all,” Wayne once said of his performance as the singing cowboy. “Strumming a guitar I couldn’t play and miming to a voice which was provided by a real singer made me feel like a fucking pansy. After that experience, I refused to be Singin’ Sandy again.”It’s clear that Wayne’s singing voice as Singin’ Sandy Saunders in Riders of Destiny was not anything like his actual speaking voice; that’s because it was provided by Bill Bradbury, the son of the film’s director Robert N. Bradbury. Still, the film’s reception led fans of Wayne to ask him to sing, a request that he simply refused each time.Check out the full version of Riders of Destiny below.

Trending

-

Entertainment7 months ago

Entertainment7 months agoJohn Wayne’s son speaks on military service, Hollywood life and his dad, ‘The Duke’ – My Blog

-

Entertainment8 months ago

Entertainment8 months ago40 Legendary John Wayne Quotes – My Blog

-

Entertainment8 months ago

Entertainment8 months agoNew biography reveals the real John Wayne – My Blog

-

Entertainment10 months ago

Entertainment10 months agoWhy one POPULAR ACTOR was FIRED from THE SONS OF KATIE ELDER and lost his career as a result! – Old western – My Blog

-

Entertainment7 months ago

Entertainment7 months agoHow Maureen O’Hara Broke Her Hand During Iconic Scene With John Wayne – My Blog

-

Entertainment8 months ago

Entertainment8 months agoRio Lobo (1970) marked the last collaboration between John Wayne and Howard Hawks. – My Blog

-

Entertainment8 months ago

Entertainment8 months agoDid John Wayne really have a good time filming 1972’s The Cowboys? – My Blog

-

Entertainment7 months ago

Entertainment7 months agoJohn Wayne and the ‘Bonanza’ Cast Appeared in This Epic Coors Light Commercial – My Blog